Values form an implicit basis of the personal encounter between patient and doctor. The equal value of all humans, irrespective of their characteristics and achievements, cannot be taken for granted. Neither can it be proven logically.

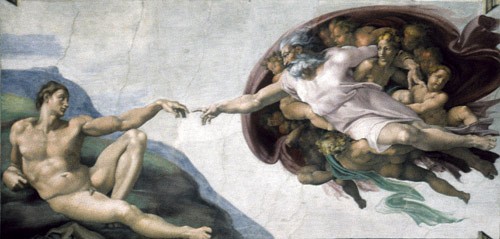

The creation of Adam. From the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. Painted by Michelangelo in the period 1508 – 12. Photo © Mikkel Østergaard/Samfoto/Scanpix.

In the UN Declaration of Human Rights, fundamental values are regarded as intuitive and self-evident. Others see values as learned and communicated through culture and religion (1). In the West, the Christian teachings on creation have had a decisive influence on how human life is viewed. The original justification for this view is found in Genesis (2).Succinctly and majestically, the narrative of the creation of all things is chronicled. At the same time, an impression of order, immutability and divine intention is communicated. The genesis is concluded by the creation of man, and completed by the Creator beholding his work and seeing that it was good. For millennia, this compact narrative has been the basis for Christian anthropology, the study of man.

First, it is stated that Man and the rest of creation have not come into being by accident, but as a result of a deliberate act by a divine creator. Man is part of creation, like everything else alive, created from the same matter and part of the larger ecosystem. To this biological body, a soul and a spiritual dimension have been added. The relational or social aspects are the fourth dimension of biblical anthropology.

The value of Man

Man is given a special role within creation, and is awarded an elevated position. Man shall rule over the rest of creation, and even more importantly, it is stated that Man is created in God’s image. This clearly means that Man has divine features and that God has human features. Man has a divine signature and a special position that makes all human life sacrosanct and inviolable. Thereby, all humans have equal value.

The notion that all humans have equal value was a novel idea in the first Christian era. The Hellenic and Roman empires were both divided into classes, and the weak and imperfect were regarded with contempt. To his contemporaries, Paul’s statement in Galatians that «there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female» (2) was a radical expression of equality in value. During the introduction of Christianity to Norway a thousand years later, the idea of the value of the individual represented a divergence from old attitudes and norms.

Freedom and fall

God put creation at the disposal of Man, and gave Man the independence and freedom to make individual choices, rather than being an obedient puppet. From freedom follows responsibility. Man is the only creature held responsible for his actions.

According to the Biblical narrative, Man let himself be seduced by God’s adversary. This event, the fall of man, is depicted as a heritage which has later attached itself to all humans (2). Therefore, people cannot be classified as either good or evil. We can be cultivated to become convivial and social-minded people, but we will always retain a tinge of evil in our souls and minds, irrespective of whether we call ourselves believers or not. This concurs with all human experience – as Henrik Ibsen wrote: «To live is to battle the demons / in the heart as well as the brain.»

Pauline anthropology

Paul, who was a well educated Jew and who had grown up with Greek culture and language, writes insightfully and self-critically about human nature. He uses two Greek terms when referring to the body: soma and sarx. The spiritual nature of humans is described as either pneuma or psyche, and intelligence or reason is called nous.

The term nous can be rediscovered in the word ’paranoid’, meaning outside reason. Sarx can be translated as flesh, but has a wider meaning of human frailty. According to Paul, every individual lives with an inner struggle between good and evil. Even though Man is torn between good and evil, his value is immutable, in the same way that a banknote will have the same value irrespective of whether it comes directly off the printing press or whether it has become rumpled and worn.

Agape

Classical Greek uses two words for love: philos and eros. Philos is used for friendship, eros for sexual love. Both of these emerge from desires in a subject, an ego. Agape occurs as a neologism in The New Testament, and is used a total of 106 times in various inflections. This term emerges from desires in an object, a «you». In his description of agape, Paul makes his familiar statement:

«And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.» (2). Agape is not primarily associated with emotions or moods. It is action-oriented, directed towards others and has its source and ideal in God’s love of Man.

