Kafka’s short story The Metamorphosis reminds us of our vulnerability and how we may all find ourselves alienated.

Illustration: Tony Miller

‘One morning, as Gregor Samsa was waking up from anxious dreams, he discovered that in bed he had been changed into a monstrous verminous bug.’ This is the first line of the famous short story The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka (1). The insect scenario in the story is absurd, but appeals to a general human fear: what if I should fall ill, what if I should find myself excluded, what if I suddenly should become unable to earn a living? From being the son and main breadwinner in a family of four, Samsa is transformed overnight into ‘ein ungeheures Ungeziefer’, a monstrous verminous bug.

Samsa feels like his old self but is physically changed, and others see him as different and repulsive. His family shows no empathy or interest, and lacking any language that others can understand, he is left alone with his thoughts, ending up terribly lonely in a corner of his own house. At first, his sister provides him with some food, then only leftovers, and finally he barely eats anything, fades away and disappears.

Alienation

Differentness, exclusion and empathy (or lack of it) are key topics both in this text and in our society. In addition, it also elucidates an obvious injustice: Samsa has done his best while working as a travelling salesman, and his family has profited from it. When he is no longer able to do his job, he has no value. The cynicism of his next of kin knows no bounds, and finally they wish him dead. It brings to mind the old person who stays in a nursing home bed for most of the day against their will, the child who suffers from complex disorders and receives inadequate medical treatment, or the seriously mentally ill person who has waited months for therapy. Samsa was just an ordinary man. Change and misfortune may strike anybody. Some of us end up on the street, others struggle with addiction.

In parallel, the symbolism of the text points to something that resonates with us: what if I should suffer the same fate, fall seriously ill, be changed, no longer be able to fend for myself? Kafka presents a horror scenario in which nobody cares.

Empathy and differentness

Empathy is derived from the German word ‘Einfühlung’, which gradually came into use in the 19th century, originally a term to describe obtaining an increased understanding of art (2). The term is composed of the Greek en, which means ‘in’, and pathos, ‘feeling’ or ‘suffering’, in other words ‘in-feeling’: the ability to vicariously experience somebody else’s thoughts and emotions (3). The word makes a key point: that we are both participants and spectators at the same time, both inside and outside, as we are when we read The Metamorphosis.

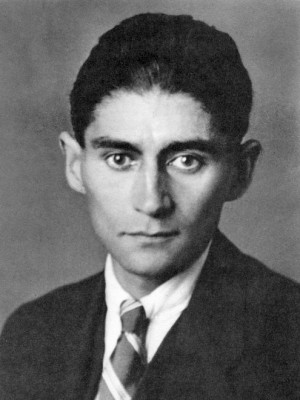

Franz Kafka in 1923. Photo: Wikimedia commons

Kafka (1883–1924) grew up in a middle-class, German-speaking Jewish family. Although conscious of his family background, he considered himself an outsider to Jewish culture. At one point he declared himself an atheist and started attending socialist meetings. In his final years, however, he took a growing interest in Jewish culture and language (4–6). As a member of a minority and with antisemitism on the rise, he learned what belonging to a stigmatised group feels like. Public debates on eugenics and racial hygiene were already taking place long before the turn of the century, and in his final years, Kafka considered moving to Palestine.

Kafka wished to spend his time writing, but he needed to obtain an education for a profession that could earn him a living. After studying law, he worked long days in an insurance company, leaving him little time to write. His days were spent on earning a living; this was what gave him worth in the eyes of his family. He finally contracted tuberculosis, causing his throat to swell up. He was unable to take any sustenance and died in 1924, at the age of only 40 years (4–6).

An insect turns into a human

In Haruki Murakami’s short story Samsa in Love, the metamorphosis is turned on its head in a scenario which is just as absurd as Kafka’s. An insect wakes up one morning and finds itself turned into Gregor Samsa (7). One might think that most things would work out, but as a human, Samsa is just as uncertain, excluded and perplexed as before. He is afraid to venture outside, sexually confused and out of control. The text is both tragic and humorous. Understanding the world and trying to ‘fit in’ is no simple matter for anyone.

‘It is at the time when we need it most that we long for someone who meets our helpless gaze, comes close to us and wishes us well. No matter whether the trouble is cancerous cells, heroin or a cerebral stroke, we need a national soul that has been nurtured to provide care and not exclude, to understand and not judge,’ Per Fugelli wrote (8). Literature reminds us of our vulnerability and our shared responsibility for each other.