Abdominal pain and excessive vaginal discharge are common reasons why women of reproductive age present to the primary healthcare service or gynaecological outpatient clinics. The symptoms are often caused by sexually transmitted infections that are easily diagnosed and treated. In some circumstances, however, making the correct diagnosis proves far more challenging.

A woman in her early twenties was transferred to the gynaecological department from the gastroenterological department after admission due to abdominal pain and fever. She presented a 12-month history of symptoms (Table 1). For the first three of those months, she had been travelling in Southeast Asia, when she began to experience intermenstrual and postcoital vaginal bleeding while on oral contraceptives. She had been using oral contraceptives since the age of 16 and had a regular sexual partner at the time of symptom debut. Back in Norway, she consulted her general practitioner, but a gynaecological examination yielded normal findings. A cervical cytology sample was collected, along with specimens to test for gynaecological and sexually transmitted infections, but all tests were negative.

Table 1

Chronological summary of events and symptoms over each month of the disease course.

|

Month

|

Event

|

Symptoms

|

|

1

|

Travelling

|

Respiratory tract and genital symptoms

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

Return home from travels

|

Worsening of respiratory tract symptoms

|

|

5

|

|

Persistent genital symptoms

|

|

6

|

|

|

7

|

Rituximab infusion

|

|

|

8

|

|

Abdominal pain, urinary tract symptoms

|

|

9

|

Urological assessment

|

|

|

10

|

Gynaecological assessment

|

Purulent discharge

|

|

11

|

Admissions 1–3 (gastroenterological assessment)

|

Increasing abdominal pain and intestinal symptoms

|

|

12

|

Admission 4 (gynaecological assessment)

|

Signs of disseminated infection

|

In young, sexually active women who present with new-onset genital symptoms or altered bleeding patterns, sexually transmitted infections (including chlamydia) and cervical dysplasia should be considered (1). These conditions can usually be identified via a thorough medical history, gynaecological examination, and collection of cervical and genito-urinary samples for microbiological testing, plus cervical cytology samples. Many patients with sexually transmitted infections are asymptomatic however. There should therefore be a low threshold for obtaining samples for microbiological testing if the patient’s history includes unprotected sex. Untreated infections can cause long-term complications such as infertility and chronic abdominal pain (2).

One and a half years before the onset of genital symptoms, the patient had been diagnosed with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and had been receiving treatment with biannual infusions of rituximab (Table 1). During her three-month trip abroad, she had experienced recurrent respiratory symptoms, including a dry cough and dyspnoea, in parallel with the genital symptoms. While abroad, she received treatment with several oral antibiotic regimens with incomplete or no improvement. During the final month of her travels, she had persistent respiratory symptoms with purulent sputum. Shortly after her return home, a chest X-ray revealed basal pulmonary opacities, for which she received treatment with oral penicillin. This proved ineffective, and the treatment was therefore changed to erythromycin, which was effective. Chest X-ray five weeks later showed clear lungs.

At this point, the patient’s general practitioner had already begun to consider whether the chronic respiratory infection might be related to the immunosuppressive drug rituximab. A neurologist was consulted, who requested outpatient blood tests. These showed leukocytes 8.4 · 109/L (reference range 3.5–11.5 · 109/L) with a normal differential count, platelets 317 · 109/L (165–387 · 109/L), CRP 30 mg/L (< 5 mg/L), CD19 B cells 0.0 · 106/L (88–581 · 106/L), CD4 helper T cells 372 · 106/L (516–1 494 · 106/L), serum (s)-IgM 0.19 g/L (0.30–2.30 g/L), s-IgG 7.19 g/L (6.00–15.3 g/L), s-IgG1 5.84 g/L (5.2–12.7 g/L), s-IgG2 0.68 g/L (1.43–5.60 g/L), s-IgG3 0.20 g/L (0.28–1.05 g/L), s-IgG4 0.33 g/L (0.08–1.04 g/L), complement factor C3 1.18 g/L (0.83–1.65 g/L) and complement factor C4 0.35 g/L (0.13–0.36 g/L). The B-cell depletion and hypogammaglobulinaemia were regarded as anticipated effects of rituximab. No changes were made to the biannual rituximab infusion schedule. However, due to the patient’s vulnerability to infection, the neurologist noted that it might be worth considering a longer rituximab dosing interval or a different immunotherapy.

