The emergency services in Norway are primarily meant to cover the population’s need for immediate medical aid at any time of the day or night (1). Immediate aid means «the first aid the medical services or a health worker is obliged to provide without any unavoidable delay when the available information indicates urgent necessity» (2). A substantial part of the work done by emergency services hardly complies with this strict definition. The patients’ and doctors’ understanding of what is reasonable to expect from the service also varies with local conditions.

There has been a need for at more systematic appraisal of the use of emergency clinics. Evaluation of the Regular General Practitioner (RGP) Scheme has given us new insight. The number of emergency consultations and home visits seems to vary considerably. The sum of consultations and home visits in the same geographical area can for example vary by a factor of two (3). The relationship between home visits and emergency consultations varies from 1 : 1 in 15 municipalities in West Agder to 1 : 13 in Skien (4, 5). More emergency consultations and home visits occur in the smaller municipalities (3 - 5), indicating that municipality size is also a factor to consider.

In Skien and Siljan emergency district, patients’ attitudes to the emergency service were found to depend on where their regular general practitioner (GP) was working (5). In Bergen, three out of four patients had made no attempt to contact their regular GP before visiting the emergency clinic (6). But about half of them would not mind waiting a day, had they been guaranteed an appointment with their doctor. 84 % knew who their regular GP was. In another survey, 43 % of the patients in Fredrikstad and 47 % of those in Tromsø had tried to contact their doctor during regular work hours on the day of their emergency consultation (7).

During our study in Stavanger (1989 - 2002), the emergency service was responsible for a population of about 110 000 patients. The emergency service is managed by regular GPs and by 1 - 2 permanently employed emergency doctors during regular work hours. In the evenings there are three doctors on duty, one of them doing home visits. One doctor alone covers the night. The emergency district has short distances and a good ambulance service. Patients can come directly to the emergency clinic, get registered and assigned priority and wait for their turn. The doctor or nurse on duty cannot give medical advice by telephone. This system creates queues unless there is overstaffing (8). If acute care is not required, the waiting time varies from about 30 minutes to several hours.

The aim of this study was to gain a better understanding of factors that affect the use of emergency services in a city. By describing and analysing changes in the frequency of emergency consultations in Stavanger from 1989 to 2002, we aimed to determine whether introduction of the RGP Scheme had influenced the use of emergency services. Our hypothesis was that organisation of general practice during regular work hours affects the number of consultations in the evening.

Material and methods

Stavanger’s emergency service has systematically recorded every contact made by day and night since 1986. We chose to use all recorded consultations and home visits from 4 pm to 11 pm on weekdays from 1989 to 2002. All figures are given per 1 000 inhabitants annually, based on the population at the start of the year. To assess a possible influence of the RGP Scheme, introduced 1 June 2001, we compared the rate of consultations for the first 17 months (June 2001 - October 2002) with a similar time span before this date (June 1999 - October 2000). Changes in the organisation of the emergency service and general practice during regular work hours are compared with changes in the frequency of emergency consultations. The most important changes in the period are shown in Table 1 and described in the results and discussion sections.

|

Table 1 Important changes in the emergency and primary health services in Stavanger from 1986 to 2002

|

|

Changed capacity

|

|

New provisions

|

6 fixed-salary general practitioner positions March 1994

|

|

4 fixed-salary general practitioner positions in 1997

|

|

6 new municipal contracts in January, 1 new contract in June 2001

|

|

|

|

New organisation

|

Transfer from fixed salary to municipal contract, 20 doctors, January 1998

|

|

|

|

Alternative service

|

Forus Casualty Clinic opened in 1998, open weekdays 4 pm - 8 pm with 4 - 5 emergency consultations an evening

|

|

|

|

Emergency clinic’s profile

|

|

New, attractive building

|

August 1998

|

|

Public information

|

Public information brochure May 1999

|

|

|

|

Implementation of the RGP Scheme

|

June 2001

|

We used the programme Confidence Interval Analysis (CIA), version 2.0 (9). Changes in the use of emergency services are given as absolute or relative increases or decreases in the number of emergency clinic consultations and home visits. Differences in consultation rates are given as difference between the number of consultations with 99 % confidence intervals.

Results

Figure 1 shows that consultations and home visits in the evening (4 pm to 11 pm) rose each year from 1989 to 1997. There was a steady decrease from 1997 to 2002. Conversely, there were 227 consultations and home visits per 1 000 inhabitants in 2000. This was lower that the annual rate of 233/1 000 for the year 1989 and much lower that for the peak year of 1997 (278/1 000).

We found an absolute increase in the rate of consultations and home visits of 4.6 % (99 % CI: 4.1 - 5.1) from 1987 to 1997, which corresponds to a 20 % relative increase. From 1997 to 2002 there was a steady absolute decrease of 5.3 % (CI: 4.8 - 5.7), or a 19 % relative reduction. The greatest change from one year to the next was seen from 1997 to 1998, when there was an absolute reduction of consultations and home visits of 2.4 % (CI: 1.9 - 2.9).

The proportion of home visits to emergency consultations changed during the period assessed. Whereas home visits constituted 25 % of all GP consultations in 1989, the corresponding number for 2002 was 11 %.

