Rehabilitation medicine includes all aspects of human life and requires goal-directed planning, active user participation and a multidisciplinary approach (1). We are facing a great challenge concerning services offered to one of our country’s largest patient groups - people with chronic musculoskeletal pain where diagnostic imaging and blood tests fail to reveal a clear organic cause. The area is further confused by lack of consensus on the nature of the pain, which has caused a profusion of names for the condition e.g. «unspecified psychosomatic disease», «chronic widespread pain», «chronic muscle pain syndrome», «fibromyalgia», «soft tissue rheumatism», «chronic unspecific low back pain», «myalgia» or the much used «myofascial pain» (2) (box 1).

Box 1

Myofascial pain is the same as muscle pain. The pain most probably originates from the myofascial trigger point, a localized contraction knot at the nerve-muscle junction. It causes a palpable band of muscle fibres, limited range of movement, referred pain and pressure tenderness. The patient perceives that the muscle is tight, painful and weak and that it is more easily fatigued.

Chronic unspecific low back pain is often diagnostically distinguished from the other conditions, a fact that seems to be based on tradition rather than organic evidence. The cause of low back pain is most often unknown (3) and Deyo has claimed that 85 % of the patients lack organic correlates for their back pain (4). Moreover, most low back pain patients also experience more widespread pain, and the tendency for the pain to spread increases with a longer symptom duration (5).

The prognostic factors of low back pain (so called yellow flags) more or less overlap with the risk factors for developing fibromyalgia (6, 7). Whereas the prevalence of pain only in the low back is relatively low, chronic low back pain concomitant with other musculoskeletal pain occurs as frequently as fibromyalgia, i.e. circa 6 - 7 % (5, 8, 9). Only a minority of the patients that meet the American College of Rheumatology 1990 (ACR-90) diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia are actually given that diagnosis in Norway (8, 10) (fig 1). This is a paradox, as an established diagnosis with information about the nature of the syndrome has a positive prognostic effect. One may wonder whether insecurity about what causes their pain and the lack of adequate rehabilitation possibilities that many patients face, contribute to Norway being number one in Europe with respect to chronic pain. Our prevalence is 30 % compared to a European average of 19 % (11).

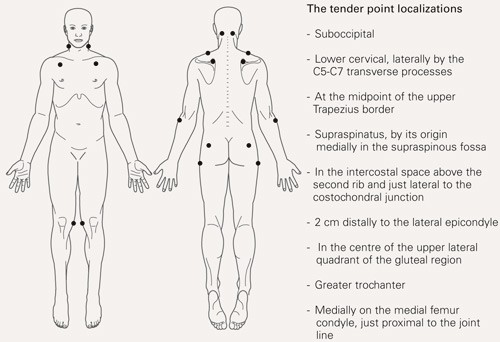

The American College of Rheumatology 1990 diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia (10). Widespread pain, i.e. pain in at least three quadrants of the body plus in the midline, of at least three months duration, together with pressure tenderness revealed by a perception of pain in at least 11 of 18 anatomically defined tender points (nine bilateral) when a finger is pressed with up to a 4 kg pressure on each point

Insufficient knowledge of the literature on diagnostics and treatment of myofascial pain contributes to uncertainty among health professionals when conventional examination shows «nothing wrong». In spite of the availability of evidence-based guidelines, patients meet a lack of consensus on treatment strategy. Many feel they are neither believed nor cared for and despair as health professionals do not manage to find the cause of their pain (12). This may advance negative thoughts and feelings, doctor shopping, and patients trying out conventional and/or complimentary treatments that are often expensive and without lasting effects (13). As long as the pain represents a threat, it functions as a warning signal, and will be uppermost in the patient’s mind. One instinctively avoids everything that might enhance the pain, which eventually leads to a dysfunctional pattern of movement and behaviour that unintentionally prolongs and increases the pain. The end result is often a passive, pain avoidance behaviour with secondary problems such as lack of fitness, depression and isolation.

Musculoskeletal pain is the most frequent reason for GP consultations, sick leave and disability pension in Norway (14). There is small curative value in offering patients passivity through a label of disease and economic compensation (15). Much could have been gained by offering proper rehabilitation to a greater extent and at an earlier stage. The number of treatments attempted before a patient is offered rehabilitation largely predicts the recidivism frequency. For every 10th visit to a health care provider the probability of low back pain recurrence increases by 22 % (16).

