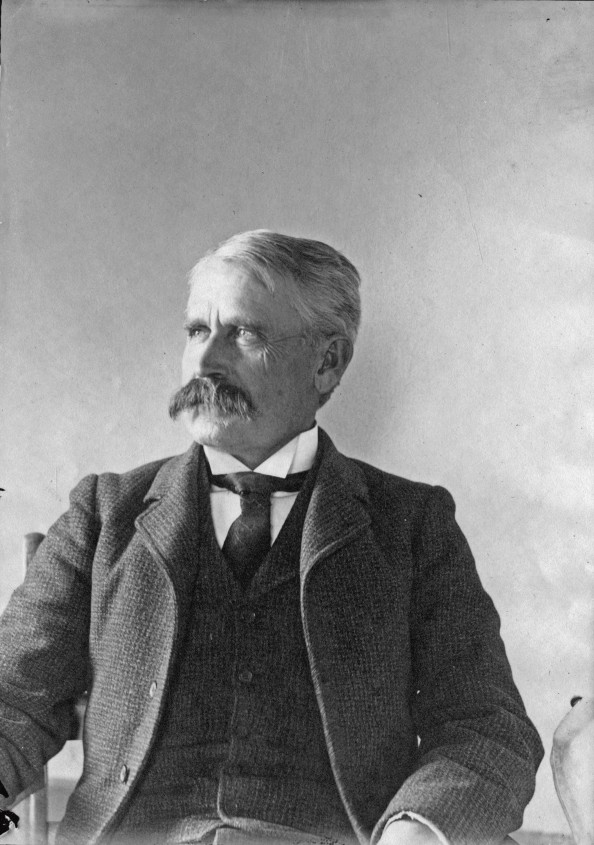

James R. Walker (1849–1926) was a doctor and public health champion, ethnographer and folklorist. His work brought him into close contact with religious leaders and ‘medicine men’ from the indigenous American population. He was trained and inducted as a shaman of the Lakota Nation. Do we, the ‘medicine men’ of the modern world, have anything to learn from their spirituality, shamanism and social practices?

James Riley Walker worked for many years as a doctor on Native American reservations in the Midwestern United States. His public health efforts to combat tuberculosis were remarkable, and he was trained and accepted as a shaman and ‘medicine man’. Photo: Stephen H. Hart Research Center, History Colorado.

James Walker was born in a log cabin in Illinois in 1849 as the oldest of ten children (1). Before he turned 15, he enlisted to serve in Illinois’ Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. After catching dysentery, he received a medical discharge on grounds of illness and returned home. He went on to pass his medical degree examination in 1873. He ran a practice in his home town for a few years before embarking on a long career as a medical practitioner to various Native American reservations in the Midwest. For the first few years, he worked on the Chippewa Tribe Reservation in North Minnesota. In the winter of 1882/83, the reservation was plagued by a smallpox epidemic. In freezing temperatures, Walker worked heroically to provide care and to quarantine those who were ill, while ensuring that healthy people in the area and in neighbouring districts were vaccinated. He was later honoured for his efforts by President Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919).

As the administrative head of the Chippewa Reservation, one of Walker’s responsibilities was to control drunkenness, criminality and destructive disorderliness in the community. He fought against powerful forces such as whisky pushers. In a particular confrontation with these men, he took an authoritarian stance, took recourse to a firearm and wounded a Native American with a stray bullet. This could have ended up with reciprocal fire, which would have put Walker’s life at risk. The episode lost him the trust of the indigenous population and he had to leave his job.

For a couple of years, he ran a practice in the North-East, in the state of Washington, but there are few known written sources from this period. It was his work on the Pine Ridge Reservation of South Dakota from 1896 onwards that made Walker a renowned clinician, public health champion, ethnographer and folklorist. This was where he improved and modernised medical practice among a population of almost 7000 people, of whom 4983 were full members of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) Tribe (1).

