What does it feel like to undergo chemotherapy? And what are the implications of patient experiences for clinical research and professional practice?

This essay is based on a dialogue between two research colleagues. One of them had previously been ill with cancer; the other had not. One has a professional background in natural science and quantitative research, the other in humanistic and qualitative research.

Astrid was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014. Over a seven-month period, she underwent surgery, six rounds of chemotherapy and 15 radiation therapy sessions. Astrid and Hilde had five conversations in which they explored the various dimensions of cancer from both a subjective and a health science perspective. The conversations were recorded in an audio file and transcribed as text, which was then subject to a close reading and adapted into the text presented here. The text is written as an autoethnographic essay using the first person point-of-view (‘autoethnography’ has been defined as writing about one’s own experiences for a specific academic purpose’) (1, 2). It is Astrid that is the ‘I’ in the text.

Confusing emotions

My personal illness narrative began with a strong sense that something was wrong. It was as if I knew the diagnosis before it was made – cancer. My intuition turned out to be correct. An overwhelming, almost nightmarish scenario followed. A combination of confusing emotions, existential fear and despondency, as well as hope, a will to live and to be healthy again. I was 51 years old when I found a lump in my breast. A few weeks later I received the diagnosis. From then on, my life changed, yet I remained the same. I learned more about my own emotions and vulnerability, more about my own body, and not least, my experiences made me reflect on various aspects of my life and the encounter between me as a patient and health science professional and the medical and healthcare personnel who are so important in situations like mine.

It was as if I had disappeared from the world. Talking was impossible, and it felt like I was being swept away by a breaking wave

I was very nervous and restless before the chemotherapy. I pictured people with no hair who were thin, weak and pale. Before the treatment, I had so many questions that I ruminated over and that made me uneasy. How will it actually feel to have cytotoxic drugs in my veins? Could I have a heart attack as a side effect? How sick will I become and when? Will I feel well between the rounds of treatment? But I had no choice. I just had to pull myself together and jump in.

Side effects of fluctuating intensity

The chemotherapy took place in an outpatient cancer clinic at a hospital. I arrived in the morning and went home after the treatment – around midday. I usually had the same nurse during the treatments. She saw my uncertainty and my fear. When I met her, I immediately felt safe, and I put my complete trust in her from the first moment. If I became nervous about something during the treatment, she would quickly explain the situation to me. The treatment consisted of three small bags of liquid that was injected into my veins over a two-hour period. I went through this every three weeks in six rounds in the autumn of 2014.

The first treatment went very well, I thought. I did not notice anything, and I did not have a heart attack, which I had feared. I left the hospital feeling happy that day. Little did I know what the coming days would be like. The nurse said that I might feel unwell during the night, but if that happened, I should take extra anti-nausea medication. She also said that I might become a little constipated, and explained how I should deal with it. I forgot all of this the moment I left the hospital. In my joy of having survived my first treatment, I walked over to the bakery down the street. I was quite hungry and enjoyed some hot cocoa and sweet buns. They tasted incredibly good.

In many ways, my body took the reins; it gave orders, it made choices, and I hung on

Later in the afternoon I developed a slight headache, similar to when you sit for a long time in a room without fresh air. Then I started to feel unwell. Nauseous and shivering, I completely collapsed. It was as if I had disappeared from the world. Talking was impossible, and it felt like I was being swept away by a breaking wave. The entire first night was like this because I had not understood the forewarning of what was to come; I had not yet learned to take the anti-nausea medication in time.

