Thyroid nodules are common. As a result of increased use of diagnostic imaging, more nodules are detected as incidental findings. The great majority of them are benign and need no treatment. Systematic ultrasonography performed by a skilled doctor, possibly combined with cytology sampling, will to a large extent determine which nodules require follow-up.

Thyroid nodules are common. As a result of increased use of diagnostic imaging, more nodules are detected as incidental findings. The great majority of them are benign and need no treatment. Systematic ultrasonography performed by a skilled doctor, possibly combined with cytology sampling, will to a large extent determine which nodules require follow-up.

Thyroid nodules are a common clinical problem. Epidemiological studies have shown the prevalence of palpable nodules in adults to be about 5 % in women and 1 % in men (1). Thyroid nodules will be detected in 19–68 % of randomly selected individuals examined with high-resolution ultrasound (1).

For clinicians and radiologists lacking experience in thyroid diagnostics, the investigation and evaluation of thyroid nodules can be challenging. We would like to recommend a procedure for the targeted investigation of thyroid nodules based on the ‘Norwegian national plan of action with guidelines for the investigation, treatment and monitoring of thyroid cancer’ [Nasjonalt handlingsprogram med retningslinjer for utredning, behandling og oppfølgning av kreft i skjoldbruskkjertelen] published in 2017 (2), as well as recent international literature and our own experience.

Most thyroid nodules are benign (87–95 %) (3). The aim of investigation is to identify the small group of patients with thyroid cancer, while avoiding unnecessary testing of patients with benign nodules. A good medical history and palpation by the examining doctor are essential aspects of the clinical evaluation.

All referrals for diagnostic imaging must include details of the medical history and the clinical examination (Box 1). In the rare cases where there is a strong suspicion of cancer, the patient should be referred directly to the oncology clinical pathway in the specialist healthcare service (Box 2).

Box 1 Clinical information that would form a basis for referral for ultrasonography of the neck

Medical history and clinical assessment of cancer risk

Previous radiotherapy of the head or neck

Family history of thyroid cancer

Age under 18 years or over 70 years (especially in men)

Rapid growth of a nodule

Clinical examination with findings upon palpation

Hard consistency, fixed lesion, palpable lymph nodes (see red flag symptoms in Box 2)

Persistent dysphonia (hoarse voice), dysphagia or dyspnoea (see red flag symptoms in Box 2)

Blood tests

TSH, free thyroxine (fT4), free triiodothyronine (fT3), antibodies against thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) and serum calcium (possibly calcitonin)

Box 2 Symptoms and findings that require prompt investigation and referral to the oncology clinical pathway (2).

Child (under 18 years) with thyroid nodule

Radiological findings, molecular findings or cell changes revealed through fine-needle cytology

Most patients with a clinically or radiologically detected thyroid nodule are referred for a targeted ultrasound examination at a hospital or X-ray unit. Depending on the results of this examination, it may be decided that the investigation is complete (benign radiological findings) and that the patient requires no further testing or ultrasound follow-up. Referral for another ultrasound examination is recommended only if new symptoms (Box 1) or red flags (Box 2) appear. It should be clear from the description of the ultrasound findings whether there is a need for further investigation with ultrasound-guided fine-needle cytology (FNC). If this is required, the patient should be referred to a centre where this can be performed.

The skill level of the doctors who perform the initial ultrasonography can vary greatly. If the results are inconclusive, for example because of suboptimal ultrasonography or because there is no possibility of fine-needle sampling, the patient must be examined again and if appropriate referred to a specialist centre for interdisciplinary assessment and treatment. In the last five years, we have registered an increase of around 50 % in referrals for interdisciplinary assessment at our centre of expertise at Oslo University Hospital.

In recent decades, there has been an increase in the number of cases of thyroid cancer in Norway, and in 2018 there were 408 new cases (294 women and 114 men) (4). Mortality in cases of thyroid cancer is stable. The median age at diagnosis was 54 years in the period 2014–18, and has been virtually unchanged since 1984 (4). Increased use of diagnostic imaging has contributed to more cases of thyroid cancer being detected. Most cancerous nodules are carcinomas with a good prognosis (5). Metastases account for only 0.2 % of malignant thyroid tumours identified through routine diagnostics (5), and are mainly detected and managed by the specialist healthcare service.

