Individuals who have experienced catastrophes, accidents or unexpected deaths have an increased incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (1 – 4). According to randomised controlled studies, cognitive-behaviour therapy seems to be the most effective measure to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder in persons who have experienced an event such as an accident, fire, violence or unexpected death (5). Municipal crisis teams have been established to provide psychosocial follow-up after sudden deaths that affect both individuals and larger groups, for example in connection with catastrophes, accidents or suicide (6). People who experience acute events and crises also use their own network, their regular general practitioner (GP) and municipal out-of-hours services.

Bergen Municipality established The Personal Crisis Support Team at Bergen Accident and Emergency Department in November 2005, as a supplement to the municipality’s crisis team. The Team is on duty 7 days a week and is staffed with psychiatric nurses and social educators who have been educated in mental health care. Support is offered to persons who have problems to tackle everyday life because they have experienced an unexpected event, a life crisis or a psychosocial crisis. Anyone who worries about someone who does not seek help for themself or serious mental disorder in next-of-kin may also take contact. The personnel are meant to give acute help in a crisis and to offer two to three follow-up conversations. When more long-term help is needed the Team will help to establish contact with other health services.

The purpose with this study was to map contacts to the Team in 2006, which problems the patients had and to whom they were further referred.

Material and methods

All contacts to the Personal Crisis Support Team in Bergen in 2006 were included in the study. Data were retrieved from medical records and notes that Team personnel had written from each contact and conversation (to ensure reporting between duties). The following information was retrieved from medical records for each conversation: home municipality, sex, age, type of contact (telephone or physical meeting), time of contact (time of day, month), institution that made the referral, cause for contact, data about the conversation (conversation number, number of people present, length of the conversation) and to where the patient was further referred. The causes of contact were divided into 48 single categories and thereafter grouped into 10 main categories in four areas: life crisis (A), possible symptom of mental disorder (B), composite problem (C) and unknown cause (D) (Box 1).

Box 1

Main categories of reasons for contact

A. Life crisis

Serious life events, defined as unexpected single events such as loss of partner, sudden death, serious accident or violence (physical, sexual, mental) that the person experiences as very stressing, traumatic or even insulting (11 single categories).

Worries about others, defined as contacts from others than the main person concerning uncertainty about whether someone in the family or network has serious mental disorder or a substance abuse problem (8 single categories).

Interaction problem in the family, defined as problem between generations (parents and children/adolescents) or between married couples/partners (5 single categories).

Other crises, including economic problems, somatic disease or housing problem (5 single categories).

B. Symptom of mental disorder

The categories are used when the patient has previously had a mental disorder or describes a symptom picture, which according to the personnel’s assessment raises suspicion of a mental disorder.

Depression and suicidal tendency (1 single category)

Substance abuse (1 single category)

Anxiety (1 single category)

Other (6 single categories)

C. Composite problem

These categories are used when there have been life crisis problems in addition to symptoms of mental disorder.

D. Unknown cause

The data are recorded without establishing a personnel register. Each person was given a code in the first phase of the recording. After recording in the data file, the codes for persons and home municipalities were recoded, so it would not be possible to track data back to individual patients. The statistics programme SPSS version 15.0 was used to provide descriptive analyses.

Results

Description of patients

901 patients contacted the Crisis Support Team in 2006. Of these 23 patients contacted the Team for the first time in 2005. 782 patients (87 %) stated that Bergen was their home municipality and this included persons for whom other home places were registered. 91 patients (10 %) came from other municipalities in Hordaland, while 23 patients (3 %) came from other counties. For five patients a home municipality was not registered.

Two thirds of patients were women and one third were men. About every third patient was in the age 19 to 30 years (tab 1). In the age group below 18 years 80 % were women, while in the other age groups two thirds were women.

|

Table 1 Sex and age of patients who contacted the Personal Crisis Support Team in 2006 (N = 901)

|

|

Women

|

|

Men

|

|

All

|

|

|

Age group (years)

|

Number

|

(%)

|

|

Number

|

(%)

|

|

Number

|

(%)

|

|

|

1 – 18

|

44

|

(7.3)

|

|

11

|

(3.7)

|

|

55

|

(6.1)

|

|

|

19 – 30

|

186

|

(30.9)

|

|

94

|

(31.4)

|

|

280

|

(31.1)

|

|

|

31 – 40

|

133

|

(22.1)

|

|

81

|

(27.1)

|

|

214

|

(23.8)

|

|

|

41 – 50

|

126

|

(20.9)

