The percentage of pregnant women with an immigrant background is increasing in Norway, and in 2019, 28 % of all new-borns had a mother with an immigrant background (1). The risk of an adverse pregnancy outcome is higher among immigrant women than among the host population (2). A report from the Norwegian Directorate of Health in 2020 describes immigrant women as an especially vulnerable group within prenatal care (3).

An immigrant is defined as a person born outside of Norway with two foreign-born parents and four foreign-born grandparents (4). The term ‘country background’ refers to a woman’s country of birth or her parents’/grandparents’ country of birth if the woman was born in Norway (4). In the presentation of the articles, these terms will vary according to the definitions used in the study concerned.

The purpose of this literature review was to identify peer-reviewed articles that studied the prenatal health of immigrant women in Norway. It is intended to provide an overview of the available knowledge and reveal knowledge gaps that are relevant for the planning of future studies.

Evidence base

We conducted searches in the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Maternity & Infant Care and SveMed+ (see Appendix 1)

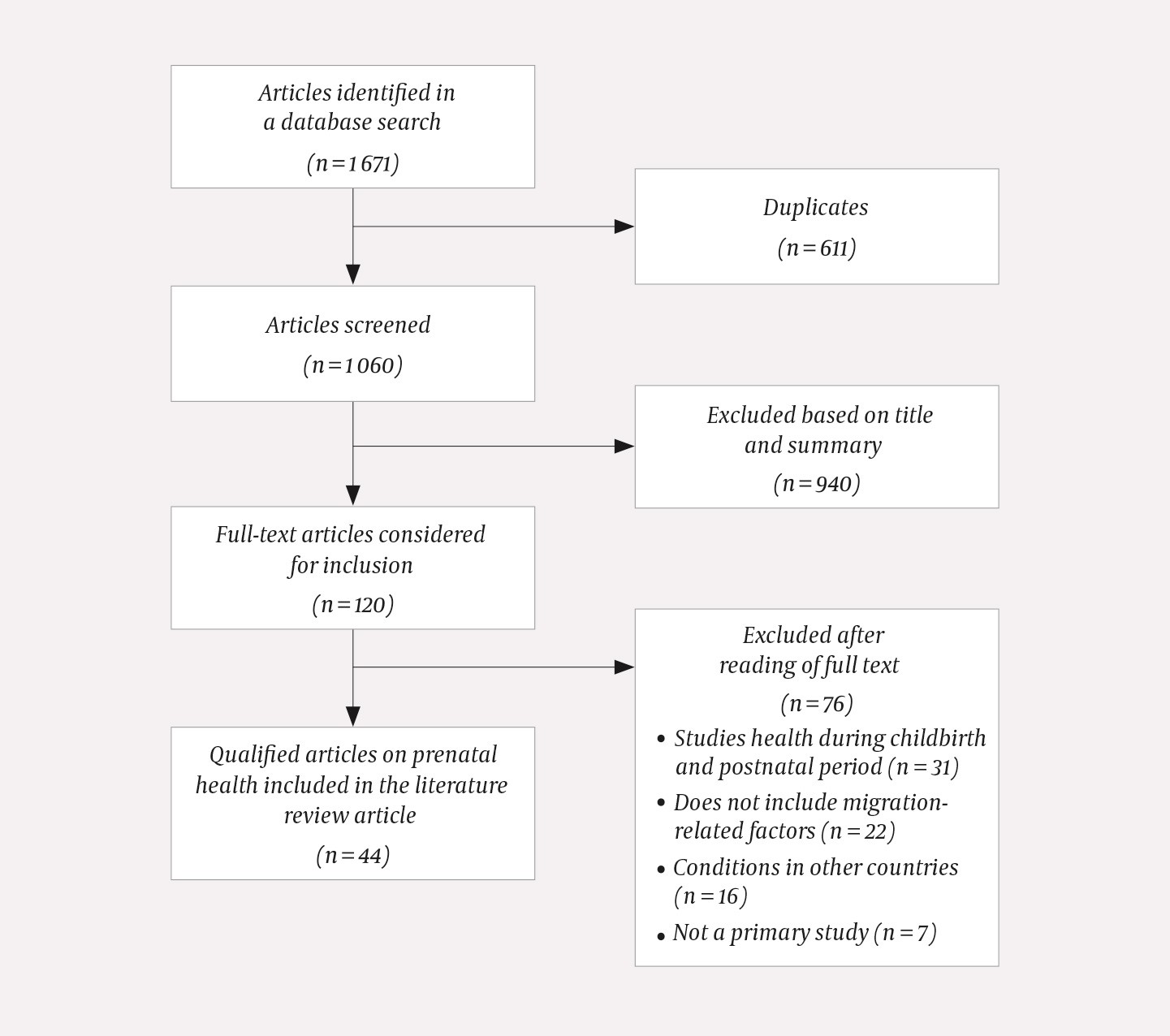

Inclusion criteria were as follows: original articles published in Norwegian or English in the period 2000–2019 that dealt with prenatal health and whose sample population was immigrants living in Norway. Using the Rayyan screening tool, the authors of this literature review independently assessed the relevance of the articles on the basis of the title and summary. All the authors read full-text versions of 120 articles and then selected 44 articles for inclusion in the literature review (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Flow chart of literature search.

Results

The 44 articles (5–48) were divided into eight categories by topic (see Appendix 2). A total of 42 articles were published in English and two in Norwegian (6, 36). Eight studies were qualitative, and the remainder were quantitative. The number of publications increased through the years, and 33 of 44 articles were published after 2010. Twenty articles were based on the same main study (STORK Groruddalen). Eleven studies were national in scope, while 29 studies included only women from Oslo. Thirty-one of the articles included immigrants and Norwegian-born women with immigrant parents, while the remaining 13 included only immigrants. One article included women with a foreign given name, and another included women whose native language was not Norwegian. The remaining studies were based on the women’s country of birth or their parents’ country of birth.

Gestational diabetes