Modern ultrasound diagnostics, when performed correctly, are able to distinguish potentially malignant nodules from benign ones to a high degree. Given a satisfactory cytological specimen, a sufficient degree of diagnostic certainty can usually be achieved to allow the next steps to be decided. It is important that the person performing the ultrasonography has experience and expertise in evaluating thyroid nodules. An increased focus on training in thyroid ultrasound diagnostics, as well as the establishment of centres with the capability of performing ultrasound-guided fine-needle cytology, and possibly the presence of a screener (bioengineer) or cytologist during sampling, could enable more patients to have their thyroid nodules classified during their first ultrasound examination. Some institutions in which the cytopathologists themselves perform the ultrasonography and any accompanying sampling, achieve high levels of accuracy (6). However, this requires adequate staffing levels of cytopathologists with experience in ultrasound.

The routine use of standardised templates for reporting the results of ultrasonography and cytological evaluation can contribute to a more reliable diagnosis (7). An overall assessment of clinical findings, ultrasonography and cytology results is used to determine the subsequent clinical pathway for the patient. Effective interdisciplinary collaboration between clinicians, radiologists and pathologists is essential for achieving the most reliable diagnosis possible, and is of great help in clarifying cases where there is a discrepancy between clinical findings and findings from ultrasonography or cytology.

Diagnostic imaging

Ultrasound is the most appropriate imaging modality for assessing and characterising thyroid nodules and can reveal whether fine-needle cytology is indicated. Patients who have no risk factors for thyroid cancer should not undergo screening with ultrasound. Nor is routine use of ultrasound recommended in cases of hypo- or hyperthyroidism. Ultrasonography of the neck should be performed if a patient has palpable nodules, increasing nodular goitre, enlarged lymph nodes on the neck, or if there is clinical suspicion of a malignant lesion. If the patient has symptoms or discomfort related to the thyroid gland, the clinician must decide whether the patient should be referred for ultrasound.

A normal thyroid gland is well-defined with a homogeneous echostructure on ultrasound. In adults, the length of each lobe is usually 4–6 cm and the width/thickness up to 2 cm. Normal thyroid volume in women is 10–15 ml and in men 12–18 ml (8). The size and location of a thyroid nodule must be described as part of its evaluation. The echogenicity, shape, margins, calcification and vascularisation of the nodule as well as any signs of growth outside the thyroid should also be carefully described. If the patient has multiple nodules, each must be evaluated.