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that causes targeted B-cell depletion that can persist for several years and also give rise to hypogammaglobulinaemia (3). The immunosuppression thus increases the risk of respiratory tract infections caused by opportunistic microbes (3).

The patient received her scheduled rituximab infusion seven months after the onset of symptoms (Table 1). One month after the last infusion, she developed constant pain in the lower abdomen and dysuria. The urine was cloudy with intermittent macroscopic haematuria, and she experienced urinary urgency and involuntary urination. There was never growth of urine pathogens, only normal genitourinary bacterial flora and, after several unsuccessful attempts at antibiotic treatment, the patient was referred to a urologist. However, the results of cystoscopy, CT urogram and urodynamic testing were all normal. At this point the patient had had symptoms of infection from the lungs, genitalia and urinary tract for nine consecutive months.

Nearly 75 % of patients with multiple sclerosis report bladder dysfunction (4). The most common symptom is urinary urgency, which is due to impaired inhibition of detrusor contraction. Up to 50 % of patients report intestinal dysfunction. Dysfunction of bladder and bowel musculature often occurs alongside motor dysfunction in the lower extremities (4).

Ten months after the onset of intermenstrual bleeding and respiratory symptoms, the patient developed purulent vaginal discharge (Table 1). She was referred to a gynaecologist, who observed yellow discharge and inflammation of the vaginal mucosa. The gynaecological examination was painful, and microbiological tests for gynaecological infections were negative.

Eleven months after the onset of symptoms, the patient experienced gastrointestinal symptoms including blood and mucous in stools, alternating diarrhoea and constipation, weight loss of 4 kg in three weeks, nocturnal hyperhidrosis and febrile episodes (Table 1). This resulted in three hospital admissions. Upon the first admission, the patient had mild tenderness in the lower left quadrant. Blood tests showed leukocytes 12.2 · 109/L and CRP 28 mg/L, but a CT scan of the abdomen was normal. She showed spontaneous improvement and was discharged the following day with a referral for outpatient colonoscopy. She was then readmitted 24 hours later due to pain, and was again discharged the following day as the pain subsided. The third admission took place four days later. Examination revealed tenderness in the upper abdomen, and she was assessed for possible inflammatory bowel disease. Faecal calprotectin was slightly elevated at 150 µg/g (< 50 µg/g) but colonoscopy showed normal mucosa in the terminal ileum and colon. The biopsies from the terminal ileum showed non-specific changes; the colon biopsies were normal. An ultrasound scan of the abdomen including the liver and biliary tract, CT scan of the abdomen, and MRI of the small intestine were normal. The patient was discharged with an outpatient appointment scheduled for one month’s time.

There was no clear indication that the patient suffered from inflammatory bowel disease, as neither endoscopic nor radiological changes were present. The histological findings were non-specific, with only a slight increase in faecal calprotectin. The symptoms of Crohn’s disease are abdominal pain, diarrhoea (with or without blood admixture), weight loss and fatigue (5). Symptoms involving the internal genitalia may occur as a result of abscesses in the lesser pelvis or as a result of fistulation. Enterovesical fistulae give rise to recurrent urinary tract infections; enterovaginal fistulae to intestinal gas or faeces per vaginam. Fistulae occur in 15–50 % of patients with Crohn’s disease, with half being perianal and a quarter enteroenteral. The remaining fistulae are of other origin including gynaecological (6).

