HIV/AIDS activism in the USA emerged as a reaction to discriminatory tendencies in society in general and the handling of the epidemic in particular. The activists made a lasting impact on biomedical research. In a world where conservative movements are on the rise, we can learn from these activists’ fearlessness.

Activists demonstrating against high costs of the AZT drug in front of the New York Stock Exchange on 14 September 1989. Photo: AP/Tim Clary/NTB scanpix

On the morning of 14 September 1989, Peter Staley sneaks into the New York Stock Exchange. Dressed as a businessmen with a forged visitor’s badge, he and some other members of the activist organisation ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) make it to the balcony of the trading hall to which they handcuff themselves. Just before nine-thirty, when trading starts, they unfurl a banner saying ‘SELL WELLCOME’, with reference to the Burroughs Wellcome pharmaceutical company which holds the patent for AZT (azidothymidine). The sound of the bell that normally marks the start of trading is drowned out by the activists’ hand-held megaphones. This delays the start of trading for several minutes, a unique event in the history of the stock exchange. While this goes on, the activists scatter leaflets saying ‘We die while you make money. Fuck your profiteering’.

Nearly 1 500 demonstrators gather in front of the stock exchange building in a demonstration coordinated with equivalent protests in London and San Francisco. The media coverage is extensive, with the exception of the New York Times, which for a long time chose not to cover the AIDS epidemic. Next day, the company cuts the price of AZT. For ACT UP, the organisation founded two years earlier, the campaign is a success. For Peter Staley it is also a personal victory. He had returned to the world of finance of which he once was part, but this time as an activist, an openly gay liberated man who was also HIV positive.

The scene is taken from the book How to survive a plague, written by David France and published last year. The author is also the originator of the 2012 film with the same title. The author addresses the AIDS epidemic in the USA from the first AIDS deaths in 1981 to the launch of effective treatment in the mid-90s. It is a personal narrative about the epidemic that struck an entire generation of gay men. It is a story of how healthy people, most of them in their twenties and thirties, were handed a death sentence. Many of them discovered their illness when dark spots appeared on their skin. Any such spots on somebody’s face made it clear to everybody that he was ‘one of those’ – like a return of the bubonic plague, with skin lesions rife with stigmatisation and shame. Kaposi’s sarcoma also represented society’s first encounter with the disease that in 1982 received the designation AIDS. Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals was the headline of a New York Times article on 3 July 1981. However, other groups were also profoundly affected, many of whom in marginalised populations, such as IV drug users, transgender people, people with haemophilia and people of colour.

Moral condemnation

In many ways, the HIV epidemic reinforced the tendencies towards stigmatisation that already existed in a number of Western countries, not only in the USA. In the UK, Thatcherism got the wind in its sails when a group of people who engaged in non-heterosexual sex were so explicitly affected. Among conservative politicians there was considerable opposition to the liberal sexual revolution and women’s liberation of the 1960s and 1970s, a development that threatened conservative values associated with the nuclear family and established gender roles. The HIV epidemic could be exploited for the purposes of this opposition. ‘Irresponsible’, sexually promiscuous gays became easy targets. As formulated by Kaye Wellings, professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: ‘We use deviants to reinforce the moral order (…) This is where the need for moral panic comes in. (…) With the advent of AIDS, I think there was a pent-up moral repression that needed expression. The AIDS scare was almost deliberately fanned. Every social institution was involved – the press, the Law, even the Church’ (1, p. 177).