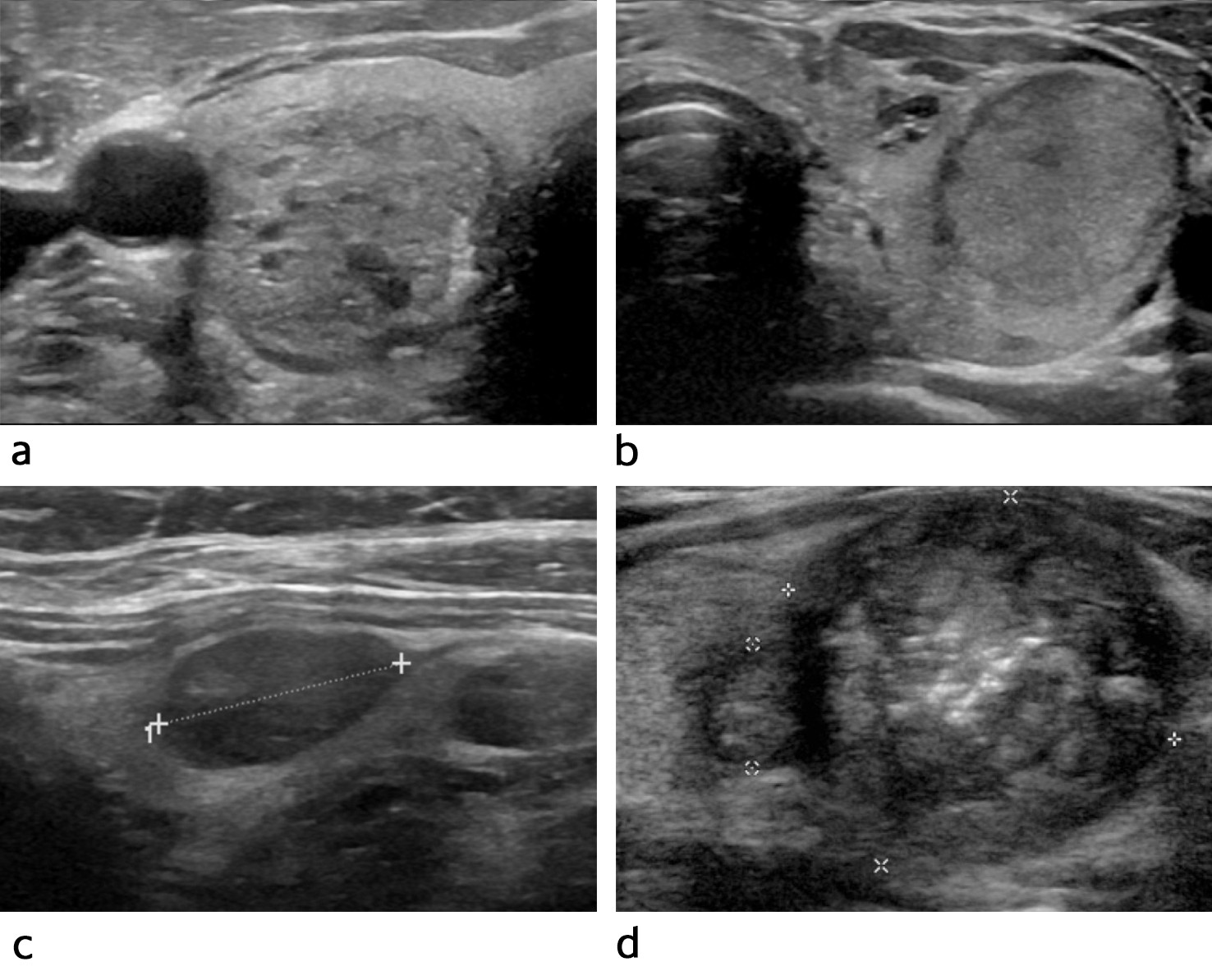

A typical benign thyroid nodule has a cystic or spongiform appearance, is well-defined and has an oval shape (Figure 1a). If the patient has several uniform and well-defined nodules in an enlarged gland, these are usually benign and do not require further cytological testing. Ultrasonography is performed only if symptoms or red flags arise (Box 2).

Figure 1 Typical ultrasound findings for different thyroid malignancy risk categories (TIRAD = Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System). a) The nodule is oval, well-defined and spongiform. Its characteristics suggest it is benign (TIRAD 2). b) The nodule is oval, well-defined and isoechoic. There is a low risk of cancer (TIRAD 3). c) The nodule is oval, well-defined and moderately hypoechoic. There is a moderate risk of cancer (TIRAD 4). d) The nodule has irregular margins, contains microcalcifications and has a markedly hypoechoic periphery. There is a high risk of cancer (TIRAD 5).

Thyroid nodules suspected of being malignant are often solid and hypoechoic, have irregular margins and an irregular shape and may contain microcalcifications (Figure 1d). These nodules must be examined further with fine-needle cytology.

If thyroid cancer is suspected, the entire neck must be examined with ultrasound to determine whether there are any lymph node metastases. A pathological lymph node in the neck can be the first sign of thyroid cancer (9).

In the United States and several European countries, reporting systems (7, 10–12) based on ultrasound criteria are used to grade the risk of malignancy. These systems ensure standardised descriptions of ultrasound findings and can improve communication between radiologist, cytologist and clinician. The American College of Radiology (ACR) uses the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TIRAD) for classification, inspired by the Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System (BIRAD). European guidelines recommend a variant of this system: EU-TIRAD (12). EU-TIRAD uses ultrasound criteria to place each nodule in a specific risk category. ACR-TIRAD is largely equivalent to EU-TIRAD (10, 13), but ACR-TIRAD calculates risk by summing the scores from several ultrasound criteria (13, 14). Within each risk group, the need for fine-needle cytology is indicated by the size of the nodule (Table 1).

Table 1

Criteria for classifying the risk of malignancy in the thyroid on the basis of ultrasound findings. The table shows the classification used by the American College of Radiology (ACR) and that used by the EU. The American classification system is based on points assigned in accordance with ultrasound findings regarding the nodules’ composition, echogenicity, shape, margins and echogenic foci. In the European system, findings are classified as shown in the table (10, 12, 13)). TIRAD = Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System. FNC = fine-needle cytology.

|

Category

|

Conclusion

|

ACR-TIRAD

|

ACR-TIRAD

Ultrasound points

|

EU-TIRAD

|

EU-TIRAD

Ultrasound findings

|

|

TIRAD 1

|

Normal, benign

|

No FNC / No follow-up

|

0

|

No FNC / No follow-up

|

No nodules

|

|

TIRAD 2

|

Not suspicious

|

No FNC / No follow-up

|

2

|

No FNC / No follow-up

|

Cystic, spongiform (mixed solid and cystic)

|

|

TIRAD 3

|

Low risk

|

FNC of nodule ≥ 2.5 cm

Follow-up if ≥ 1.5 cm

|

3

|

FNC of nodule > 2 cm

|

Oval

Well-defined

Iso-/hypoechoic

No high-risk features

|

|

TIRAD 4

|

Moderately suspicious / intermediate risk

|

FNC of nodule ≥ 1.5 cm

Follow-up if ≥ 1 cm

|

4–5

|

FNC of nodule > 1.5 cm

|

Oval

Well-defined

Moderately hypoechoic

No high-risk features

|

|

TIRAD 5

|

High risk

|

FNC of nodule ≥ 1 cm

Follow-up if ≥ 0.5 cm

|

7 and above

|

FNC of nodule > 1 cm

Follow-up/FNC if < 1 cm

|

At least one of the following high-risk features:

Irregular shape

Irregular margins

Microcalcification

Markedly hypoechoic and solid

|

The vascularisation status of an individual nodule is not included in the TIRAD criteria, but can provide important additional information.