A biopsychosocial model

The development of chronic pain is a dynamic process involving neurophysiological pain regulation mechanisms and learning, as well as cognitive, emotional and behavioural aspects (17). The condition therefore needs to be understood in a biopsychosocial context where biological and psychosocial factors play equal roles. Relevant biological elements may be myofascial pain, a sensitized nervous system and physical de-conditioning. But disturbed sleep, and cognitive and emotional elements such as strong concentration on negative thoughts and feelings (catastrophization), too much attention to bodily sensations (hypervigilance) and severe chronic distress, may also contribute to the sensitizing process. Moreover, all of these elements may sustain and strengthen each other in a series of vicious circles thus adding to further chronicization (6). Logically, this model of understanding would call for multidimensional rehabilitation aimed at each of the contributing elements. Such an approach has indeed been documented to have positive effects on fibromyalgia and chronic low back pain (7, 18).

In 2004 the American Pain Society set up a panel of experts to find evidence-based guidelines for treating fibromyalgia. After assessing 505 treatment studies, the panel concluded on the following effective measures: A definite diagnosis, information/education, cognitive behavioural therapy, aerobic fitness training, a low dose of a tricyclic antidepressant (administered in the evening), and multidimensional rehabilitation that combined information and/or cognitive therapy with physical exercise training. Multidimensional rehabilitation was the only treatment that consistently showed lasting positive effects in the follow-up period. The authors also pointed out that there was little or no evidence for using opiates, antiflogistics, steroids, benzodiazepines, chiropractice, manual therapy, massage, electrotherapy or ultrasound. However, these treatment options are much used for fibromyalgia in Norway. No studies are so far available on myofascial pain treatment in fibromyalgia (18).

In the evidence-based European guidelines for the management of chronic low back pain, diagnostic clarification is recommended to eliminate pathology in the spinal canal, nerve root affection and structural deformities. Prognostic factors should be mapped; i.e. work situation, psychological strain and depression, severity of pain and to what extent this hampers functional level, previous episodes of low back pain, exaggerated reporting of symptoms and the patient’s own expectations. Recommended therapeutic interventions comprise information, cognitive behavioural therapy, guided physical training, short-course treatment with antiflogistics or weak opiates, and multidimensional rehabilitation (7).

After medical examination, patients with chronic myofascial-based musculoskeletal pain should be offered multidimensional rehabilitation. The minimum requirement is obligatory physical exercise with information and/or cognitive therapy (18). But several of the following components may be combined to advantage:

Extensive information on the cause and nature of the pain to give the patient confidence and understanding of factors that can aggravate, perpetuate or alleviate the pain. This forms the basis for mutual understanding between patient and therapist, which is the prerequisite for success. One should rouse hope and motivation in the patient, who should be given a true possibility of active self-management.

Cognitive behavioural therapy that emphasizes how negative thoughts can promote emotional reactions and hypervigilance, which in turn may lead to dysfunctional behaviour and long-lasting or increased, pain (19). Awareness of one’s own patterns of thought and notions, and how emotions, pain and behaviour may change as the result of choosing an alternative model for understanding, contribute to a secure, actively coping and well-functioning patient.

Aerobic exercise training, which has a documented positive effect on work capacity, sense of well-being, surplus energy, pain and sleep (18, 20, 21).

If necessary, medication taken at need for pain relief and sleep improvement.

Depending on the situation of the individual patient, these services may be given ambulant through their regular GP or an outpatient clinic, or intensively through hospitalization.

The Jeløy Kurbad Rehabilitation Centre has offered multidimensional rehabilitation to hospitalized patients with chronic myofascial pain/fibromyalgia since March 2001. The programme is intensive and has many components. It is unique, because in addition to the components mentioned above, it also includes diagnostics and treatment of the patients’ myofascial pain. As an example of how multidimensional rehabilitation may be done, this programme is presented with results at discharge and 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Material and methods

All patients with a referral diagnosis of chronic pain syndrome or fibromyalgia that received treatment at the Rehabilitation Centre from March 2001 to June 2003, were included in this open-labelled, prospective intervention study. Thus, patients with ongoing insurance claims, applicants of life-long disability pension, and patients with a foreign background were not excluded. 200 patients, 191 women and 9 men, with a mean age of 47 years and widespread pain of 13 years duration (tab 1) were included. On arrival, they all showed signs of myofascial pain (2) and 167 also met the ACR-90 diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia (10) (fig 1).