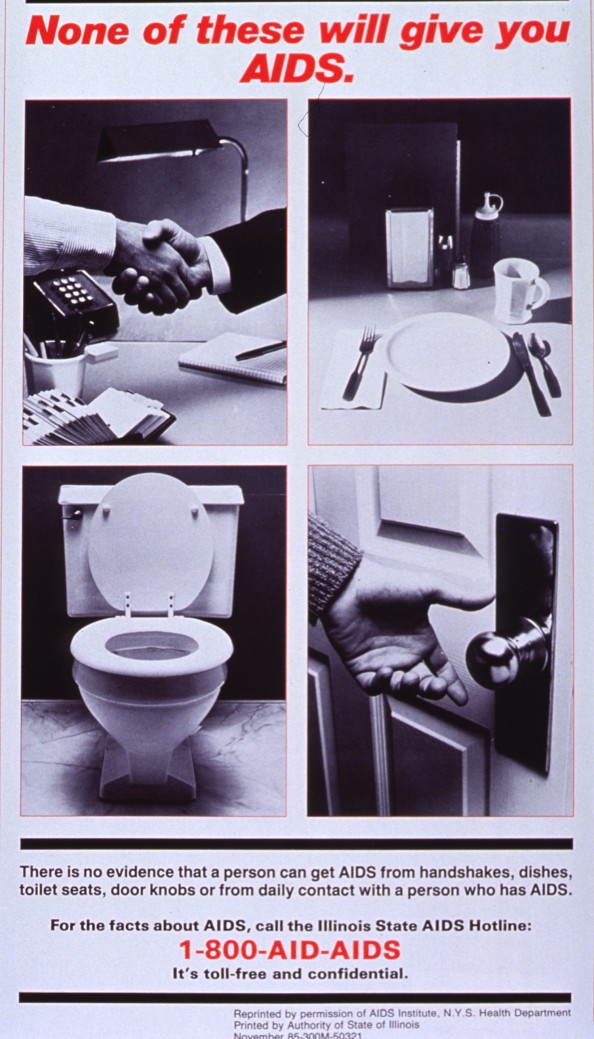

Public information campaign from 1987 that explicitly sought to calm the hysteria and combat stigmatisation Photo: Courtesy of the New York State Health Department

In Norway, the Church in particular took a moralising stance. For example, a prominent bishop referred to HIV as God’s punishment, without the Church taking exception to his statement. The most stringent demands for coercive measures tended to come from the most conservative people (2). The distribution of clean syringes to prevent the spread of HIV among IV drug users was also controversial, among politicians as well as the police. This measure was seen as signalling that society accepted illicit drug use.

Destroyed gay lives

In the USA, discrimination manifested itself at several levels: although The New York Times published an early report in 1981, as referred to above, nearly two years passed and 600 deaths occurred before the issue appeared on its front page in 1983. Politicians also avoided placing the epidemic on the agenda, refrained from speaking about it in public and failed to allocate funds to address it. This included, for example, the mayor of New York, Ed Koch (1924 – 2013). France speculates as to whether Koch’s bachelor life in reality reflected that he himself was gay, which may explain his failure to address the crisis. It also included US President Ronald Reagan (1911 – 2004), who used the word ‘AIDS’ in public for the first time in September 1985 – after more than 6 000 people had died – whereas Vice President George H. W. Bush was criticised for his proposal to introduce mandatory HIV testing. In 1993, President Bill Clinton introduced a statutory ban on entry into the USA for foreign citizens who were HIV positive.

The book also narrates the story of the epidemic that transformed a city. Approximately 100 000 people died from AIDS in New York from the start of the epidemic until effective treatment was made available. For the gay movement in the 1960s and 1970s, free sex was explicitly used in the struggle for liberation from a heteronormative, sexist and oppressive patriarchal society. For example, rimming – oral-anal sex – was portrayed as a revolutionary act. The New York gay scene flourished, with a plethora of clubs, bars and saunas. HIV and AIDS killed not only people; an entire subculture was eradicated. Nobody remained unaffected. The days were filled with funerals. France describes a scene that occurred some years into the epidemic: ‘There was now a permanent line of wheelchairs outside the Village Nursing Home, where bony young men napped in the sun. The gay bars, which had been the teeming hub of gay society during his last visit, were now lifeless and ghostly places.’

