Emergency primary health care units are at their busiest during the Easter and Christmas holidays (1). It is more difficult to get an appointment with a GP during holiday periods. Also, many patients are away from home, staying in municipalities where they are not resident. Calling in at the local accident and emergency unit is therefore the only option available to them.

However, although the Christmas break is generally a busy time in emergency units, some days are busier than others. As the spirit of Christmas is meant to bring peace to one and all, there would be reason to believe that our emergency units enjoy the same bliss. But most emergency care doctors who have been on duty on New Year’s Eve will have found that by then, the peace of Christmas is well and truly over.

There is little knowledge available about the work of emergency primary health care units in Norway over the festive period (2). The objective of this study was to identify the volume of injuries and psychosocial problems that occur on Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve, and to compare these figures to a normal Saturday.

Material and method

The material comprises data obtained from all electronic reimbursement claims submitted by doctors on out-of-hours duty in Norway in the period 2008–18, previously used to compile the annual statistics for the emergency primary health care service (1). Anonymised computer files were obtained from the KUHR database (Control and Payment of Reimbursement to Health Service Providers) held by the Norwegian Health Economics Administration.

Consultations and home visits (tariff codes 2ad, 2ak, 2fk, 11ad and 11ak, hereafter referred to as ‘consultations’) were recorded for Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve and the last Saturday of January (3). Saturday was chosen because it is followed by a non-working day, the same as Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve. GP surgeries are therefore closed and patients directed to the emergency primary health care unit instead of waiting for GP surgeries to open the next morning. The last Saturday of January was chosen because this is a period with no special celebratory events, and in order to enable comparisons to be made for the same time of year.

The variables used were the time of contacting the service, diagnostic codes (ICPC-2) and tariff codes. Times of contacting the service were grouped in the categories of daytime (12.00–17.59), evening (18.00–23.59) and night-time (00.00–05.59). In order to enable valid comparisons to be made, mornings before 12 noon were excluded, because many GP surgeries are open until noon on Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve, but not on Saturdays. Night-time was defined as the hours after 12 midnight on 24 or 31 December, or the early hours of Sunday morning. In the interest of securing robust and stable figures, numbers for the years 2008–2018 were added up to form a total. Injuries are defined and categorised in accordance with the Norwegian Institute of Public Health’s report on accidents and injuries in Norway (4).

The annual statistics for the emergency primary health care service were assessed by the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration’s data protection officer and by the Data Protection Official for Research (1). Because it is impossible to identify individuals on the basis of the material, be it directly or indirectly, the project is not subject to the notification requirements imposed by the Norwegian Personal Data Act.

Because the material comprises all the electronic reimbursement claims rather than a sample, the differences demonstrated are real and not encumbered by statistical uncertainty. The data are therefore presented without confidence intervals, and no statistical tests have been conducted.