|

Table 1 Demographic data at arrival (N=200)

|

|

Sex (women/men)

|

191/9

|

|

|

|

|

Age (years) - mean (SD; range)

|

47 (10; 22 - 79)

|

|

|

|

|

Symptom duration (years) - mean (SD; range)

|

13 (8; 1 - 38)

|

|

|

|

|

Education (years) - mean (SD; range)

|

12 (3; 7 - 21)

|

|

|

|

|

Marital status

|

|

|

|

Married/cohabiter

|

145

|

(73 %)

|

|

Divorced

|

31

|

(16 %)

|

|

Widow

|

8

|

(4 %)

|

|

Single

|

16

|

(8 %)

|

|

|

|

|

Occupational status

|

|

|

|

Actively employed

|

34

|

(17 %)

|

|

Full time

|

9

|

(5 %)

|

|

Part time

|

25

|

(13 %)

|

|

On sick leave

|

133

|

(67 %)

|

|

Full time

|

105

|

(53 %)

|

|

Part time

|

28

|

(14 %)

|

|

On disability pension

|

53

|

(27 %)

|

|

Full time

|

32

|

(16 %)

|

|

Part time

|

21

|

(11 %)

|

|

Home keeper/others

|

9

|

(5 %)

|

The patients completed a self-administered questionnaire on arrival, at discharge and at 6 and 12-month follow-up. Clinical tests were also made on arrival and at discharge. At discharge, neither doctor nor patient had access to the results recorded on arrival. In addition to demographic data the following information was recorded:

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) ratings of pain, fatigue, poor sleep and depression (0 = none, 100 = the worst imaginable) (22).

The Nottingham Health Profile (NHP), scale 1, where the subscales for pain, energy, sleep and emotions were used as a control for the VAS results (score 0 - 100, 100 being the worst) (23).

The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), which maps status and measures changes in fibromyalgia patients. It includes the ability to perform activities of daily living, overall well-being, vocational status and seven VAS scales for symptom intensity (0 - 100, 100 being the worst). A Norwegian translation was made from the English (24) and Swedish (25) versions.

The patients’ experience of global subjective improvement (as compared to their situation on arrival) was recorded on a 5-step verbal rating scale at discharge and 6 and 12-month follow-up.

Experienced change in quality of life (as compared to the situation on arrival) was recorded on a 5-step verbal rating scale at 6 and 12-month follow-up.

Physical activity level due to exercise frequency, intensity and duration, was recorded at 6 and 12-month follow-up.

The following clinical tests were performed on arrival and at discharge:

Pressure tenderness, expressed as number of painful ACR-90 tender points, was recorded by the patient’s physician. It was also recorded whether or not the ACR-90 diagnostic criteria were met (10) (fig 1).

Work capacity was measured by a cycle ergometer test with an initial load of 50 W. The load was increased by 25 watts every third minute and the patients cycled for as long as they were able or willing to. Work capacity was expressed as the relationship between the maximum 3 min work load and corresponding heart rate (21).

The rehabilitation programme

The programme routinely treated 14 patients at a time with a circulating admission and discharge of three to four patients every week. They completed a 4-week standardized multidimensional rehabilitation programme in accordance with evidence-based guidelines, and aimed at the main biopsychosocial elements of their syndrome. These include: Social problems, myofascial pain, a sensitized nervous system, physical de-conditioning, poor sleep, distress and negative thoughts and feelings (6). The goal was to create confident and actively coping patients with increased insight and hope, motivated for making changes after discharge. The daily programme is given in table 2. It comprised both physical-medical and psychosocial components:

|

Table 2 Template for the pain patients’ plan for the day in the multidimensional rehabilitation programme at Jeløy Kurbad Rehabilitation Centre. The outdoor walking included interval training every Tuesday and Thursday. Aerobic exercise training was given every other day in the gym and in the pool. Individual physiotherapy and relaxation were given four days a week