Public health work to combat tuberculosis

When Walker arrived on Pine Ridge, there was a high incidence of tuberculosis, which impacted heavily on the population’s mortality rate. At the time, it was a widespread view that half the Lakota Tribe were sick with tuberculosis. Walker’s epidemiological surveys showed that this was a great exaggeration (2). He found that only 741 of the 4983 tribe members on the reservation had tuberculosis, which is a prevalence of 14.9 %. The annual death rate for the disease was 2.5 %, almost half the total mortality rate. The birth rate was too low to compensate for the high mortality, so the net annual population loss was 1.2 %.

He worked together with the shamans and learnt about their practices and their notions of disease. In return, he taught them about his own understanding and about evidence-based thinking

Walker vigilantly observed the sociodemographic causal factors for the large increase in the incidence of the disease. Like other indigenous people on the prairies of the Midwest, the Lakota Tribe had lived a nomadic existence in well-aired tipis. The open fireplace served as a ‘spittoon’, and the tent skins were well aired and cleaned after relatively short periods of encampment in each place. Tuberculosis had occurred among them since time immemorial, but never had the incidence been as high as after they were forced to take up permanent residence in overcrowded houses with no ventilation and poor sanitary conditions (2).

George Sword (Long Knife), here in 1909, was James Walker’s close friend and teacher. He was a shaman, member of the Bear medical society and the leader of armed troops and hunting parties. Sword converted and became a deacon to the Christian church on Pine Ridge (8). Photo: Joseph Kossuth Dixon / Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

However, Walker’s preventive public health work was clearly based on the so-called contagionist view that disease was caused by a contagious agent. He found that the prevalence of the disease correlated with social and sanitary conditions. His public health strategy was, however, based on his observations of infection: everyone who had been infected, had – without exception – been in contact with people who suffered from tuberculosis. ‘If this infecting material [in the sputa of consumptives and the discharge from scrofulous sores] is prevented from coming in contact with the uninfected, tuberculosis will be prevented,’ he wrote (2). He achieved this by moving the sick out of the overcrowded houses and isolating them in resurrected tipis where they benefitted from an abundance of fresh air and sunshine. Saliva and pus were destroyed so that no uninfected individuals were exposed. Within five years, the prevalence of tuberculosis fell from 14.9 % to 10.5 %. The mortality rate was almost halved (2). When a colleague on the reservation quit his job, Walker was the only doctor left. Clinical work had to be prioritised in an area the size of the state of Connecticut, and it became harder to focus on public health. The prevalence increased once again, but not to the same level as in 1896. Walker suggested to the authorities that a sanatorium be built for tuberculosis patients. These plans were eventually realised.

Ethnography and folklore

Walker’s public health work would have been impossible had he not first won the trust of the indigenous population, their leaders and their holy men. He had been working as a doctor among Native Americans for almost 20 years and had set himself the goal of getting to know them from their own perspective. He worked together with the shamans and learnt about their practices and their notions of disease. In return, he taught them about his own understanding and about evidence-based thinking. He even managed to dye tubercle bacilli and show them the disease causative agent under a microscope (1). This was presumably a new realisation that was difficult to take on board.

Walker was a public health pioneer in that he recognised the importance of user involvement and an integrated health service that accommodates people’s spiritual needs

Walker’s folklore studies included observations and interviews with the reservation’s eldest, but were primarily associated with the training he received as a shaman. Although earlier anthropological studies of the Lakota Tribe did exist, Walker admirably managed to understand their symbolism, myths, songs and creeds, thereby providing a comprehensive presentation of the culture. In order to qualify as a shaman, he had to go through the four levels of the Sun Dance. This gave him an insight into and experience of the tribe’s spirituality (4). This work brought him into contact with several shamans and professional storytellers. One of his most important teachers was a shaman by the name of George Sword, who had converted to the Christian faith and served as deacon to the congregation on Pine Ridge.