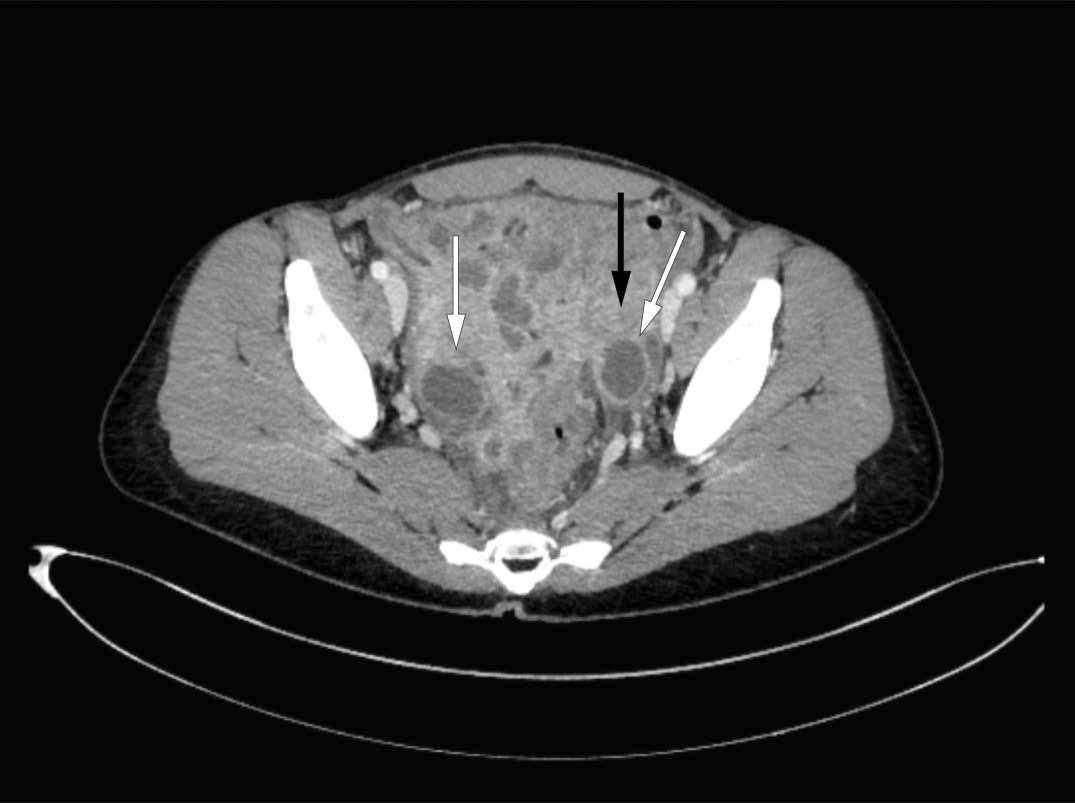

The patient was admitted for the fourth time in four weeks, with increasing abdominal pain, fatigue, signs of infection and organ dysfunction. Twelve months had now passed since the onset of symptoms. She presented with an elevated respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min, a temperature of 38.5 °C, tachycardia of 100 beats/min and blood pressure of 106/64 mm Hg. Examination revealed pronounced palpation and rebound tenderness in the lower abdomen. Blood tests showed leukocytosis 17.9 · 109/L with an excess of neutrophilic granulocytes 15.6 · 109/L (1.7–8.2 · 109/L), a high CRP level of 200 mg/L and elevated biliary parameters with s-ALP (alkaline phosphatase) of 178 U/L (35–105 U/L) and s-GGT (gamma-glutamyltransferase) of 159 U/L (10–45 U/L). Antibiotic treatment with piperacillin and tazobactam was started due to suspicion of an intra-abdominal abscess. A gastroenterologist performed an ultrasound scan of the abdomen, focusing in particular on the intestines and pelvic area, and detected changes in both adnexa and thickening of the wall of the sigmoid colon. A CT scan of the abdomen, which included the lesser pelvis, showed bilateral ovarian abscesses (Figure 1). Blood and urine cultures taken upon admission showed no growth. Serological testing was negative for hepatitis A, B and C, HIV and syphilis. The Quantiferon-TB Gold test for tuberculosis was also negative.

Figure 1 CT scan showed marked inflammation in the pelvis with enlarged, fluid-filled ovaries (white arrows) and thickening of the wall of the sigmoid colon (black arrow).

