Bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) are prevalent diseases that affect the health of individuals to a large extent and are associated with high costs for society. International guidelines for treatment of asthma (Global Initiative for Asthma [GINA]) (1) and COPD (Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD]) (2) have been developed, but studies from Sweden (3) and the UK (4) have shown that diagnostic precision is often low.

For COPD, objective measurement of lung function with spirometry is required to diagnose the condition, classify the degree of severity and to follow up lung function (5). Spirometry seems to be used less frequently than recommended, in Norway as in other western countries (6, 7), but apart from a questionnaire (1996) there are few reports on use of spirometry in Norway (8). Patients with a COPD diagnosis have often been treated with medication documented to be effective and approved for the asthma indication (8). New regulations on reimbursement from 1.07.2006 require spirometry assessments in asthma and COPD, and the list of drugs that are approved for reimbursement for COPD has been restricted (9).

Unclear use of diagnoses and insufficient documentation of practice for diagnosing obstructive lung disease in Norway, triggered us to map the use of the diagnoses COPD, asthma and «heavy breathing» in a sample of regular GP practices in Trøndelag. We also wished to assess the use of spirometry, prescriptions, contacts to the out-of-hours services, outpatient consultations and hospitalisations for the patient groups. The study covers the period 1995 – 2004, i.e. before implementation of new prescription regulations.

Material and methods

The study included all patients 7 years of age and older, registered with the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) diagnoses: COPD (R95), asthma (R96) or «heavy breathing» (R02) in electronic medical records in the period 1.1.1995 – 31.12.2004 at one of the five GP practices in Steinkjer or three selected practices in Trondheim.

By use of an extraction programme (Mediata AS), data on use of diagnoses, prescriptions and spirometry were retrieved from RGP records. For data technical reasons, spirometry data were missing for one practice for the entire period and for another one for the years 1999 – 2002. Prescription information was based on drug names put down in the medical records and ATC codes from reimbursement paragraph 9.2 (bronchial asthma and COPD).

For patients with the diagnoses R95, R96 or R02, identified in GP practices, information on contacts to the out-of-hours services (due to these diagnoses) was retrieved from out-of-hours services in Steinkjer (1995 – 2004) and Trondheim (1995 – 2002). For patients with the diagnoses asthma (ICD-10-codes: J45.0 – 9 and J46), COPD (J43.0 – 9 and J44.0 – 9) and chronic bronchitis (J41.0 – 8 and J42) identified in Levanger hospital (1999 – 2004) or St. Olavs hospital (2001 – 04), information was collected during outpatient consultations and at admission.

Analyses

The analyses are based on the total number of patients registered with COPD, asthma or «heavy breathing». We used three diagnosis groups; COPD, asthma (without COPD) and «heavy breathing» (without COPD and/or asthma). No patient was included in the analysis more than once per calendar year.

For Steinkjer, the annual proportion of inhabitants who had contacted a GP because of one of the diagnoses mentioned could be calculated, as the data included all GP practices. Population data for the municipality of Steinkjer were retrieved from Statistics Norway.

The statistics programme SPSS for Windows (version 14.0) was used for all analyses. The Norwegian Directorate of Health and The Data Inspectorate approved the study and the Independent Ethics Committee in Central Norway Regional Health Authority recommended it.

Results

The analysis material includes 10 802 contacts (COPD 2 533, asthma 7 061, «heavy breathing» 1 208) in GP practice for 4 486 patients from either Steinkjer or Trondheim.

Use of diagnoses in Steinkjer

The proportion of inhabitants in Steinkjer municipality who contacted a GP because of COPD increased through the observation period for both sexes and in all age groups (tab 1). The proportion of inhabitants with the diagnosis asthma was quite stable for both sexes in the age group 7 – 19 years and somewhat on the increase for the age groups between 20 and 54 years. For the oldest age groups there was a tendency for a weak reduction in the use of the asthma diagnosis. The diagnosis «heavy breathing» was not so much used during the observation period.