Seven articles studied gestational diabetes. The risk of diabetes prior to pregnancy was more than twice as high for immigrant women as for Norwegian-born women (5). The prevalence of gestational diabetes was higher for women born in Asia and Africa than for Norwegian-born women (6, 7). Gestational diabetes accounted for 80 % of the diabetes cases among women born in Asia or Africa and 48 % of the cases among women born in Norway (5). Women from South Asia had insulin resistance and lower beta cell function more often than women from Western Europe (7, 8). Gestational diabetes in women from South Asia was associated with lower fetal weight than in women without gestational diabetes (9). No association was found between gestational diabetes and Vitamin D deficiency (10). Non-native speakers of Norwegian had less knowledge about gestational diabetes than native speakers (odds ratio (OR) 4.5) (11).

Weight, diet and physical activity

Seven articles studied weight, diet and physical activity during pregnancy. Women from Africa and Asia reported that the dietary advice they received was general and incongruent with their own food culture (12). Women from non-European countries had a higher risk of having unhealthy eating habits than European women, and the risk was highest for women from the Middle East and Africa (OR 21.5). These differences disappeared after adjustment for socioeconomic factors and level of integration (13). Women born in South Asia were less physically active (14, 15), had more subcutaneous fat (16) and abdominal obesity (17) than women from Western Europe. In the third trimester, weight gain was 2.7 kg and 1.3 kg higher, respectively, for women from Eastern Europe and the Middle East than for women from Western Europe (18).

Hyperemesis gravidarum

Five articles studied hyperemesis gravidarum. Multiple studies showed an increased risk of hyperemesis gravidarum among women with an immigrant background (19–21), especially among women born in South Asia (OR 3.3), sub-Saharan Africa (OR 3.4) and women with a foreign given name (OR 3.4) compared with Norwegian-born women and women with a Norwegian given name. The risk of hyperemesis gravidarum was not associated with length of residence in Norway (22), parental consanguinity (20) or Helicobacter pylori infection (23).

Preeclampsia and gestational hypertension

Four articles studied preeclampsia and hypertensive disorders. Immigrant women had a lower risk of preeclampsia than Norwegian-born women (OR 0.8), but the risk increased with increasing length of residence (24–26). The risk varied with the reason for immigration, and refugees had the highest risk (OR 0.8) compared with Norwegian-born women (26). In early pregnancy, women from non-European countries had lower blood pressure than women from Western Europe (27). Women born in South America, the Middle East, Africa and Asia had a lower risk of gestational hypertension (OR 0.5–0.6) than Norwegian-born women (25).