|

|

Time

|

Day

|

|

0745 - 0825

|

Outdoor walking/interval training

|

|

0830 - 0900

|

Stretching class

|

|

0900

|

Breakfast

|

|

0930

|

Horizontal training

|

|

1000

|

|

|

1030 - 1130

|

Pain management school

|

|

1130

|

|

|

1200 - 1245

|

Aerobic exercise training (gym or pool)

|

|

1300 - 1330

|

Individual physiotherapy

|

|

1400 - 1445

|

Dinner

|

|

1615 - 1700

|

Relaxation

|

Physical-medical rehabilitation

Specific diagnosis and treatment of muscle pain according to the protocol of Dr. Travell, forms the basis for the patients’ pain comprehension and the therapeutic approach. To reveal myofascial trigger points as a possible cause of their pain, the diagnostics is based on the patients’ medical history, pain mapping (of each patients pain distribution), comparison of their pain distributions with the Travell and Simons charts of trigger point pain patterns, plus range of motion testing and palpation (2). Trigger points are eliminated through ischemic compression or intermittent spray and stretch, to allow stretching of affected muscles without increasing the pain. A lasting effect requires elimination of perpetuating factors (that contribute to prolonging the pain), self-stretches and a gradual increase in fitness and strength after a normal range of motion has been established. Individual physiotherapy according to Dr. Travell’s protocol was given four times a week (2).

Aerobic exercise was performed through outdoors walking every morning and with inclusion of interval training twice a week, in addition to intermittent aerobic training in the gym and in the pool every other day. Maximal intensity was 60 - 70 % of the patients’ maximum heart rate. Unnecessary muscle soreness was avoided by minimizing eccentric strain, i.e. contraction of a muscle while it is being stretched. Patients were warned not to overdo their training. They were encouraged to recognize their bodies’ signals, to take breaks at need or do the exercises in their own individual tempo. Instruction in general stretching exercises was given after the morning walk.

Relaxation was partly carried out alone in bed (so called horizontal training) as a break during a busy day of treatment, as well as in the group at the end of the day, listening to a CD with music and a voice emphasizing progressive muscle relaxation, deep abdominal respiration and visualization.

Medicational adjustment was offered at need. Regular intake of addictive analgesics and muscle relaxants was discouraged. A combination of tramadolhydrochloride (50 mg) and paracetamol (500 mg) was the preferred pain reliever given only at need. An evening dose of trimipramine 10 mg, was offered to patients with sleep problems, and increased if necessary, until satisfactory sleep was achieved (usually 10 - 30 mg).

Psychosocial intervention

A psychoeducational approach was chosen with an 18-hour pain management course designed by our Centre. A rheumatologist, a practitioner in physical medicine and rehabilitation, a resident doctor, physiotherapists, nurses, a cook and a chaplain taught on the course. Part 1 dealt with pain, with an emphasis on myofascial pain, perpetuating factors and sensitizing processes in the nervous system. Fibromyalgia was presented through a biopsychosocial model of understanding. Part 2 dealt with pain management strategies with psychologically oriented themes such as positive thinking, stress management, self image, emotional self-consciousness and the importance of setting limits and taking control over one’s life. The importance of communication and family relationships, nutrition and sleep were highlighted. Part 3 consisted of group discussions where the patients chose relevant topics, watched videos and planned their lives after discharge. Everyone made their own detailed «timetable» for their first two weeks at home.

Social interplay between patients was deliberately encouraged. They experienced a break from their home circumstances, met others in the same situation and were encouraged to find new friends and strengthen their social network. There were social arrangements, hobby workshops and, if needed, the possibility of individual consultations with their doctor or chaplain. A cognitive therapeutic approach with focus on active coping strategies ran as a common thread throughout the programme.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed with the statistics programme SPSS, version 11.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). Missing values at discharge were replaced by values on arrival. Only patients who completed the 6 and 12-month questionnaires were included in the follow-up investigations. Baseline differences between those who did and did not complete the follow-up questionnaires were assessed by independent t-tests for continuous data and Mann-Whitney’s U tests for ordinal data. Change over time from point of arrival was assessed with paired t-tests for continuous data and with Wilcoxon’s rank-sum-test for ordinal or dichotomised data. Temporal changes in global subjective improvement and in quality of life, as compared to status on arrival, were assessed with Wilcoxon’s rank-sum-test using a so-called dummy variable (0 = unchanged) as baseline. Level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Average treatment time was 27.4 days (SD 3.6 days). The response rate after 6 months was 76 % (n = 151 respondents) and after one year 70 % (n = 140 respondents). The only significant baseline differences between those who did and did not complete the follow-up questionnaires, were a somewhat higher proportion of home keepers/others (7 to 1) among those who failed to complete the 6-month follow-up and somewhat longer education (12.3 years versus 11.5 years) among patients that failed to complete the 1-year follow-up.