|

Table 1 Proportion of inhabitants (%) registered in general practice with at least one annual contact due to the diagnoses chronic obstructive lung disesae (COPD), asthma or «heavy breathing» in Steinkjer municipality 1995 – 2004

|

|

Time-period

|

|

Sex, diagnosis, age (years)

|

1995 – 96

|

1997 – 98

|

1999 – 2000

|

2001 – 02

|

2003 – 04

|

|

Women

|

N = 18 680

|

N = 18 672

|

N = 18 688

|

N = 18 872

|

N = 18 907

|

|

COPD

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

35 – 44

|

0.0

|

0,1

|

0.1

|

0.3

|

0.4

|

|

45 – 54

|

0.3

|

0.7

|

0.7

|

0.8

|

0.9

|

|

55 – 64

|

0.8

|

1.2

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

2.4

|

|

65+

|

0.9

|

1.5

|

2.2

|

2.7

|

3.4

|

|

Asthma

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 – 19

|

3.7

|

2.9

|

3.5

|

3.4

|

3.1

|

|

20 – 34

|

1.7

|

2.0

|

2.0

|

2.5

|

2.8

|

|

35 – 44

|

1.7

|

2.1

|

2.1

|

2.3

|

2.3

|

|

45 – 54

|

1.9

|

2.1

|

2.7

|

2.8

|

2.1

|

|

55 – 64

|

4.2

|

3.1

|

3.5

|

3.6

|

2.1

|

|

65+

|

2.5

|

2.6

|

2.9

|

3.0

|

2.5

|

|

Heavy breathing

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 – 34

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.2

|

0.2

|

|

35 – 44

|

0.1

|

0.3

|

0.1

|

0.2

|

0.4

|

|

45 – 54

|

0.3

|

0.1

|

0.4

|

0.4

|

0.3

|

|

55 – 64

|

0.3

|

0.2

|

0.2

|

0.4

|

0.5

|

|

65+

|

0.3

|

0.5

|

0.6

|

0.8

|

1.0

|

|

Men

|

N = 18 692

|

N = 18 488

|

N = 18 478

|

N = 18 530

|

N = 18 540

|

|

COPD

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

35 – 44

|

0.0

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.3

|

|

45 – 54

|

0.2

|

0.5

|

0.4

|

0.7

|

0.6

|

|

55 – 64

|

0.9

|

1.1

|

1.2

|

1.6

|

2.1

|

|

65+

|

1.5

|

2.4

|

3.1

|

3.8

|

5.0

|

|

Asthma

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 – 19

|

4.1

|

3.9

|

3.7

|

4.4

|

4.4

|

|

20 – 34

|

0.9

|

1.2

|

1.5

|

2.3

|

2.3

|

|

35 – 44

|

1.3

|

1.7

|

1.8

|

2.1

|

2.1

|

|

45 – 54

|

1.6

|

2.2

|

2.1

|

2.4

|

2.6

|

|

55 – 64

|

2.5

|

3.1

|

3.1

|

3.3

|

2.1

|

|

65+

|

3.2

|

2.7

|

2.9

|

2.5

|

1.9

|

|

Heavy breathing

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 – 34

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.2

|

0.2

|

|

35 – 44

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.0

|

0.3

|

0.3

|

|

45 – 54

|

0.1

|

0.3

|

0.2

|

0.4

|

0.5

|

|

55 – 64

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.5

|

0.3

|

|

65+

|

0.2

|

0.5

|

0.8

|

1.1

|

1.2

|

Spirometry

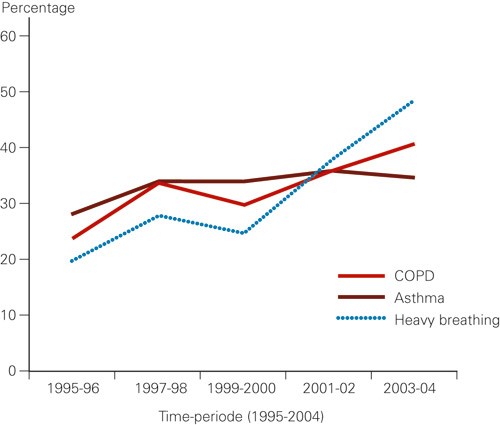

The proportion of COPD patients with spirometry measurements increased from 24 % in 1995 – 96 to 41 % in 2003 – 04 (fig 1). For asthma patients, the use of spirometry was about 30 % through the entire observation period.