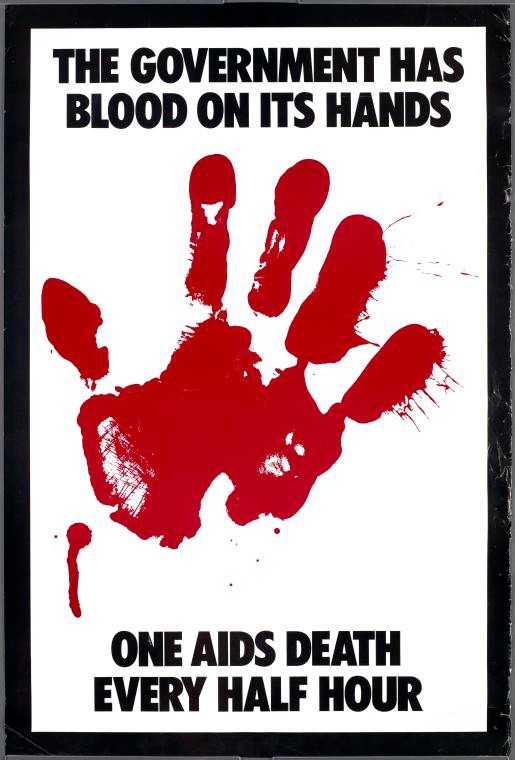

The epidemic united activists and artists in joint action leading to a series of creative campaigns. Gran Fury was one such collective, and in the words of Loring McAplin, a member of the group, its goal was: … ‘to fight for attention as hard as Coca-Cola fights for attention’. ‘Blood on Its Hands’ poster. Photo © Gran Fury

The HIV/AIDS epidemic was also a collective trauma for the gay movement, and the disease infiltrated sexuality by reinforcing internalised homophobia and shame of having non-heterosexual sex. For many, intimacy was made impossible for fear of contagion: Could you share a toothbrush with your lover? What about a lip sore, would a kiss cause infection? France describes how Staley’s partner felt after having taken a negative test: ‘Learning he was healthy made him feel unreasonably lucky, like a man still standing after five rounds of Russian roulette. He withdrew physically, sometimes too afraid to even kiss. Staley’s drives were similarly knotted up. The idea of sexual love was bound with death – with suicide and murder.’

Activism and courage

The book is also a story of resistance and struggle and of how a social movement can step in when society’s institutions fail. For example, the concept of ‘safe sex’ was invented by the HIV activists. In 1983, the activists Richard Berkowitz and Michael Callen (1955 – 1993) published the pamphlet How to have sex in an epidemic: one approach, with the guidance of the doctor Joseph Sonnabend. All of them were trendsetting activists. The point they made was that sex and love between men is not in itself risky; it is the way they have it. Promiscuity in itself should not be made an issue, only sex without a condom. The message came from people who were directly concerned. They knew ‘the lingo’ and where the shoe pinched.

This knowledge can be transferred to preventive harm-minimisation efforts in general: people need help where they are, not in light of our own notions of how they ought to live their lives, but by helping them to make the best possible informed choices. Studying a phenomenon on its own premises also makes it clear that practices and patterns of action often have explanations other than our first assumptions. In this sense, Benny Henriksson’s Swedish ethnographic study ‘Risk factor love’, published in 1995, was unique, in that he sought out gay men in places where they had sex, such as in the saunas (3). He showed that anal sex without a condom was a strongly symbol-laden act. For these men, dropping the condom was a demonstration of intimacy and love of their partner, i.e. an explanation quite different from the view that people who dropped the condom acted ‘irresponsibly’.

Many activists boycotted the AIDS conference held in San Francisco in 1990 because of the ban on entry into the USA for HIV positive persons. ACT UP was present, including Peter Staley (middle), and interrupted the final speech by Louis Sullivan, Minister of Health. Photo © Rick Gerharter

HIV/AIDS activism was gradually professionalised. The activists realised that to achieve influence, they needed not only to take to the streets, they also needed access to the boardrooms and a place at the table in the Food and Drug Administration, National Institute of Health, research groups and pharmaceutical companies. The activists needed to learn the language of the politicians and researchers, and they needed to understand virology, immunology and statistics.

It is striking to see the extent to which the story of HIV/AIDS activism is also an early narrative about user participation in research. The activists succeeded in portraying themselves as legitimate representatives of the test subjects – people with AIDS. They demanded not only drugs for all (‘Drugs Into Bodies’) and lower prices for these drugs, but also influence on the research process itself. For example, they were vehemently opposed to the testing of AZT in a placebo arm and not providing the drug to all patients with AIDS. The usual course of testing of the drug was circumvented, the Phase II study was terminated because of its promising results, and the drug was released to the market pending a final approval, due to the seriousness of the situation (also referred to as ‘compassionate use’) (4).