At discharge, patients showed significant improvement in all outcome measures, and the NHP subscales were well in line with the corresponding VAS scales (tab 3). 149 patients (75 %) felt better or much better (tab 4). While three patients who did not have fibromyalgia at baseline, fulfilled the ACR-90 criteria at discharge, 50 patients fulfilling the ACR-90 diagnostic criteria on arrival no longer met the criteria at departure. These 50 patients were older (49 years vs. 46 years, p = 0.041) and had fewer tender points on arrival (14.6 vs. 15.8, p = 0.002) than those who still met the criteria at discharge. Regression analyses, controlling for age and number of tender points, showed that these 50 patients had achieved a significantly greater improvement in all outcome variables, except work capacity.

|

Table 3 Change from arrival to discharge and to 6-month and 12-month follow-up. Values are mean (SD) and also number of patients that fulfil the ACR-90 criteria. VAS: Visual analogue scale. NHP: Nottingham health profile. FIQ: Fibromyalgia impact questionnaire

|

|

Arrival

|

Discharge

|

6 months

|

12 months

|

|

Outcome variable

|

n = 200

|

n = 200

|

n = 151

|

n = 140

|

|

Pain (VAS)

|

65 (20)

|

51 (24)1

|

57 (24)1

|

59 (24)2

|

|

Pain (NHP)

|

71 (24)

|

57 (31)1

|

66 (28)2

|

63 (24)1

|

|

Fatigue (VAS)

|

63 (26)

|

47 (28)1

|

53 (27)1

|

57 (28)2

|

|

Energy (NHP)

|

54 (34)

|

26 (31)1

|

37 (35)1

|

35 (35)1

|

|

Poor sleep (VAS)

|

53 (28)

|

43 (29)1

|

43 (27)1

|

45 (28)2

|

|

Poor sleep (NHP)

|

52 (30)

|

47 (32)3

|

44 (31)2

|

41 (30)1

|

|

Depression (VAS)

|

34 (29)

|

24 (25)1

|

31 (29)

|

32 (29)

|

|

Emotions (NHP)

|

30 (26)

|

15 (21)1

|

21 (26)1

|

20 (25)1

|

|

Anxiety (FIQ-VAS)

|

51 (31)

|

35 (30)1

|

42 (32)2

|

42 (33)1

|

|

NHP total score

|

43 (16)

|

30 (17)1

|

36 (19)1

|

34 (19)1

|

|

FIQ total score

|

62 (16)

|

48 (18)1

|

54 (19)1

|

54 (21)1

|

|

Number of tender points

|

14.2 (3.6)

|

12.1 (4.3)1

|

|

|

|

Work capacity4

|

0.66 (0.2)

|

0.72 (0.2)1

|

|

|

|

ACR-90 criteria(yes/no)

|

167/33

|

120/801

|

|

|

|

[i]

|

|

Table 4 Global subjective improvement at discharge and after 6 and 12 months and change in quality of life after 6 and 12 months

|

|

Departure (n = 200)

|

|

6 months (n = 151)

|

|

12 months (n = 140)

|

|

Number

|

(%)

|

|

Number

|

(%)

|

|

Number

|

(%)

|

|

I feel

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Much worse

|

0

|

|

|

3

|

(2)

|

|

0

|

|

|

Worse

|

14

|

(7)

|

|

11

|

(7)

|

|

25

|

(18)

|

|

Unchanged

|

37

|

(19)

|

|

73

|

(48)

|

|

62

|

(44)

|

|

Better

|

118

|

(59)

|

|

52

|

(34)

|

|

37

|

(26)

|

|

Much better

|

31

|

(16)

|

|

12

|

(8)

|

|

16

|

(11)

|

|

P-value for change compared to arrival

|

< 0.001

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

My quality of life has become

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Much better

|

|

|

|

4

|

(3)