Figure 1 The percentage of patients with the diagnosis chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), asthma, or «heavy breathing» in GP practice who had had at least one annual spirometry measurement

Drugs that are reimbursed completely «blue prescription»

During the entire observational period about four of five patients with COPD or asthma were treated with a drug under the complete reimbursement scheme; patients with the symptom diagnosis «heavy breathing» received substantially fewer drugs in this scheme (tab 2).

|

Table 2 Proportion of patients with the diagnoses Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), asthma and «heavy breathing» registered with prescription of drugs on blue prescription, inhalation steroids (ATC-code R03BA) and combination drugs (ATC-kode R03AK) in general practice in Steinkjer and Trondheim 1995 – 2004

|

|

Time-period

|

|

Diagnosis

|

1995 – 96

|

1997 – 98

|

1999 – 2000

|

2001 – 02

|

2003 – 04

|

P-value¹

|

|

COPD

|

N = 288

|

N = 401

|

N = 453

|

N = 598

|

N = 793

|

|

|

Blue prescription (%)

|

81

|

88

|

88

|

80

|

76

|

< 0.001

|

|

Inhalation steroids (%)

|

62

|

65

|

57

|

29

|

13

|

< 0.001

|

|

Combination drugs (%)

|

–

|

–

|

16

|

40

|

50

|

< 0.001

|

|

Asthma

|

N = 1 208

|

N = 1 279

|

N = 1 346

|

N = 1 666

|

N = 1 562

|

|

|

Blue prescription (%)

|

85

|

83

|

82

|

81

|

77

|

< 0.001

|

|

Inhalation steroids (%)

|

64

|

63

|

59

|

37

|

24

|

< 0.001

|

|

Combination drugs (%)

|

–

|

–

|

12

|

36

|

45

|

< 0.001

|

|

Heavy breathing

|

N = 122

|

N = 148

|

N = 158

|

N = 341

|

N = 439

|

|

|

Blue prescription (%)

|

25

|

29

|

28

|

28

|

27

|

0.809

|

|

Inhalation steroids (%)

|

22

|

21

|

27

|

11

|

7

|

< 0.001

|

|

Combination drugs (%)

|

–

|

–

|

8

|

17

|

21

|

< 0.001

|

|

[i]

|

For all diagnosis groups, prescriptions of pure inhalation steroids decreased strongly in the period 1999 – 2000, and at the same time there was an increase in prescriptions of combination drugs (tab 2).

Contact with out-of-hours services

16 % (349/201) of patients with a COPD diagnosis from GP practice had been in contact with out-of-hours services the same calendar year. The proportion was quite stable over the observation period 1995 – 2004 (data not shown). In 50 % (n = 174) of the 349 cases there was a concordance in use of diagnoses, while the diagnoses asthma and «heavy breathing» were used by out-of-hours services for 44 % (n = 153) and 6 % (n = 22) of patients registered with a COPD diagnosis in GP practice.

Correspondingly, the percentage (10 % [634/6 470]) of patients with an asthma diagnosis who were in contact with the out-of-hours services remained quite stable over the observation period (data not shown). The majority of patients diagnosed with asthma in general practice were given the same diagnosis by the out-of-hours services (89 %, 567/634), while 7 % (46/634) were diagnosed with COPD and 3 % (21/634) with «heavy breathing».

Just a small proportion of patients with the diagnosis «heavy breathing» were in contact with the out-of-hours services; 2 – 4 % during the entire observational period.

Contact with hospital

19 % (324/1 666) of patients with the diagnosis COPD in GP practice came to an outpatient consultation the same calendar year. The proportion was quite stable over the years 1999 – 2004 (data not shown). The majority of these were given the same diagnosis at the outpatient clinic (90 %, 292/324), while the rest were diagnosed with asthma.

Among patients diagnosed with asthma and «heavy breathing» in GP practice, there was a substantially lower proportion that came to outpatient consultations (8 % [337/4 201] and 3 % [26/871] respectively). Among patients with an asthma diagnosis in GP practice, 72 % (242/337) were diagnosed with asthma on an outpatient basis, 27 % (92/337) were diagnosed with COPD while three patients were diagnosed with chronic bronchitis.