Dideoxyinosine (ddI) was introduced through a so-called ‘parallel arm’ to release the drug more rapidly to people with AIDS. This meant that the drug circumvented Phase II and III testing.

The issue is equally relevant today, for example in testing of experimental therapies for metastasised cancers: How do you explain to a patient with a death sentence that there is a 50 % chance that he/she will receive sugar pills? During the testing of AZT, the test subjects went out of their way to ensure that the drugs they took were active ones: they learned to taste the difference between placebo and AZT, they swapped pills with other study participants to reduce the risk of receiving only placebo, and they went to local laboratories to have the content of their capsules analysed.

In his study of the HIV epidemic, ‘Impure Science’ the sociologist Steven Epstein demonstrated the extent to which the credibility of the study results depended not only on the study and its results alone, but on the success of various stakeholders in presenting themselves as credible representatives or interpreters of research experiments (5). The HIV/AIDS epidemic thus helped change the way in which biomedical research is conducted, and especially the views on involvement of users in the research process. Frank Miedema, one of the founders of Science in Transition, an organisation that works for more transparency in the publication of research and increased user involvement, has stated that the HIV/AIDS activists made him realise the importance of user involvement in research – to enable the researchers to ask the right questions (6).

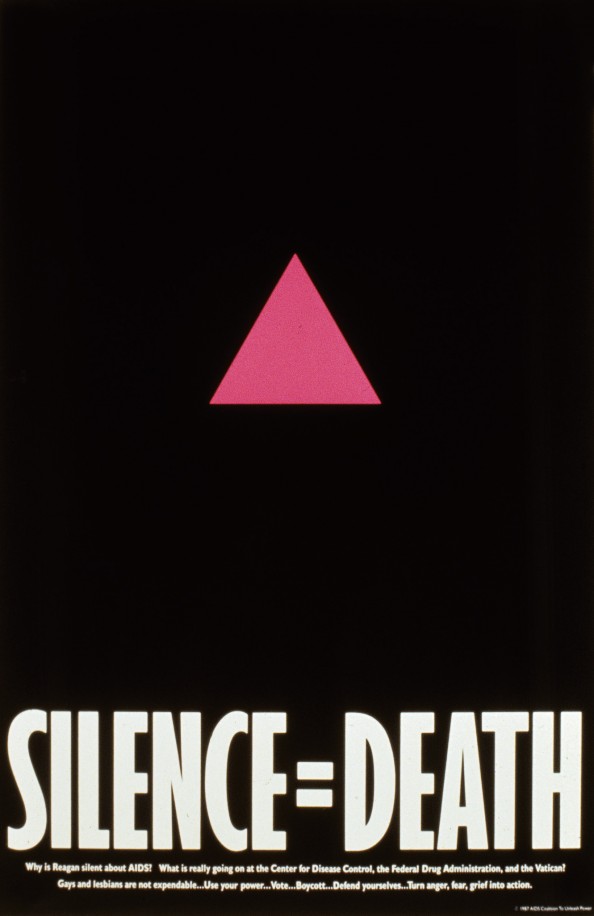

Iconic poster from 1987 made by Avram Finkelstein in the ‘Silence = Death’ artist collective. Consisting of graphic designers, the collective used visual effects to break the silence around AIDS. The pink triangle, which was used to mark out homosexuals in concentration camps in World War II, was used as a symbol of liberation by the LGBT movement in the 70s. Photo: Silence = Death Project

The activists questioned the gold standard of medical intervention research – the randomised, controlled trial – and showed how a series of normative assessments are made in all medical research, for example how study groups are composed. Thus, the activists succeeded in undermining the status of the randomised, controlled trial as representing an indisputable truth that was directly applicable to the real world.