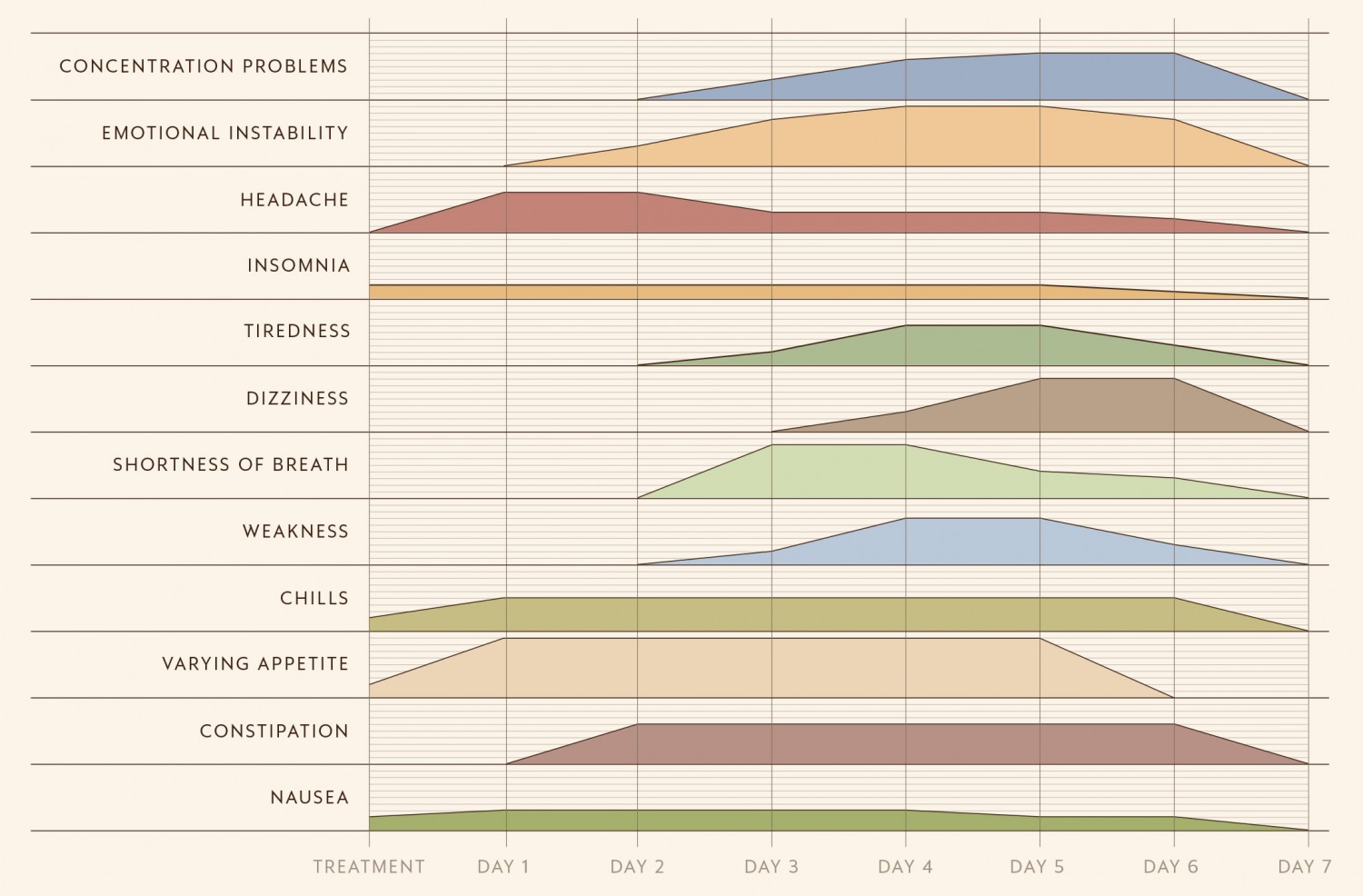

In the following days, I felt like my body was full of poison. Every day, the side effects changed and their intensity fluctuated. In the course of a week, I felt nauseous, chilled, constipated, dizzy, weak, tired and emotionally unstable. I had headaches, concentration problems, shortness of breath, insomnia and a varying appetite. Each side effect had a fixed day, and came and went at set times. On the first day of chemotherapy (day 0), nausea, headache and chills came over me slowly (almost like a hangover combined with morning sickness during pregnancy). I also had intense hot flashes, which lasted throughout the entire period of treatment but which have steadily subsided over time.

On the first day following the treatment, these side effects increased and my appetite changed. I was hungry, but I did not feel like eating. My body gave me a clear message about what it wanted and did not want with regard to food. Day 2 ran the same course, but with the addition of constipation, tiredness, concentration problems, shortness of breath and weakness. In the following three days I felt emotionally unstable as well. I was despondent, angry and fearful of seeing other people. I also had slight insomnia throughout the entire period. But on the morning of day 7 I was like a new person. I felt an abrupt shift from being sick to being well, which I had never experienced before in my life. It was not like having the flu, because then you recover gradually. I was suddenly well overnight. I was full of energy and vitality, but as it turned out this only happened after the first three treatments. Figure 1 shows my side effects from chemotherapy and their intensity throughout the first three treatments.