For one fourth (394/1 666) of patients registered to have COPD in general practice 1999 – 2004 hospitalisation was recorded the same calendar year; the majority of these (94 %, 371/394) were discharged with the same diagnosis and a minority with an asthma diagnosis (6 %, 23/394). Among patients diagnosed with asthma or «heavy breathing» in general practice, the proportion of admissions were substantially lower (4 % [159/4 201 and 3 % [30/871] respectively). More than half of these asthma patients were discharged from hospital with the diagnosis COPD (55 %, 88/159), while for 30 of patients hospitalised for «heavy breathing» 22 (73 %) were discharged with the diagnosis COPD and eight (27 %) with an asthma diagnosis.

Discussion

This study is based on data from medical records and shows how such data can be used to better understand treatment and health service expenditure for different patient groups. We have followed a large number of patients between the first and second line service and have avoided sources of error incurred by doctors under surveillance who could have improved their procedures, including use of diagnoses. Municipalities and regions may use the diagnosis systems differently, which may weaken generalisability of the results.

Diagnoses and use of spirometry

We assume that the increasing use of the COPD diagnosis can be explained by an increased awareness of this disease, but also that spirometry (a prerequisite to assign the correct diagnosis) is increasingly used. The decline in asthma diagnoses among the oldest patients supports this interpretation. An increasing prevalence of asthma after the age of 50 years may be attributed to COPD patients having been erroneously diagnosed with asthma (10). However, we do not dismiss that the prevalence of COPD may have increased.

The fact that guidelines for both asthma and COPD (1, 2) require that lung function tests are used to diagnose and follow up such patients, we had expected an even stronger increase in the use of spirometry. Our results point at an underuse of spirometry which accords with international studies (6, 711). These findings illustrate how difficult it may be to implement use of such guidelines in clinical work (12). Our findings show differences in diagnoses between GP practice, out-of-hours services and hospitals, which indicates that diagnostic precision can be improved.

Prescriptions

We observed that the prescription pattern quickly changed from inhalation steroids to combination drugs for both COPD and asthma patients. Prescription of inhalation steroids and combination drugs give grounds for reimbursement in asthma, but not for COPD. The pure steroids do not have an improved indication for serious COPD (FEV1< 50 %) with frequent exacerbations. The prescription pattern that comes up in our study indicates that the splitting of previous reimbursement paragraph 9.2 to paragraphs 9.44 and 9.45 (implemented in July 2006) was effective in reducing the overuse of combination drugs for patients with mild to moderate COPD.

Use of health services

In this study we found that one of six patients diagnosed with COPD in GP practice had been in contact with out-of-hours-services during the same calendar year. The extensive use of the out-of-hours services may be explained by the fact that patients feel a need to contact health services also in afternoons/evenings and during weekends because they fear a night with breathing difficulties and the limited access to regular GPs in daytime (13). Part of the visits to out-of-hours services may be caused by patients delaying to contact their GP for as long as possible. Extensive use of out-of-hours services may indicate that information to patients on how to tackle exacerbations is not good enough. Many patients with asthma or COPD do not have individual action plans, drugs or other aids for self-treatment of exacerbations (2, 14). The RGP scheme was implemented in Trondheim as early as 1993 and in Steinkjer municipality in 2001. Implementation of the RGP scheme did not seem to affect the use of out-of-hours services for patients in Steinkjer, which accords with other assessments of the RGP scheme and use of out-of-hours services (13, 15).

We found that about one of four patients with COPD had been hospitalised during one year, while about one of five had outpatient consultations. It is reasonable that patients with serious disease have regular controls in the second-line service to identify development of chronic hypoxia, but patients with mild to moderate disease should be referred back to their regular GP. Our data (0.26 % of the population in Steinkjer had been in contact with general practice because of COPD and had been hospitalised for obstructive lung disease within one calendar year [calculations not shown]) are well in accordance with statistics from the Ministry for Health and Care Services (360 patients are hospitalised with the COPD diagnosis per 100 000 inhabitants annually [8]).

Conclusion

Changes in use of diagnoses and increased use of spirometry in obstructive lung disease indicate that the COPD diagnosis is used more correctly. Use of spirometry for diagnosing and classifying this disease in the primary health services is a prerequisite for correct treatment and use of the reimbursement system.