According to Walker, the Lakota saw themselves as unique and superior to others (4). Fellow human beings who did not accept this view were considered enemies. The degree of kinship was judged by several hierarchical criteria, and there were special rules to prevent intermarriage. In order to acquire a woman, a man had to pay her family a certain quantity of buffalo skin clothing. If he was unable to get a wife in this way, he would either have to steal a woman from another tribe or accept whoever was offered to him. In such a scenario, and if the woman had no tipi of her own, he owed the woman a debt of gratitude and had to build her a tipi before their first child was born. It was the wife who owned the hides of any buffalo her husband felled while hunting. The meat was shared out amongst everyone in the camp. She was also the owner of the tipi and had the authority to make decisions within the family (1, 4).

The third day of the Sun Dance, painted by Short Bull in 1912. Illustration: The Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History (item 50.2/4063).

In other words, the marriage contract did not depend solely on the consummation of a sexual relationship; it was only recognised once the husband had secured his wife’s social standing. Women had a position in society and enjoyed a number of rights, but the man’s masculine power meant that his wife, and sometimes her younger sisters, were his property (4, 5).

In modern western society, we have lost the understanding that health depends on spirituality

By taking part in tribal life, Walker gained an insight into a hierarchically structured society where there were clear distinctions between the different groups of Lakotas as well as internally within each group. Only trusted men gained a seat on the tribe council, but they were replaced according to specific procedures and after specific periods of service. Leaders, and particularly shamans, had significant authority bestowed on them. On the other hand, people had considerable autonomy in choosing whether or not to belong to a group. The leaders enjoyed extensive power, but if they failed to serve the interests of the people, their fall would be from a considerable height. Shamans who abused their power for personal gain could be punished by death (4).

A meeting of religions

Walker arrived on Pine Ridge six years after the massacre at Wounded Knee, which is a stream that runs through the Pine Ridge Reservation. In this massacre, soldiers from the 7th Cavalry Regiment, the same regiment that suffered a humiliating defeat at Little Bighorn in 1876, had opened fire against unarmed ghost dancers. They killed 250–300 men, women and children. Walker talked to eye witnesses who gave detailed descriptions of the massacre. His account of Wounded Knee, in the words of the indigenous population, form a part of Eli Ricker’s tablets, a collection of interviews with survivors from the wars with the indigenous population (6). Black Elk, a Lakota Tribe holy man, is reported to have said that human beings were not the only fatalities at Wounded Knee; the dream of a better world that until then had been alive among the indigenous population had also died (7).

During the colonisation of the North-American Continent, the most severe loss suffered by the indigenous population and the whites alike was perhaps the inability of the ‘palefaces’ to understand the nature-religious values of the Native Americans. Christianity was not infrequently promoted by suppressive means, accompanied by a ban on the indigenous population’s religious rites (Box 1).

Box 1 Religious rites

The religious rites were based on the belief that all things in nature were animate. Human beings could get help by attaining spiritual contact with an animate universe. The most important rites were purification by steam in sweat lodges (cleansing and strengthening the body by inhaling the water’s soul), striving for visions (solitary meditative existence in order to receive signs and revelations from the spiritual world), pipe-smoking (ceremonial contact with the spirit world through inhalation of soul power from tobacco and certain herbs) and the Sun Dance (dancing and singing for several days in order to gain strength and recognition from the sun and from the community).

Walker did not only recognise the values of the Lakota Tribe, he also joined their religion by training as a shaman. His efforts may have been commendable (from a public health perspective), but he was accused by colleagues on Pine Ridge and by the local congregation of bringing medical science and Christianity respectively into disrepute (1).

Did he believe in the existence of spirits and in the rituals’ appeasing effect on them? According to Walker himself, it was the nature-religious aspects of the Lakota faith that fascinated him, and he found that their rituals could have a healing effect on people’s suffering. He was accepted as a shaman primarily because the tribe’s own shamans were old and few in numbers, and they recognised that this might be their only opportunity to pass on their religion to their descendants (8).