|

|

57

|

(19.1)

|

|

183

|

(20.3)

|

|

|

51 +

|

113

|

(18.8)

|

|

56

|

(18.7)

|

|

169

|

(18.8)

|

|

|

Total

|

602

|

(100)

|

|

299

|

(100)

|

|

901

|

(100)

|

|

Way of making contact and causes

About as many patients contacted the Crisis Support Team by telephone (n = 446) as by personal meeting (n = 455). 464 patients in all (52 %) contacted the Team on their own initiative, while a doctor or nurse from Bergen Accident and Emergency Department referred 208 patients (23 %). The other 226 patients (25 %) were referred from next-of-kin or the help apparatus, while referral information was missing for three patients.

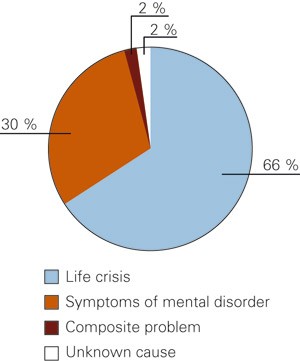

Most patients (66 %) who took contact had no mental disorder themselves, but described various life crises (fig 1). A little less than a third of patients (30 %) had symptoms of mental disorder. Within the category life crises; serious life events were the most important group and worries about others the second most frequent (tab 2). Within the category mental disorders the largest group was depression and suicide problems. Life crises were recorded for 69 % of women and 59 % of men. 27 % of women and 36 % of men presented with possible symptoms of mental disorders. Of the 48 response groups (across categories) most concerned worries about own children. The second most frequent response group was depression and suicide problems, while break-up of partnerships came third (tab 3). In the age group 1 – 18 years sexual assaults was the most frequently used response group, with 25 % of patients. Six of the single response groups were not used.

Figure 1 Distribution of causes for contact to the Personal Crisis Support Team (n = 901)

|

Table 2 Causes for referral to the Personal Crisis Support Team in 2006 (N = 901)

|

|

Cause of contact

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Main category

|

Subcategory

|

Number

|

|

( %)

|

|

A. Life crises

|

|

590

|

|

|

(65.5)

|

|

|

Serious life events

|

|

265

|

|

|

(29.4)

|

|

Worries about others

|

|

207

|

|

|

(23.0)

|

|

Interaction problem in the family

|

|

67

|

|

|

(7.4)

|

|

Other crises

|

|

51

|

|

|

(5.7)

|

|

B. Symptom of mental disorder

|

267

|

|

|

(29.6)

|

|

|

Depression and suicidal tendency

|

|

83

|

|

|

(9.2)

|

|

Substance abuse

|

|

44

|

|

|

(4.9)

|

|

Anxiety

|

|

44

|

|

|

(4.9)

|

|

Other

|

|

96

|

|

|

(10.6)

|

|

C. Composite problems

|

21

|

|

|

(2.3)

|

|

|

Loss of partner and depression

|

|

11

|

|

|

(1.2)

|

|

Other composite problems

|

|

10

|

|

|

(1.1)

|

|

D. Unknown cause

|

23

|

|

|

(2.6)

|

|

|

Total

|

|

901

|

|

|

(100)

|

|

|

Table 3 The 10 most common causes for referral to the Personal Crisis and Support Team in 2006 (N = 901). Categories (A-D) as in Table 2

|

|

Category

|

Number

|

(%)

|

|

Worries about children (A)

|

97

|

(10.8)

|

|

Depression/suicidal tendency (B)

|

83

|

(9.2)

|

|

Loss of partner (A)

|

63

|

(7.0)

|

|

Other mental disorder (B)

|

60

|

(6.7)

|

|

Substance abuse (B)

|

44

|

(4.9)

|

|

Anxiety (B)

|

44

|

(4.9)

|

|

Interaction problem (partner) (A)

|

36

|

(4.0)

|

|

Worries about others (A)

|

36

|

(4.0)

|

|

Sudden death because of physical disease/accident in close (A)

|

33

|

(3.7)

|

|

Other sudden life occurrences (A)

|

33

|

(3.7)

|

|

Other causes

|

372

|

(41.3)

|

|

Total

|

901

|

(100)

|

Conversations and referrals

2090 conversations were recorded with the Crisis Support Team in 2006. The mean number of conversations per month was 174 (variation 100 – 223). Almost half of the conversations (n = 935; 45 %) took place during daytime from Monday to Friday, the rest were evenly distributed between evenings Monday to Thursday (29 %) and evening Friday and in weekends and holidays (26 %). Mean length of the conversations was 43 min, while the median time was 30 min. 45 % of the conversations lasted for 20 min or shorter and 39 % of the conversations lasted for more than 45 min. Among conversations that occurred during physical meetings with Team personnel (n = 965), the patient was alone with one person from the Team in 739 conversations (77 %) while two persons (other than Team personnel) were present during 172 conversations (18 %) and three or more persons were present during 54 conversations (6 %).