Results

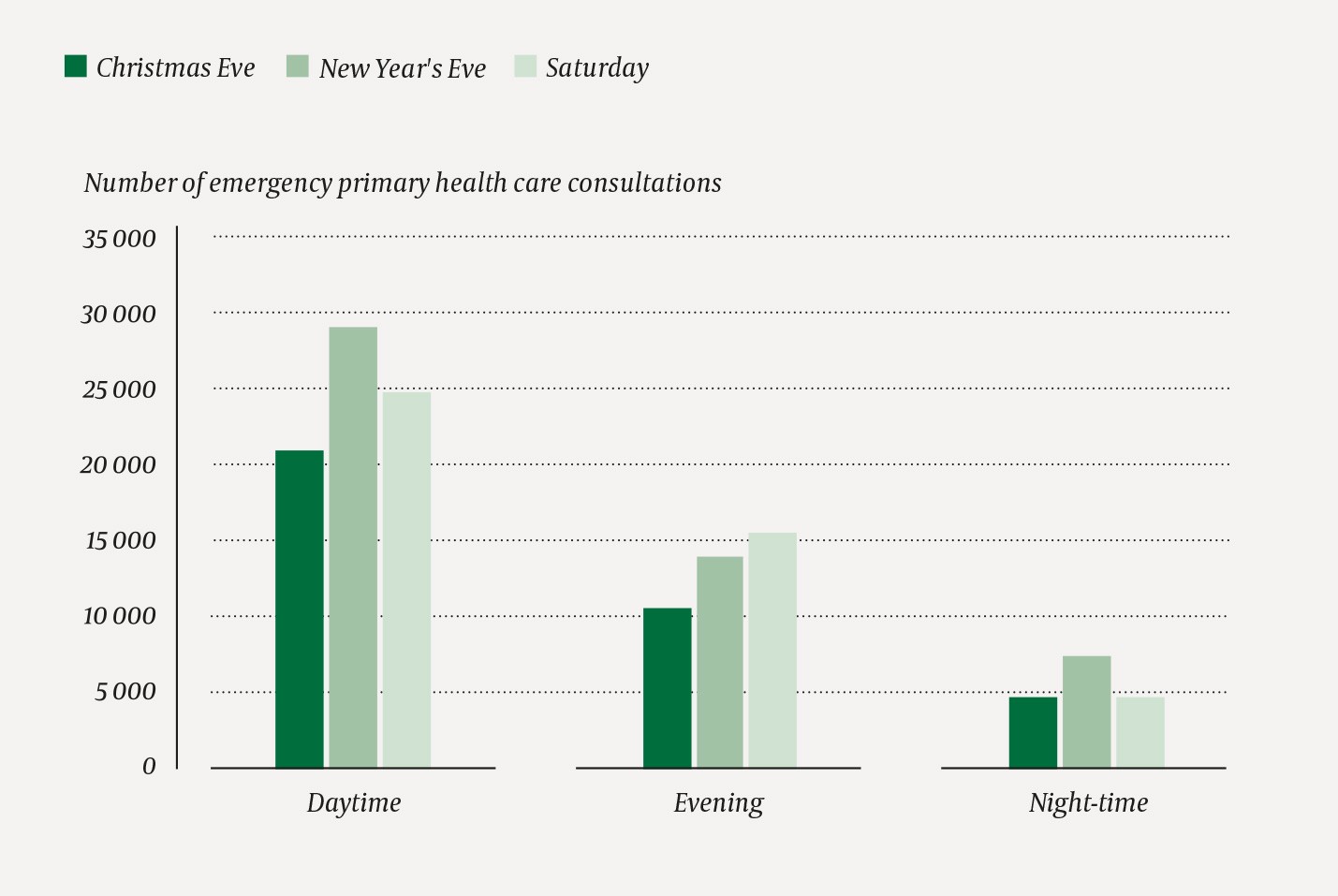

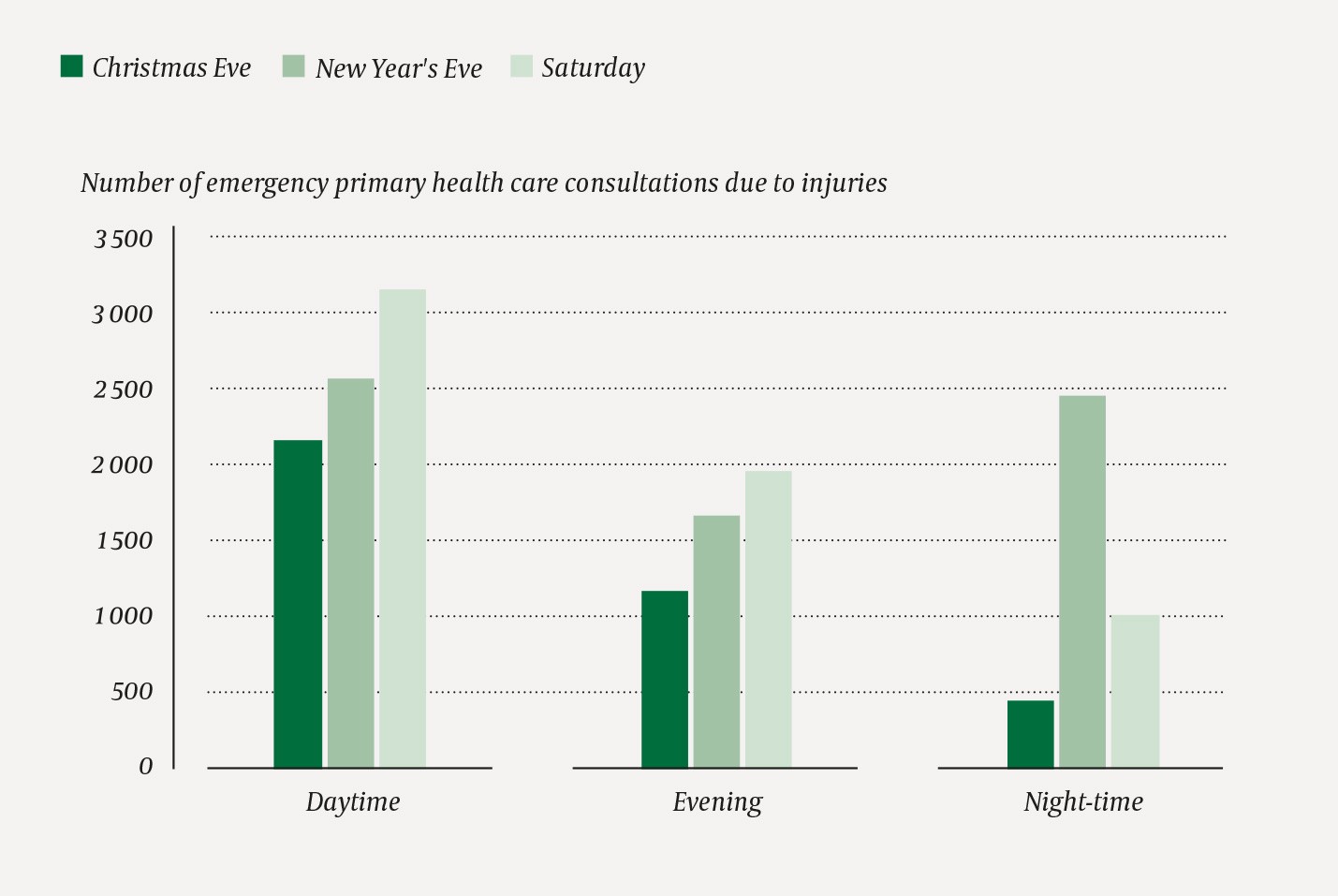

On Saturday, there were 45 088 consultations in total. The same figure for Christmas Eve was 36 045 (80 % of Saturday) and for New Year’s Eve 50 377 (112 % of Saturday) (figure 1). Saturday night-time saw 1 007 consultations due to injuries. The same night-time figure for Christmas Eve was 453 (45 % of Saturday) and 2 447 for New Year’s Eve (243 % of Saturday) (figure 2).

Figure 1 Number of consultations and home visits by emergency primary care doctors on Christmas Eve (N = 36 045), New Year’s Eve (N = 50 377) and the last Saturday of January (N = 45 088) for the years 2008–18. Daytime refers to the hours between noon and 17.59, evening refers to the hours between 18.00 and 23.59, while night-time refers to the hours between midnight and 05.59 the following morning.

Figure 2 Number of consultations and home visits by emergency primary health care doctors due to injuries on Christmas Eve (N = 3 778), New Year’s Eve (N = 6 675) and the last Saturday of January (N = 6 107) for the years 2008–18. Daytime refers to the hours between noon and 17.59, evening refers to the hours between 18.00 and 23.59, while night-time refers to the hours between midnight and 05.59 the following morning.

Table 1 shows the distribution of consultations stemming from various types of injury. There was significant over-representation of all types of injury overnight on New Year’s Eve. There were 246 night-time consultations due to burns on New