Vitamins, minerals and dietary supplements

Five articles studied vitamins, minerals and dietary supplements. Immigrant women and Norwegian-born women with immigrant parents used folate supplements less frequently than Norwegian-born women (28, 29), but their use increased with the length of residence (30). Adjusting for level of education eliminated the association between use of folate supplements and ethnicity (29). Severe Vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy was found in 45 % of women from South Asia, 40 % from the Middle East and 26 % from sub-Saharan Africa compared with 1.3 % of women from Western Europe (31). Women from South Asia, the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa had a higher prevalence of anaemia (14 %, 11 % and 7.3 %, respectively) than women from Western Europe (1.8 %) (32).

Fetal weight

Three articles examined fetal weight. Differences in fetal weight, length, abdominal circumference and body fat were found depending on the mother’s country of origin (33). However, the clinical value of using a universal standard for fetal weight in a multi-ethnic society was called into question, as only 21 % of the presumably healthy pregnancies met the standard (34). No association was found between Vitamin D status and fetal weight (35).

Experiences with the health service

Six articles discussed the experiences of immigrant women and health professionals with prenatal care. The immigrant women had limited health literacy (36), they requested information about their pregnancy (37), and they balanced their desire to be integrated into their new society with maintaining the traditions of their home country (38).

Health professionals felt that the health services did not adequately address the cultural diversity in Norway (39). Women who had previously experienced intimate partner violence wanted to bring up the topic and said that their fear of the child welfare services, language difficulties and their partner’s presence during the consultation were barriers to open communication (40). Health professionals found it difficult to talk about genital mutilation and said they lacked knowledge about the topic (41). Somali women who had undergone FGM felt that the prenatal care they received was suboptimal, and health professionals confirmed this (42).

Other

Six articles explored topics other than the aforementioned. Indian and Pakistani women gave birth to more boys than girls (43), but a study that included recent years found that this trend appears to have reversed (44). There was a decline in consanguinity among Pakistani parents (45). Immigrant women took sick leave more frequently than Norwegian-born women. This was partly attributable to poorer health prior to pregnancy, hyperemesis gravidarum and poor Norwegian language skills (46). The risk of gestational depression was higher for women from the Middle East (OR 2.4) and South Asia (OR 2.3) than for women from Western Europe (47). The prevalence of urinary incontinence during pregnancy was lowest for women from Africa (26 %) and highest for women from Europe and North America (45 %) (48).

Discussion

Gestational diabetes, hyperemesis gravidarum, preeclampsia, obesity and folate use are frequently studied topics. Some studies showed a lower prevalence of some pregnancy outcomes, but a majority of the studies showed a relatively high risk of disease among immigrant women, including a high prevalence of gestational diabetes. The findings emphasise the need for closer monitoring of immigrant women during pregnancy. Study results have led to changes in professional practice, such as the introduction of screening for gestational diabetes for women of Asian or African ethnicity (49).

An exploratory literature review includes studies regardless of the research study design, and it does not involve a formal quality assessment of the articles selected for inclusion, which distinguishes it from a traditional systematic review article (50). Since the authors did not assess the quality of the articles included in this review, the level of confidence in the results described in those articles cannot be assessed.

Our increased knowledge about the prenatal health of immigrant women can probably be attributed to the fact that a number of studies, such as STORK Groruddalen, specifically include immigrants. In recent years, national registries have also increased the possibility of including variables specific to immigrants (51). In 2010, an international panel recommended the inclusion of a minimum set of variables when conducting research on maternal health among immigrants (52). In descending order, this includes country of birth, length of residence, reason for immigration, language comprehension and ethnicity. In our material, factors other than country of birth and ethnicity were seldom included. Future research should include more migration-related factors that may provide a nuanced and more accurate picture of various risk profiles.

Differences in health outcomes are explained in part by language barriers (11, 53), but we found few studies on the association between language skills, use of interpreters and adverse pregnancy outcomes. We found no quantitative studies that investigated immigrant women’s use of prenatal care services or models for prenatal care especially adapted for immigrant women. International literature underscores the need for more knowledge about particularly vulnerable immigrant women, such as new arrivals, refugees and undocumented immigrants (53). We recommend that future studies do more to include these groups. Intervention studies that explore various measures for improving prenatal care have been conducted in Denmark and other European countries (54, 55) and should also be tested in Norway. Furthermore, we recommend conducting more qualitative studies that shed light on the experiences of health professionals and immigrant families.