780 (37 %) of all conversations with Team were follow-up of previous contacts. 1741 concerned referrals to others (tab 4). More than half of referrals were to regular GPs or out-of-hours services (54 %). Included in this number were also patients with a need for referral to a specialist health service within the mental health care providers. Of 414 referrals to a GP on duty within the out-of-hours service, 91 contained questions on further referral to psychiatric specialist health care, 117 concerned assessments of suicide and the rest were about other conditions. Less than every 10th referral was to a municipal mental health service or municipal crisis team. Referrals were also made to providers that did not require referral from a doctor; i.e. municipalities, counties, national or private institutions.

|

Tabell 4 Referrals from the Personal Crisis Support Team to other health care providers i 2006 (N = 1 741)

|

|

The referring health care provider

|

Number

|

(%)

|

|

Regular general practitioner

|

519

|

(29.8)

|

|

Doctor on duty in the out-of-hours services

|

414

|

(23.8)

|

|

Municipal psychiatric specialist service /crisis team

|

140

|

(8.0)

|

|

Private psychologist/students’ mental health service

|

71

|

(4.1)

|

|

Social services

|

59

|

(3.4)

|

|

Child protection service

|

39

|

(2.2)

|

|

Psychiatric acute team (specialist health service)

|

37

|

(2.1)

|

|

Police

|

35

|

(2.0)

|

|

Family therapy/course on cohabitation/marriage

|

33

|

(1.9)

|

|

User organizations

|

33

|

(1.9)

|

|

Other public and private health care providers

|

361

|

(20.8)

|

|

Total

|

1 741

|

(100)

|

By analysing the group of patients who had their first conversation with the Crisis Support Team in the first quarter of 2006, we got an impression of the number of conversations for each patient. This cohort consisted of 221 patients who had 601 conversations during 2006. The number of conversations per patient varied from 1 to 36. Half of the patients only had one conversation during the entire period. 80 % of patients had three or fewer conversations.

Discussion

Patients who contacted the Personal Crisis Support Team in 2006 presented with a great variety of problems, but a majority came because of some kind of life crisis – for example worries about children or break-up of partnerships. A smaller proportion came because of mental disorders. A majority of patients were referred further, most of them to their regular GP or to a GP on duty within the out-of hours services. Many of the referrals to a GP can be explained by the fact that the Team cannot refer directly to Specialist Services.

The number of conversations may be underreported as the Team was in its initial phase when data were retrieved; some conversations had not been summarised at the time and recording routines changed as the organisation developed. The groups of contact causes within the categories are not strictly defined; some causes could be placed in more than one group – e.g. worries about others and communication problems may be expressions of someone in the family having a mental or substance abuse problem, but it may also represent the type of difficulties that naturally emerge in different phases of life.

The age group that contacted the Team most frequently was 19 – 30 years. There are several reasons for why there is a greater need for the type of help offered by the Team to people of this age than of other ages. They are in a phase of life that requires adaptation to many roles (education, work, cohabitation/marriage) and although stable and supporting contacts are especially needed, they are not necessarily in place. Bergen has a large group of students and others who do not live permanently in the town; they may not have easy access to or know about other health services in Bergen. The proportion of women dominated in all age groups, which is line with women using health services more than men in general (7).

Ways of contact and reasons for contact

The fact that telephone contact and physical presence was equally common, may express that flexibility with respect to type of contact is important for accessibility. About half of the patients took contact on their own initiative. Referral of every 4th patient by Bergen Accident and Emergency Department may indicate that the Crisis Support Team cover a need for conversation that is not offered by the out-of-hours services. Some patients who came to a GP within the out-of-hours service would probably have been without an offer if the Crisis Support Team had not existed, while others would have been referred to their regular GP or their own network.