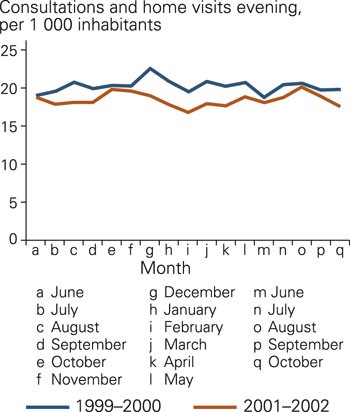

The rate of consultations and home visits during the first 17 months after the implementation of the RGP Scheme (June 2001 - October 2002) showed an absolute decrease of 2.2 % (99 % CI: 1.7 - 2.6) (corresponding to a 10 % relative decrease), compared to the same period before the Scheme was introduced (June 1999 - October 2000). Figure 2 gives the monthly rates and shows that there were generally fewer emergency contacts with a doctor after introduction of the RGP Scheme.

Consultations and home visits in the evening (4 pm - 11 pm) per 1 000 inhabitants in monthly rates in Stavanger before and after implementation of the RGP Scheme

Table 1 presents a comparison between organisational changes and changes in the emergency consultation rates. The creation of six new doctor practices in March 1994 did not lead to fewer emergency consultations that year. The large decrease in emergency consultations after 1997 coincided with the transfer of 20 doctors from a fixed salary to contract work. The opening of a very attractive emergency clinic in August 1998 brought no increase in the number of consultations. After 1999, the implementation of the RGP Scheme and the creation of seven new GP practices were the most important events. These coincided with a steady decrease in the number of emergency consultations. In the same period, a private casualty clinic opened in Forus with a modest evening consultation service.

Discussion

We found that use of the emergency service in Stavanger changed considerably from 1989 to 2002. The changes coincided primarily with considerable changes in the GP capacity during work hours. A moderate increase in the work capacity of a large number of doctors seems to have had a greater impact than an increase in the number of doctors.

The large number of residents in the emergency district studied makes us confident that the changes in the use of emergency services do not represent random fluctuations. The same applies to our use of a 99 % confidence interval. The tendencies in our data are also clear and consistent from year to year. The creation of many new jobs for medical doctors at the same time and the introduction of an organisational change affecting a large number of doctors, give a good basis for our evaluations. An approximation is that one in three emergency service doctors were normally working in a hospital. This figure has remained more or less stable for many years. Moreover, doctors on duty have not had time to record much of the work done by the emergency service.

The setting up of a completely private medical centre in November 1998, Forus Casualty Clinic, creates some uncertainty as it may have reduced the number of emergency consultations by 3 - 5 patients per evening and a little less after the implementation of the RGP Scheme (A. Kaisen, personal communication). Forus Casualty Clinic may account for some of the reduction in emergency consultations, but not all of the annual decrease from 1997 to 2002.

Both structural and conceptual factors can affect the sharing of the workload between GPs and emergency doctors on duty. The structural factors are related to the actual capacity the regular GP and the emergency service has to treat patients in need of various types of help. Conceptual factors comprise what the population and amongst the doctors consider to be a sensible distribution of workload.

Structural factors

There were no structural changes of the emergency service during the study period, which implies that the emergency service and the systems for professional evaluation and sifting of patient calls have been the same. The steady increase of emergency consultations from 1989 to 1997, can be explained by an increasing number of patients who did not manage to get through to a GP during work hours and needed to find other solutions. An increase in the number of GPs only had a short-term or no effect in this connection (Figure 1).

Twenty doctors transferred from a fixed salary to a contract agreement with their municipality from January 1998. The number of emergency consultations in the evening was 8.7 % lower in 1998 than in 1997. This was the most marked decrease in a single year. Bjørndal and colleagues found that doctors employed by municipalities and doctors on contracts work in a similar way, but that doctors on contracts have more consultations during work hours (10). The change in the way of working has probably been a stimulus for doctors to make themselves more available during daytime and to work more effectively.

The health service was strengthened by establishing seven new doctor practices when the RGP Scheme was implemented. Patients were immediately distributed between the new and established doctors, so the established doctors had a smaller workload after the implementation of the Scheme. The doctors were therefore better able to meet the acute care needs of their own list patients. We believe this to be the most important reason for 10 % fewer emergency consultations during the first 17 months after the implementation of the RGP Scheme.

Implementation of both the contract and the RGP schemes were accompanied by a moderate but clear increase in the capacity of a large number of doctors. This type of change appears to have larger consequences than an increase in the number of doctors.

A consequence of this will be that if the amount of work associated with a patient list of a certain length increases over time, the regular GPs will be less able to offer acute care during daytime. An increase in emergency clinic consultations may therefore be a signal of an increasing workload for the regular GPs.

Conceptual factors

We need a greater understanding in this area. The emergency service is dependent on an alliance between the population and the doctors. This involves a mutual understanding of what the emergency service is for. Small changes in attitude can bear much fruit over time. From the patient’s point of view the question is, «where can I get help for this problem?» From the GP the question is, «what is my responsibility during work hours and how can I maintain it?»

The number of emergency service consultations decreased steadily from 2000 and throughout the period assessed. One explanation may be that the immanent choice of a regular GP raised both doctors’ and patients’ awareness of the need to be committed to one doctor. This may have influenced the behaviour of both parties. From Skien and Siljan we know that the availability of doctors varies considerably (5). We also know that about half of the patients who consulted the emergency clinic in Bergen, Fredrikstad and Tromsø would rather have used their regular GP (6, 7).

Conclusion

Emergency services are used for more than acute care, as indicated by 20 % annual variation in the number of consultations. Reduction of out-of-hours emergency work is best obtained by providing a well-organised general practice during daytime. Emphasis of the emergency service as a provider of acute care, will probably have stronger clout when patients’ needs are met by their own doctor.