Walker went far in his recognition of the shamans’ supernatural powers and believed that they manifested a universal human capacity to gain insight into the mysteries of nature beyond the sense of man (8). Nevertheless, it is important to point out that he also defended science. For instance, he exposed how some shamans were using trickery to remove worms that were supposedly the cause of tuberculosis (1).

The balance is currently shifting from the avoidance of discomfort and pain to living a self-respecting life in accordance with one’s own values

The ecumenical movement among people of faith around the world gained pace only a couple of generations after Walker’s death, with the 21st ecumenical council (the Second Vatican Council) in 1965 being one of several turning points. This was also to become a source of inspiration for conciliatory talks between Native American religious leaders and Catholic priests on the reservations of South Dakota (9).

Seven years of talks developed mutual respect and recognition that there were common functional elements in the rituals of the two religions that might appear dissimilar to an outside gaze. For example, purification by steam in sweat lodges may well fill the same religious need as the confession and forgiveness of sins. Prayer and meditative practices are akin to one another, and revelations are equally important in both religions (9).

Of course, the talks also revealed that there were differences. It was hard to agree on the existence of spirits and the appeasing effects of rituals. Even if Christianity has established the Holy Spirit as an intermediary between human beings and God, Christians expect no causal connection between rituals and the appeasement of a spirit that helps us as we go about our daily lives. However, causal explanations were of very little interest to the Native American religious leaders, who were more concerned with effects and functionality. Also, the Lakota people had no concept of sin. They were more concerned with shame, and how they handled shame through improvement rituals and, if required, through social exclusion (9).

The fourth day of the Sun Dance, painted by Short Bull in 1912. The Sun Dancer had to demonstrate endurance and tolerance to self-inflicted injury. The four levels of the Sun Dance determined social positions. The fourth level (dancing like a shaman) gave the highest social rank of shaman, spiritual leader and holy man (1, 5). Illustration: The Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History (item 50.2/4064).

An attitude to life that we might learn something from?

Walker was a public health pioneer in that he recognised the importance of user involvement and an integrated health service that accommodates people’s spiritual needs. Although the importance of supporting and recognising such needs is well documented in western medicine, spiritual care remains an ad hoc activity in medicine, exclusively available to individuals who express a need for such care (10). The Lakota Tribe saw medicine in a spiritual cultural context, where all human healing and learning depended on contact with the spirits of nature.

In modern western society, we have lost the understanding that health depends on spirituality (10). The secular contract that was established in western societies after the wars of religion in the 17th century, has also represented a barrier to the integration of spiritual care and healing in techno-medical science (11).

I draw inspiration from Knud E. Løgstrup (1905–81). To me, he is a ‘modern-day Red Indian’ in that he rediscovered a nature-religious position to which religious creed is irrelevant. Løgstrup’s religious thinking and his philosophy of sensation represent an attitude to life which expresses an ancient wisdom which has long been supressed. Our senses put us in immediate touch with our experience of what is ‘out there’. This can fill us with gratitude precisely because it does not depend on our own efforts, only on our ability to open up to what we receive, without prejudice and predetermined categories. We can take pleasure in visual, audio and sensory impressions by immediately being in the company of what we sense. This is a basic premise of life that takes precedence and that enables us to choose to live every morning without reflecting on and weighing up the pros and cons. This is the nature of the munificence of the world and of creation (12, 13).

This attitude to life is now emerging in western culture, albeit from an outsider position. In medical and psychotherapeutic practice, the balance is currently shifting from the avoidance of discomfort and pain to living a self-respecting life in accordance with one’s own values. Nature can educate us through presence in meditative practices and value-congruent actions (14). The Lakota people’s Sun Dance is a ritual for the advancement of cultural core values: courage, generosity, strength and integrity. These are values we share with them.