A majority of patients came to discuss life crises that Team members did not classify as mental disorders. The life crisis term used here includes both acute events and more long-lasting stress situations within close relationships. If the patient does not get enough support, unexpected occurrences and communication problems within families may, however, be risk factors for developing mental disorders. Patient descriptions of ailments will overlap between categories because crisis reactions and symptoms of anxiety and depression may have a common content. Occurrence of acute events, duration of symptoms, depth and extent of problems will normally separate normal crisis reactions from mental disorders (2,3). In this study, worries about others and communication problems in the family were classified as a life crises. Such problems may be an expression for one in a family having a serious symptom of a mental disorder or a substance abuse problem without getting sufficient treatment. Symptoms of mental disorders may start in new stressing life situations as for example a relational problem, moving, change of job or start of studies (3). The Crisis Support Team’s personnel are meant to have competence in basic diagnostic categories.

Through guidance and conversations aimed at defining problems, the Personal Crisis Support Team may provide important support to parents who worry about children. The Team is more accessible and spends more time on conversations than a GP can offer and it may be easier to bring children, and others one worries about, to a Crisis Support Team than to a doctor. In addition psychosocial crises is an area where several professional groups have valuable competence. Depression and suicide problems are conditions that require assessments by a doctor. In these cases a conversation with the Team is not sufficient, but the personnel may contribute to bringing patients with undiagnosed or untreated mental disorder to a doctor for assessment of treatment needs.

Break-up of partnerships was the most frequent serious life crisis among those who took contact. Municipal crisis teams were not used for break-up of personal relationships. However, it is our experience that more people contact their regular GP, out-of-hours doctor and own network in crises concerning partners. The Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services have summarised effective measures in psychosocial crises (5); in this summary they have left out life crises such as break-up of partnerships and limited the study to single events such as suicide, fire, accident and violence. Nevertheless, experience and research shows that break-up of partnerships may affect people very hard (8). In some descriptions of a mental crisis, break-up of partnerships and infidelity are unexpectedly included, and this is related to the feeling of loss (9).

Conversations and referrals

A mean of two conversations per patient shows that the services offered by the Team were carried out in accordance with the aim, with a few conversations per patient. This may indicate that patients managed on their own, or were further referred to other instances. One explanation may be that patients did not get what they expected from the Team and therefore did not see the use of coming back. The Crisis Support Team is meant to map and sort the patients’ problems and give guidance and help so patients themselves may contact the appropriate provider of help. For many of these patients a conversation may be sufficient. Follow-up conversations from the Team comprised 37.5 % of the conversations, but the patients could also be referred to one or more health providers. Literature on the topic emphasises that psychosocial follow-up requires cross-disciplinary cooperation (1). More than half of all referrals from the Team were to a doctor, which may mean that cooperation with a doctor is essential. For example, a physician must be the first to assess patients who need follow-up from a psychologist or a psychiatrist. Other service providers are many-sided and include both public and private providers.

Every third conversation lasted for more than 45 min, which indicates that consultations with the Team are relatively time-consuming. Descriptions of good crisis help emphasises the importance of letting the person tell about what has happened (1 – 4, 6). This requires longer conversations than what can normally be offered within the out-of-hours services.

No low- threshold offers have been available, neither for those who worry about their own children nor for those who experience break-up of partnerships. Those who need such help must wait for a long time and accessibility is therefore low.

The Personal Crisis Support Team is readily accessible and can give individually tailored help and assistance for a shorter period of time. Early intervention in crises and prevention of health problems is based on the assumption that treatment is available when crises occur (3, 4, 6, 10, 11). Conversations offered should contain emotional and practical support, counselling on normal crisis reactions, cognitive mastering techniques and self help methods, as well as mapping of vulnerability factors (4, 10, 11). The aim is to contribute to support each individual’s coping. The Crisis Support Team’s interventions have something in common with the treatment offered by specialist services. One may say that the Team offers acutely needed contact in a way that places it right in the midst of offers from out-of-hours services, regular GPs and psychologists.

Conclusion

This study shows that the low-threshold help offered by the Personal Crisis Support Team was used by patients in all age groups and most often by women. Patients presented with symptoms of mental disorders and took contact about various life crises. The Team referred people to other care providers, most often to physicians within the regular GP on duty within the out-of-hours services.

The number of users and causes for contact show that the low-threshold service is used in connection with psychosocial crises in a wide sense. In Bergen one has chosen to organize this service in conjunction with the out-of-hours services. In smaller municipalities, it would not be practical to organize a service requiring regular employees and long working hours in the same way. A low- threshold service such as the Personal Crisis Support Team should be evaluated. A user- survey would provide answers to how useful the services have been to patients and whether the patients felt they had been referred to the right care provider.