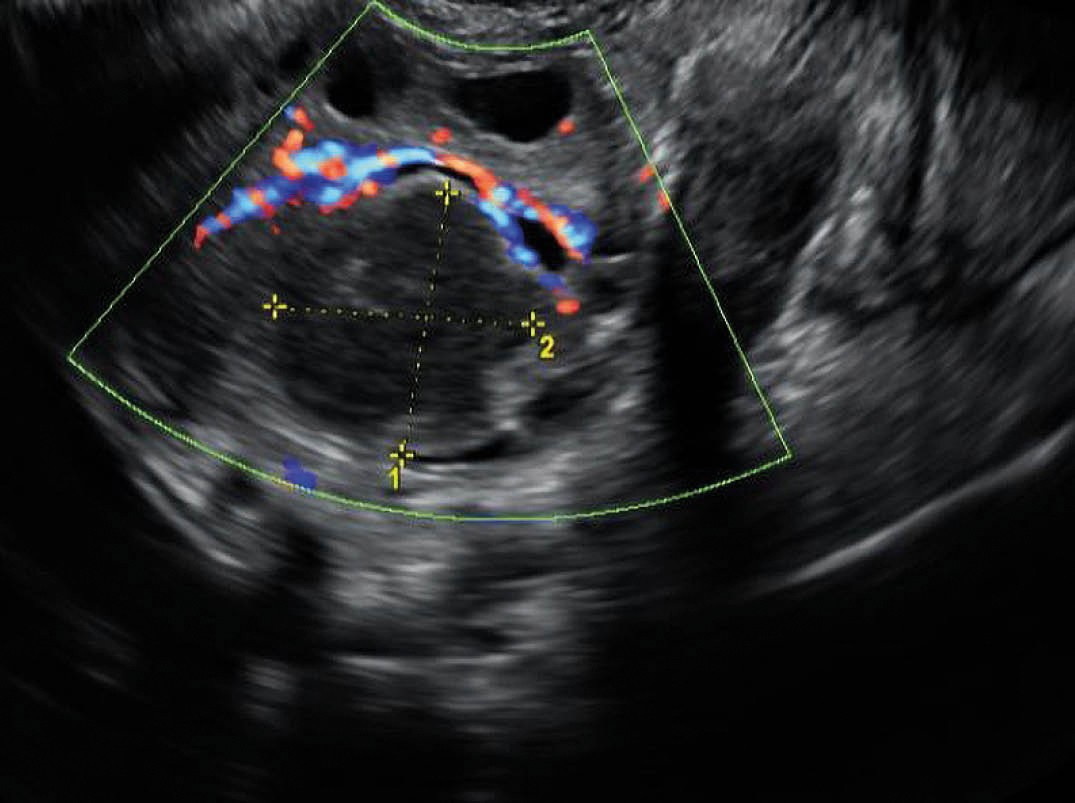

During the gynaecological examination, insertion of a vaginal speculum was clearly painful. The examination revealed abundant yellowish, viscous discharge with no particular odour. Transvaginal ultrasound showed bilateral hypoechoic ovarian masses (Figure 2). Ultrasound-guided transvaginal puncture was performed, yielding moderate amounts of pus. This was cultured for gonococci and mycobacteria in addition to standard aerobic and anaerobic flora. The specimen material was sent for testing on a flocked swab (eSwab). Cervical and vaginal secretions were tested for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae using PCR. In consultation with an infectious diseases specialist, the patient’s antibiotics were changed to ceftriaxone and metronidazole. This regimen is effective against abdominal abscesses as well as gonococci.

Figure 2 Vaginal ultrasound showed an ovarian cyst measuring 2.5 × 2.4 cm, with hypoechoic content.

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an acute or chronic infection of the upper genital tract, which can lead to endometritis, salpingitis, oophoritis, perihepatitis, peritonitis or a tubo-ovarian abscess. A tubo-ovarian abscess is usually the result of an ascending infection, caused by agents associated with sexually transmitted infections from the vaginal flora, or secondary infections from the gastrointestinal tract. Patients usually present with fever, reduced general condition and pain. The condition is potentially life-threatening and requires aggressive therapy. Gjelland et al. showed in 2005 that ultrasound-guided transvaginal aspiration in combination with antibiotics is safe for the treatment of tubo-ovarian abscesses, and proposed it as first-line therapy (7).