A shared struggle

At first, the HIV/AIDS epidemic fuelled homophobia. Nevertheless, it gradually helped combat stigmatisation and increase tolerance for sexual diversity. For example, the epidemic has caused the media to discuss and speak more freely about condom use and non-heterosexual sex. Because people living with HIV came forward with a clear message (including in Norway), the disease acquired a human face. In the words of the historian Dagmar Herzog, the HIV epidemic thus cannot be regarded as the end of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 70s, but rather the opposite, since ‘the emergence of the disease and the fight to contain it were accompanied by ongoing sexual liberalization’ (1 p. 183).

Today, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has changed character, at least in high-income countries with well-established health services. HIV has become a chronic disease, and sufferers have normal life prospects if effective treatment is provided. Mother-to-child transmission can be effectively prevented. Distribution of clean syringes to IV drug users has meant that HIV is no longer an epidemic in this group, at least not in Norway. Globally, the HIV epidemic today most strongly affects countries in sub-Saharan Africa, where testing and access to treatment remain a major problem. Women, children, sex workers and men who have sex with men are particularly at risk. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia the epidemic is spreading, and there is a shortage of harm-reducing, preventive measures. In many parts of the world the epidemic thus continues to affect people unequally: discriminated and stigmatised groups are still the most vulnerable. In Norway, somewhat more than 200 people are infected each year, a little less than half of whom are men who have sex with men (7).

Henki Hauge Karlsen had HIV and lost his job as a bartender due to fear of infection. With his attorney Tor Erling Staff he took the case to court, and finally won in the Supreme Court in October 1988, giving him his job back. The judgment served as a strong legal precedent for the employment protection of persons who live with HIV. Some weeks later, Karlsen died at the National Hospital. He was the first person living with HIV to come forward publicly in Norway. Photo: Eystein Hanssen/NTB scanpix

Although medically speaking, HIV in Norway is to be regarded as an infection on equal terms with other chronic diseases, it is still shrouded in shame. In some gay communities, the current discussion about drug-based HIV prevention – pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) – has been seen to cause a return to a moralistic line of argumentation. Again, criticism is raised against promiscuous behaviour, in characterising people who seek to protect themselves against HIV as ‘irresponsible’. The term ‘Truvada whore’ was born, named after the drug Truvada, which to date is the only drug approved for the indication of pre-exposure prophylaxis. FRI – the Norwegian Organization for Sexuality and Gender Diversity – and the HIV Norway association have followed up this topic with panel discussions. This shows that the activist organisations continue to play a key role in preventive efforts.

The history of HIV and AIDS in the USA showed that the epidemic reinforced certain repressive tendencies in society. For example, some feminist activists pointed out that fertile women are often excluded from clinical studies out of a fear of teratogenic effects of the drugs, which has meant that specific AIDS complications only seen in women, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, were not recognised as AIDS-related illness. However, the history of HIV/AIDS activism in the USA showed that activist movements themselves may help reinforce repressive mechanisms. In the late 80s and early 90s, ACT UP activists pointed out that the organisation gave priority to the challenges faced by gay white men, at the cost of women and non-whites.

The activists of the 1980s nevertheless show that social movements have the potential to unite for a common cause when it comes to, for example, women’s rights, anti-racism and HIV activism. We last saw this in the ‘Women’s March’ on 21 January this year, in the context of Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration. Then, the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) organisations joined forces with the women. Recently, some feminists have sought to portray the struggle for the rights of transwomen as conflicting with a feminist project. This is groundless; we should all rather join the struggle for the rights of all women.

A relevant book: David France. How to survive a plague. London: Picador, 2016

There are numerous recent examples of right-wing extremist groups that have sought to espouse the LGBT cause and use it to promote anti-immigration and islamophobic policies. They claim that Islam is a threat to a broad diversity of sexualities and gender expressions in society. The argument is hollow, since it ignores the fact that Muslims themselves are often victims of discrimination in today’s society, not least gay and lesbian Muslims. History has shown us that the conservative forces stood on the wrong side of the HIV/AIDS struggle. The history of HIV/AIDS ought to inspire the activist organisations to stand shoulder to shoulder in the promotion of minority rights.