|

|

0

|

|

|

Worse

|

|

|

|

8

|

(5)

|

|

2

|

(1)

|

|

Unchanged

|

|

|

|

73

|

(48)

|

|

51

|

(36)

|

|

Better

|

|

|

|

53

|

(35)

|

|

63

|

(45)

|

|

Much better

|

|

|

|

13

|

(9)

|

|

24

|

(17)

|

|

p-value for change compared to arrival

|

< 0.001

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

p-value for change from 6 to 12-month follow-up

|

< 0.001

|

Symptoms were significantly less intense than upon arrival during the entire follow-up period (tab 3). The anxiety dimension showed lasting improvement in contrast to depression (tab 3). After 12 months 37 % still felt better or much better, and quality of life had gradually increased, as 62 % described it as better or much better (tab 4). A significantly greater number of patients had become actively employed, and fewer were reported sick. At the same time there was also an increase in the number of patients on disability pension. After 12 months 69 % were still exercising on a regular basis at least twice a week, 83 % for at least 30 min and 65 % so intensely that they most often or always became sweaty and breathless. The exercise modalities varied.

Discussion

Our results are in line with recently developed evidence-based guidelines for treatment of patients with chronic, widespread musculoskeletal pain (7, 18). Multidimensional rehabilitation gave rapid and long-lasting improvement to the patients. Our rehabilitation programme was more extensive than most other programmes, and the specific myofascial pain treatment makes it special. The effect of myofascial pain treatment has not yet been tested on fibromyalgia, but Borg-Stein emphasizes the importance of discovering and treating peripheral pain generators in order to diminish the total pain burden, ease the rehabilitation process and to reduce the peripheral drive for central sensitization (26). The myofascial pain component is commonly overlooked, a fact that often leads to unnecessary medical examinations and prolonged suffering (27). Moreover, myofascial pain treatment has been recommended as a natural part of a multidimensional rehabilitation programme for patients with fibromyalgia (28, 29).

Our study was not designed to conclude on the effects of each individual element or on myofascial pain treatment as such. We found, however, that Dr. Travell’s approach was extremely useful in achieving a mutual understanding between patient and therapist (2). The patients perceived that the findings from our clinical examination, the explanations given and the Travell trigger point pain patterns were well in line with their own experience. They experienced increased credibility, felt respected and cared for and were reassured that this was harmless muscle pain, which they would be able to influence themselves. This created confidence and removed resistance when the impact of psychosocial factors on their symptom level was addressed.

The challenge is to achieve even further symptom reduction in patients over time, and our rehabilitation programme undoubtedly has a potential for improvement. Greater emphasis could be placed on the elimination of perpetuating factors that prolong the condition, and on optimizing exercise intensity. The psychosocial intervention could be further developed in accordance with more recent developments in cognitive behavioural therapy and include more specialized psychological competence.

To be ready to make important changes in life is a process of maturation. The 50 fibromyalgia patients who responded so well to treatment that they no longer fulfilled the diagnostic criteria, had possibly come further in this process of readiness to change than the others. Multidimensional rehabilitation of pain clinic- and fibromyalgia patients has been shown to increase their motivation for change, and this has in turn been associated with improvement (30).

In practice, it was impossible to make this study randomized, blinded and controlled, but most of our therapeutic elements have been documented in other controlled studies (7, 18, 21). We included patients that traditionally would have been excluded from a treatment study, and this may have weakened our results. We chose, however, to present a population that was representative for all of our pain patients. They were seriously affected with long-lasting symptom duration, and only a minority were actively employed. They were without doubt, in need of specialized rehabilitation. The tender point assessments were performed by the patients’ doctor, who could not be blinded to the time factor. This may have biased our finding that 50 patients (30 % of the 167 included) no longer fulfilled the fibromyalgia diagnosis at discharge. The fact that these patients also showed significantly greater improvement in all but one of the remaining variables, does however strengthen our finding.

Conclusion

A 4-week multidimensional rehabilitation programme based on a biopsychosocial paradigm for understanding chronic muscle pain and fibromyalgia, had an extensive, rapid and lasting effect. Our results support those in other randomized, controlled studies. To prevent the development of widespread or recurring pain, one should offer the patient adequate intervention as early as possible. It is a challenge to promote the use of, and further develop, the existing evidence-based guidelines.