Practising love

Agape is demonstrated through the life and work of Jesus. The evangelist Luke, who was a doctor in the Hippocratic tradition, describes Jesus’ emotional reaction when seeing the funerary procession of a widow’s only son as splanchniste (English: heartfelt commiseration, strong empathy) (Luke 10). This describes an emotional reaction that grabs one’s innermost self.

Another radical element of the work of Jesus was the issue of who should be the object of this love. Who should be my concern? Jesus responds to this question with the parable of the Good Samaritan. Here, he expands the concept of «fellow man» to include all people, irrespective of age, gender, race, status and faith.

Historically, health and care have had a key position in the faith and practices of the church. Construction of hospitals followed the spread of Christianity, especially with the establishment of monasteries, and in later centuries through Christian missions in Asia and Africa. Diakoneo is the Greek word for serving, which was undignified to the Greeks. Deaconry was a separate, voluntary service in the congregations of the early church, consisting of supplying food and care to the needy. Remnants of this can still be found in our healthcare system, in the private, non-profit institutions we call diaconal.

Values in practice

Hardly any other professions are so frequently confronted with value-based problems as health workers, and to many, the choice of a medical career represents a deliberate value-based choice. Values form an implicit basis of each personal encounter between the patient and the doctor.

Reductionism

Various forms of reductionism may often be hard to see through. Reductionism reduces human complexities and makes humans smaller than they are (3).

Biological reductionism: Man is reduced to a purely biological being, a product of physiology and chemistry. You are your genes. You are what you eat. This is the fallacy of academic medicine.

Spiritual reductionism: Man is transcendent. Man is energy and is influenced by energies. You can rule your life by using your mind. This is the fallacy of the alternative movement.

Relational reductionism: Man is an independent individualist, unfettered and liberated – or the opposite, bound by authorities or the masses.

Health workers must resist this by rejecting all forms of reductionism and balancing the human being as a unity: a biological, psychological, spiritual and social being.

Values and choices

In our society, there is a broad consensus that medical treatment should be of equal quality and equally available to all, irrespective of money, position and power. To apply this thinking also in a global context, however, requires more of a stretch of the imagination.

In recent years, ideas and attitudes from the manufacturing industries have penetrated the healthcare services. Patients are turned into a commodity, services are subjected to competitive tendering, therapies are assessed on the basis of their cost and the social burden of diseases is estimated. This mindset can lead to a blunted view of human life and be a threat to core values (4).

The doctors of antiquity ruled over life and death, and were therefore regarded with suspicion (5). Hippocrates, and in a later era Christian teaching, broke away from this and introduced a strict distinction: The doctor’s duty was to heal, assuage and comfort – never to take life. Today, the ideals of absolute human value are challenged at both ends of life’s span. The real test of human value is not how long the healthcare services are able to keep a person alive, but the dignity with which every human is treated.

For aspiring doctors, the recognition of human nature as an arena for the struggle between good and evil is an essential insight into understanding themselves as well as their patients. The distinction is not one between the good and honourable on the one hand and the hopeless and intolerable on the other. Both aspects are found in every human being.

When people are affected by misfortune or disease, they are affected biologically, psychologically and relationally. Per Fugelli describes his experience of a broken ankle in very apt terms: «Suddenly you lie there without the tasks and illusions that block out the existential drama. Suddenly you are in a sort of laboratory of truth, where values and ways of living are put to the test. The disease turns into an existential crystallisation process, where everything transient, the things and the ornamentations fall away. What remains is the core of existence, what you believe in and the people you love» (6).

Health workers on a daily basis face a stream of people who are afflicted in body and soul. Few professions get to be familiar with the darker sides of life as frequently as the doctor: irrational acts, violence, conflicts, tragedies, self-destruction and mendacity. Our training has barely prepared us for this demanding daily situation. Time constraints provide little room for reflection and thought. Some choose to place their values and doubts on the shelf, and carry out their daily work in an instrumental and steadfast manner. Others think that staying within the boundaries of laws and regulations and satisfying the authorities’ norms of acceptability is what matters most.

Summing up

A bridge must be constructed between the ethical challenges involved in medical practice and the values that have been passed on to us through our culture and faith. In this manner, the doctor can preserve a personal integrity and protect patients from abuse. Core Christian values that have passed the test of time form a basis for facing future challenges. Raising awareness, through building consensus and proving their relevance, is necessary in order to make values more than just high-sounding words.