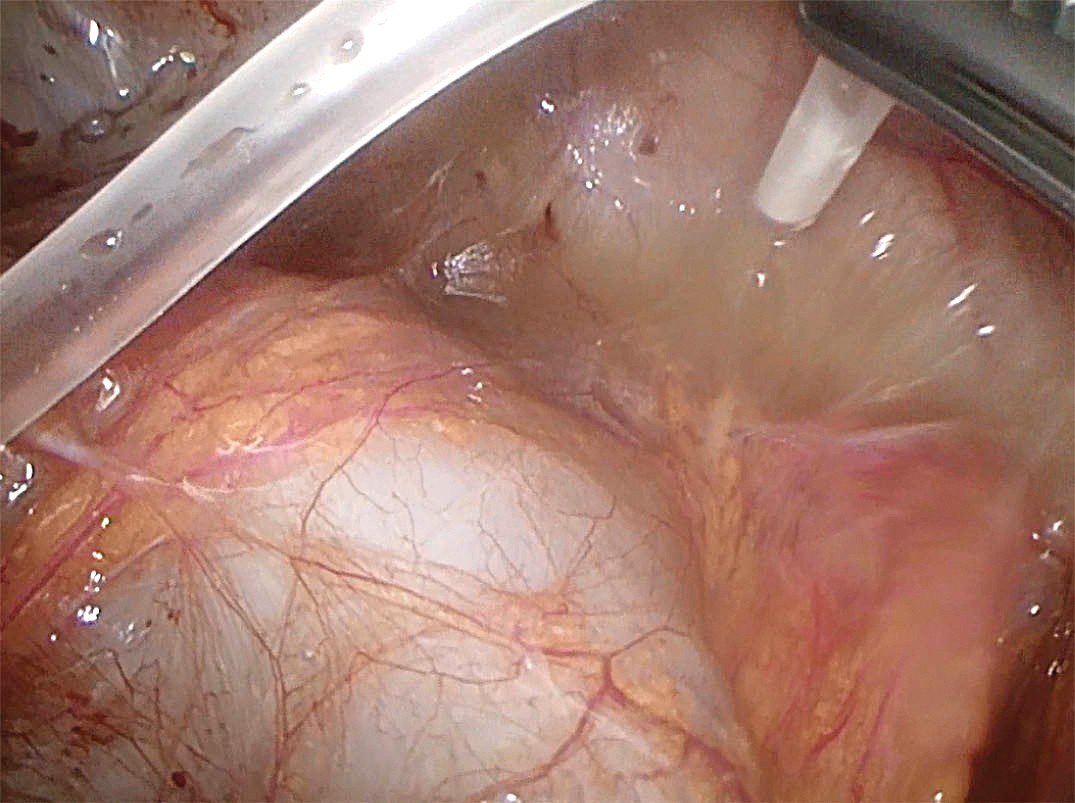

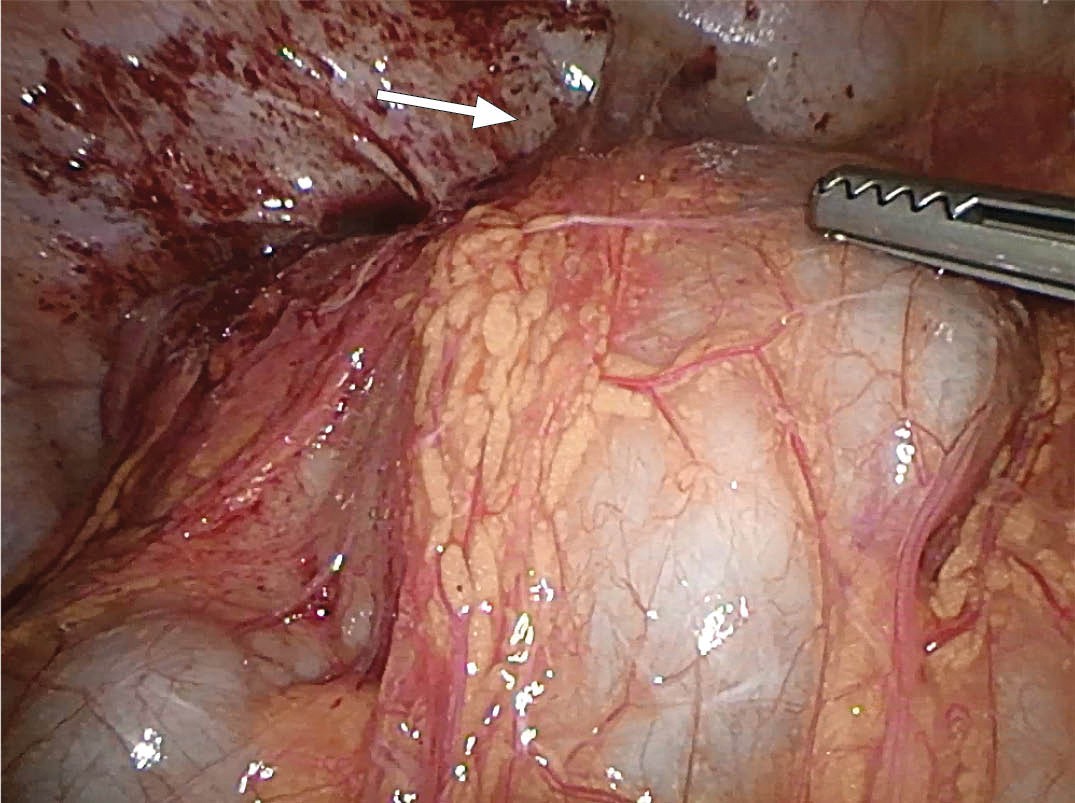

A clinical and biochemical response was initially seen after transvaginal aspiration, but the patient then experienced additional fever peaks of up to 39 °C, and showed increasing infection parameters after five days. Ovarian microbiological tests were negative. Six days after the aspiration, diagnostic laparoscopy revealed inflammation and widespread abdominal adhesions, as well as copious amounts of pus in the pelvis (Figures 3 and 4). Extensive adhesiolysis and irrigation were performed, and new microbiological specimens collected. On this occasion, a large quantity of pus was sent for testing on a sterile glass slide.

Figure 3 Image from laparoscopy. Free-flowing pus upon suction.

Figure 4 Image from laparoscopy. Lack of access to the lesser pelvis owing to adhesion between the intestines and the omentum. Arrow indicates the lesser pelvis.

In addition to aerobic and anaerobic cultures, real-time PCR of the 16S rRNA gene was performed on a sample of the pus and Ureaplasma urealyticum was detected.

Discussion

Our patient had been immunosuppressed with rituximab for 18 months; her increased vulnerability to upper respiratory tract infections most likely being a complication to the immunosuppression. The remainder of the medical history is consistent with a low-grade infection with an opportunistic microbe, Ureaplasma urealyticum, which gradually developed into a disseminated infection.

The genus Ureaplasma belongs to the Mycoplasmataceae family, and can cause various types of infections including genital tract infections. The microbe is considered part of the normal genital flora of sexually active men and women, but is potentially pathogenic (8). Disseminated infections can occur in immunocompromised individuals. U. urealyticum has not been shown to cause respiratory tract infections in adults, but can cause lung disease in neonates (9).

Systemic infection with U. urealyticum has been described in a previous case report in a 27-year-old woman undergoing rituximab treatment for multiple sclerosis (10). The patient presented with a high fever and abdominal pain, and a CT scan revealed bilateral renal abscesses. She responded to oral doxycycline treatment over six weeks. The report describes 23 other cases of invasive infection with different Ureaplasma spp. with varying organ manifestations. Common to almost all patients is that they were on immunosuppression therapy or undergoing treatment for cancer.