Year’s Eve. The corresponding figure for Christmas Eve was 13 (5 % of New Year’s Eve night-time) and 11 for Saturday (4 % of New Year’s Eve night-time). There were 120 night-time consultations due to eye injuries on New Year’s Eve. The corresponding figure was 16 for Christmas Eve (13 % of New Year’s Eve night-time) and 23 for Saturday (19 % of New Year’s Eve night-time).

Table 1

The number of consultations and home visits by emergency primary health care doctors due to various injuries distributed between Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve and the last Saturday of January for the years 2008–18. Daytime refers to the hours between noon and 17.59, evening refers to the hours between 18.00 and 23.59, while night-time refers to the hours between midnight and 05.59 the following morning.

|

Types of injury,

ICPC-2 diagnostic codes

|

|

Christmas Eve

(N = 3 778)

|

|

New Year’s Eve

(N = 6 675)

|

|

Saturday (N = 6107)

|

|

|

Daytime

|

Evening

|

Night-time

|

|

Daytime

|

Evening

|

Night-time

|

|

Daytime

|

Evening

|

Night-time

|

|

Fractures

L72, L73, L74, L75, L76

|

|

260

|

86

|

50

|

|

394

|

134

|

205

|

|

494

|

184

|

86

|

|

Strains, sprains and dislocations

L77, L78, L79, L80, L81, L96

|

|

331

|

120

|

60

|

|

605

|

224

|

239

|

|

795

|

391

|

120

|

|

Head injuries (excl. fractures), concussion

N79, N80

|

|

142

|

58

|

41

|

|

167

|

101

|

236

|

|

247

|

168

|

164

|

|

Eye injuries (incl. foreign bodies)