Figure 1 Side effects and their intensity relating to the first three chemotherapy treatments, day 0–7. The presence and intensity of the side effects are on a scale of 0–10, where 10 is the greatest intensity.

The period with side effects and challenges after each treatment proceeded in the same way during all six rounds of chemotherapy, but after the third treatment it took me longer to come around each time.

Because of this variability, I have begun to wonder if the methods we use in research and in clinical settings to measure these experiences capture them accurately

I had an incredibly powerful feeling that my body was in a field of tension between a sort of biological necessity and a subjective experience and that I had little control over how my days unfolded. In many ways, my body took the reins; it gave orders, it made choices, and I hung on. For instance, there were some kinds of food that I could not stand to see or smell while I was undergoing chemotherapy. I felt very ill when I saw yoghurt in the refrigerator. There were other foods, however, that I just had to have every day of the week during treatment, such as boiled cabbage with cranberry jam. In other words, my body was constantly sending out strong signals about what it needed and did not need. I interpreted this complete ‘takeover’ as having something to do with alleviating my symptoms. In the same way that my body governed my food intake, it also directed my need for fresh air and physical movement in order to ease my discomfort after treatment.

Back to daily life

Like many others with a similar disease profile, I underwent radiation therapy as an extension of the chemotherapy for a three-week period before I was declared ‘healthy’ and cancer free. At that point, I was supposed to try to return to my normal daily life, as I had lived before the diagnosis and as I had lived for many years prior. Paradoxically, I felt worse the day that the radiation therapy ended than when I received the diagnosis. In particular, side effects such as weakness, tiredness, concentration problems, hot flashes and emotional instability stayed with me between the treatments, throughout the period of radiation therapy and for five months after radiation therapy. It was not until one year after receiving the diagnosis that I felt healthy again and free from side effects. Today, five years after the cancer, I will soon finish my hormone treatment and annual check-ups with the cancer specialist. I feel well, and I cannot point directly to any sequela, only side effects from the hormone treatment. These I can easily live with.

Meta-reflection

This is my story, and of course I know that there are just as many stories as there are people who have gone through what I did. Some might recognise themselves in my experiences, while others will have completely different stories to tell about their symptoms and side effects.

How can a case like mine have value as a source of knowledge for research and professional practice? Will my story be too individual and anecdotal, or can it contribute insight that may benefit others?

We think it is also important to regard the patient as a knowledge source in a time of increasing emphasis on the evidence base for patient-oriented medicine and personalised treatment

As a researcher, I have worked for many years with patient experiences related to symptoms and health. This research field began in the 1990s in medicine, and a great deal of effort has been put into developing satisfactory questionnaires that patients answer in order to measure symptoms, side effects, functioning and general health. This used to be referred to as the measure of quality of life or health-related quality of life, but now this type of research falls under the umbrella of patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) (3).

My main impression, after having felt the side effects of chemotherapy, their complexity, variety, concurrence and predictability, is that the symptoms were experienced as intensely physical. Many factors varied through the treatment. The times and intensity of the side effects shifted. There was a continual fluctuation between the periods of time and days when I felt well and days when I felt sick. Because of this variability, I have begun to wonder if the methods we use in research and in clinical settings to measure these experiences capture them accurately, or if they instead give only a crude ‘imprint’ of the situation.

I was sent questionnaires while undergoing treatment, but I found them to be difficult to fill out. In order for health personnel to give good advice about how patients can live as well as possible during their treatment period, they need more nuanced information about how we as patients experience the side effects. This applies not only to information about which side effects we have and how strong they are, but also how they change over time and what we as patients can do ourselves to alleviate them.

The deep life questions related to a cancer diagnosis have been a part of Astrid’s experiences and our conversations. We do not mention them in this essay, however, because our purpose has been to give a systematic and nuanced experience-based description of the symptoms and side effects caused by chemotherapy. Very few such descriptions are found in the literature. Because Astrid has professional expertise in patient-reported outcome measures, she was able to write down her experiences in a combination of text and numbers. We think it is also important to regard the patient as a knowledge source in a time of increasing emphasis on the evidence base for patient-oriented medicine and personalised treatment. As such, it becomes relevant to ask how we can best gain insight into patient experiences and needs, both for research purposes and in clinical practice. We believe that existing methods for capturing patients’ voices can be enriched by more closely coalescing the scientific knowledge that currently forms the basis for patient reporting with a humanistic form of knowledge.