TIRAD is a straightforward reporting system that can improve the quality of ultrasound examinations (Table 1, Figure 1). The system can also help to reduce overdiagnosis. We propose that EU-TIRAD should be used as standard for reporting the findings of thyroid ultrasonography. ACR-TIRAD is equally valid, however, and is also available as a simple online calculator (15). The report must specify which system has been used.

Scintigraphy has no place in the diagnosis of thyroid nodules. It should be performed only if the serum concentration of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is low, in order to detect (or rule out) a hyperfunctioning adenoma (2).

The American College of Radiology has prepared white paper guidelines (16) for nodules that are detected as incidental findings on CT and MRI scans. They recommend further examination with ultrasound of nodules larger than 15 mm in patients over 35 years of age or larger than 10 mm in patients under 35 (16). The Norwegian guidelines make the same recommendations (2).

PET-CT is routinely used in the investigation of multiple types of cancer. An incidental finding of increased uptake of FDG (fluoro-18-deoxyglucose) in the thyroid gland is associated with malignancy in around 30 % of cases (16). These patients should therefore be referred for ultrasound with fine-needle cytology (2, 16).

Ultrasound-guided fine-needle cytological sampling

Ultrasound-guided cytological sampling yields a higher percentage of specimens that are of sufficient quality for diagnosis than palpation-guided cytological sampling (17). Fine-needle cytology should therefore be performed with ultrasound guidance. The use of thin needles is recommended (25G or 27G, 0.46 mm and 0.36 mm in diameter, respectively) without aspiration. Exceptionally, a 23G needle (0.60 mm in diameter) may be used for cystic lesions. The use of ultrasound guidance ensures that the needle is inserted into the ‘correct’ nodule/lesion, and into the correct area of the nodule.

Cytopathological evaluation of thyroid specimens

A referral for cytological examination should include information on clinical findings and the ultrasonography findings. This is crucial for enabling the pathologist to properly evaluate the specimen, and for avoiding misinterpretation.

Cytological evaluation of fine-needle smears from thyroid lesions is performed in accordance with the international Bethesda classification system (18). The introduction of this classification has helped make the diagnoses given by pathologists more uniform, more consistent and easier for clinicians to relate to. The classification system was introduced internationally in 2010, and was updated and revised in 2017. Bethesda classification of thyroid cytology specimens was implemented in Norway in 2013–14. The classification system comprises six categories. Each category has a label and is numbered from 1 to 6, where 1 is an unsatisfactory specimen, 2 is probably benign, 3 is undetermined, 4 is neoplastic, 5 is suspicious for malignancy, and 6 is malignant. There may be subtle differences between laboratories in terms of how they classify cytological samples into the six categories, but the classification system seems to be well established among groups that assess thyroid lesions. The Bethesda classification system also describes the risk of malignancy for each of the six categories and provides specific recommendations for further management. This is useful for the doctors involved in the investigation. In Norway, experience has shown that too many specimens are non-evaluable (Bethesda category 1). Experienced doctors should perform the ultrasound-guided sampling to increase the proportion of specimens of sufficient quality for diagnosis (Bethesda categories 2–6) (18). Irrespective of who inserts the needle, it is useful for a screener or cytologist to be present when fine-needle sampling is performed, so that the quality of the specimen can be assessed immediately, so-called ‘rapid on-site evaluation’ (ROSE) (19). In our experience, close collaboration between the doctor who performs the examination (radiologist/clinician) and the screener/cytologist boosts the quality of the assessment.

Summary

Thyroid nodules are common, and the vast majority are benign. Ultrasound is the best imaging modality for evaluating thyroid nodules. To enhance the quality of ultrasound examinations and avoid overdiagnosis, we recommend targeted training of all those who perform thyroid ultrasonography. The doctor performing the ultrasonography should use a standardised reporting system (TIRAD). Fine-needle cytology should be performed with ultrasound guidance. The presence of a screener or cytologist helps ensure that a good quality specimen is obtained. Current practices for the investigation and treatment of thyroid nodules are dependent on close collaboration between clinician, radiologist and pathologist.