Our patient received two weeks of treatment with doxycycline, which resulted in complete response. She was discharged after two weeks in the gynaecological department, and was then followed with weekly blood tests, which showed normalisation of leukocyte counts and CRP levels after one week. A gynaecological examination two weeks after discharge showed normal findings. The patient had no symptoms and felt well. She was informed about an increased risk of infertility, especially fallopian tubal blockage as a result of the pelvic infection, and about the option of assisted reproduction in case of involuntary infertility. Chronic abdominal pain might be another complication of serious pelvic infection. During a consultation with the neurologist, it was decided to discontinue treatment with rituximab. The Norwegian Medicines Agency was notified of a possible causal link between the use of rituximab and the patient’s infections.

If antibiotic treatment proves ineffective in a patient with prolonged infection, then PCR must be considered to search for bacterial DNA (11). A common target is the 16S rRNA gene, which encodes part of the 30S ribosome. This gene is present in all bacteria, thus this method might reveal any bacteria present in the sample (both dead bacteria and bacteria that do not grow on standard culture media, such as U. urealyticum). In the case of our patient, a flocked swab dipped in pus was initially sent for analysis. However, this transport medium is unsuitable for general bacterial PCR. We do not routinely test for U. urealyticum, but in immunocompromised patients it is important to consider rare agents. The broadest possible microbiological diagnostic testing is achieved by supplying pus on a sterile glass slide with no additives, as well as a brush specimen in standard transport medium.

Conclusion

Severe infections in immunocompromised patients might pose diagnostic challenges. Our case report shows the importance of draining pus in purulent infections; not merely for therapeutic but also for diagnostic purposes. In addition, the report illustrates the need to obtain abundant sample material for microbiological genetic analysis, as well as the importance of effective collaboration across different medical specialties.