F75, F76, F79

|

|

118

|

49

|

16

|

|

109

|

82

|

120

|

|

175

|

127

|

23

|

|

Penetration injuries, stings, cuts, bites

S13, S18

|

|

769

|

523

|

161

|

|

725

|

587

|

973

|

|

801

|

631

|

399

|

|

Burns, scalds

S14

|

|

114

|

85

|

13

|

|

100

|

182

|

246

|

|

84

|

84

|

11

|

|

Other surface injuries, incl. insect stings

S12, S15, S16, S17, S19, H78

|

|

168

|

82

|

31

|

|

201

|

123

|

121

|

|

232

|

139

|

70

|

|

Poisoning

A84, A86

|

|

34

|

26

|

31

|

|

39

|

47

|

145

|

|

47

|

52

|

53

|

|

Other injuries

A80, A81, A88, B76, B77, D79, D80, H76, H77, H79, N81, R87, R88, U80, X82, Y80

|

|

214

|

146

|

50

|

|

216

|

192

|

162

|

|

266

|

183

|

81

|

|

Sum total

|

|

2 150

|

1 175

|

453

|

|

2 556

|

1 672

|

2 447

|

|

3 141

|

1 959

|

1 007

|

Mental problems, suicide/attempted suicide, alcohol intoxication and social problems were also over-represented overnight on New Year’s Eve (table 2). There were 513 night-time consultations due to acute alcohol intoxication on New Year’s Eve, while the corresponding figure for Christmas Eve was 53 (10 % of New Year’s Eve night-time), and 260 for Saturday (51 % of New Year’s Eve night-time). There were no significant differences between Christmas, New Year’s Eve and Saturday with respect to fatalities.

Table 2

The number of consultations and home visits by emergency primary health care doctors due to a selection of health problems, distributed between Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve and the last Saturday of January for the years 2008–18. Daytime refers to the hours between noon and 17.59, evening refers to the hours between 18.00 and 23.59, while night-time refers to the hours between midnight and 05.59 the following morning.

|

Health problem (ICPC-2 diagnostic code)

|

|

Christmas Eve (N = 1 694)

|

|

New Year’s Eve

(N = 3 486)

|

|

Saturday (N = 2 534)

|

|

|

Daytime

|

Evening

|

Night-time

|

|

Daytime

|

Evening

|

Night-time

|

|

Daytime

|

Evening

|

Night-time

|

|

Fatalities (A96)

|

|

105

|

89

|

21

|

|

95

|

91

|

22

|

|

112

|

77

|

10

|

|

All mental health problems (P)

|

|

527

|

432

|

299

|

|

725

|

656

|

1 013

|

|

575

|

622

|

615

|

|

Acute alcohol intoxication (P16)

|

|

15

|

34

|

53

|

|

22

|

68

|

513

|

|

29

|

55

|

260

|

|

Suicide/attempted suicide (P77)

|

|

20

|

13

|

23

|

|

32

|

35

|

69

|

|

15

|

32

|

36

|

|

All social problems (Z)

|

|

21

|

18

|

24

|

|

30

|

31

|

84

|

|

26

|

20

|

50

|

|

Sum total

|

|

688

|

586

|

420

|

|

904

|

881

|

1 701

|

|

757

|

806

|

971

|

Discussion

In emergency primary health care units, Christmas Eve is a little more peaceful than a normal Saturday, while New Year’s Eve is marred by alcohol intoxication, mental health problems, injuries, suicides/attempted suicides and social problems. There is no doubt that New Year celebrations carry a health risk.

Many visits to emergency primary health care units are not caused by acute illness, and it is often fine to see how things progress for a while. Some patients may choose to sit it out at home rather than disturb the family harmony at Christmas. A wait-and-see attitude may contribute to the low volume of emergency unit consultations on Christmas Eve. However, the incidence of fatalities is the same at Christmas, New Year and on a normal Saturday.

International studies suggest that there are generally fewer instances of psychiatric illness and suicides at Christmas (5, 6). In Austria and Sweden, the suicide statistics for Christmas Eve are low, but high for New Year’s Eve (7, 8). In Norway, the incidence of mental health problems is also lower at Christmas than at New Year. It is easy to surmise that Christmas bliss in the bosom of the family has a protective effect. Christmas get-togethers are also often organised for those who would otherwise have spent the evening alone (9).

New Year celebrations on the other hand are characterised by alcohol and antisocial partying that may well trigger mental health symptoms. Overnight on New Year’s Eve there was also significant over-representation of poisoning, and it is reasonable to assume that other intoxicating substances than alcohol were contributing factors. Another reason for the over-representation of mental health problems at New Year may be the effect of broken promises, with the Christmas holiday perhaps not living up to expectations (7, 8).

Eye surgeons have long been warning against the risk of eye injuries caused by careless handling of fireworks in connection with New Year celebrations (10). This study suggests that there is a severe rise in all types of injuries at New Year, but the relative increase is greatest in respect of eye injuries and burns. There is every reason to believe that this is linked to private firework displays, and whether such displays should continue to be lawful must be a timely question.

Conclusion

Christmas Eve is peaceful in emergency primary health care units. New Year’s Eve on the other hand, is probably the worst night of the year. A ban on private firework displays may reduce the extent of injuries.