Anterior shoulder dislocation can occur in connection with a traumatic event or as a result of an anatomical predisposition. A traumatic dislocation can damage stabilising structures, which can predispose an individual to recurrent dislocations. People under the age of 30 and those who participate in contact sports are particularly susceptible, and can consequently incur further damage to the stabilising structures. Patients in these categories should be considered for surgical treatment at an early stage.

The shoulder joint is the body’s most mobile joint and is therefore particularly prone to instability. Anterior shoulder instability is most common (in approximately 95 % of cases), followed by posterior and multidirectional instability. Shoulder instability can manifest itself in several ways (Table 1) (1), and patients with recurrent instability can suffer significant morbidity and impaired shoulder function. A study by Liavaag et al. estimated the incidence of anterior shoulder dislocations in Oslo to be approximately 26/100 000 person-years (2). The rate is three times higher in men, and among those under the age of 20, the incidence is 98/100 000 person-years (3). A previous trauma, often in connection with a collision or falling on an outstretched arm, is the most common trigger. Instability without a triggering trauma can occur in patients with joint hypermobility or as a result of repetitive microtrauma (e.g. among tradespeople and athletes) (4).

Table 1

Manifestations of anterior shoulder instability (1).

|

Manifestation

|

Explanation

|

|

Dislocation

|

Separation of the glenoid and the humeral head. Assisted reduction is typically required.

|

|

Subluxation

|

The humeral head slides over the glenoid rim but is reduced spontaneously. No need for assisted reduction.

|

|

Apprehension

|

The patient has pain/discomfort during arm abduction and external rotation. The patient is afraid to continue the movement because it feels as if they will put their shoulder out of joint.

|

According to a recent meta-analysis, as many as seven out of ten people may experience multiple instability episodes after dislocating their shoulder (5). The risk of recurrent dislocations depends on several factors, including the mechanism of injury, the extent of damage to the bony and soft tissue structures, and patient-specific factors such as gender, age and activity level (6). The purpose of this clinical review is to present data on which patient groups benefit from surgery, based on a literature search and the authors’ experiences from clinical practice.

Assessment

Most first-time anterior shoulder dislocation patients are treated non-surgically. If close to normal function is not achieved within a couple of weeks, the patient can be referred for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to screen for damage to the stabilising structures and to diagnose any additional injuries. If the pain or sense of instability persists, the patient may be referred for orthopaedic evaluation.

Patients who dislocate their shoulder often experience a subsequent feeling of instability and activity-related pain (7). The anamnesis should include questions about the mechanism of injury, joint hypermobility, previous instability episodes and treatment, activity level and expectations. Repeated episodes of instability increase the risk of recurrent dislocations and permanent damage to the shoulder joint (8–10).

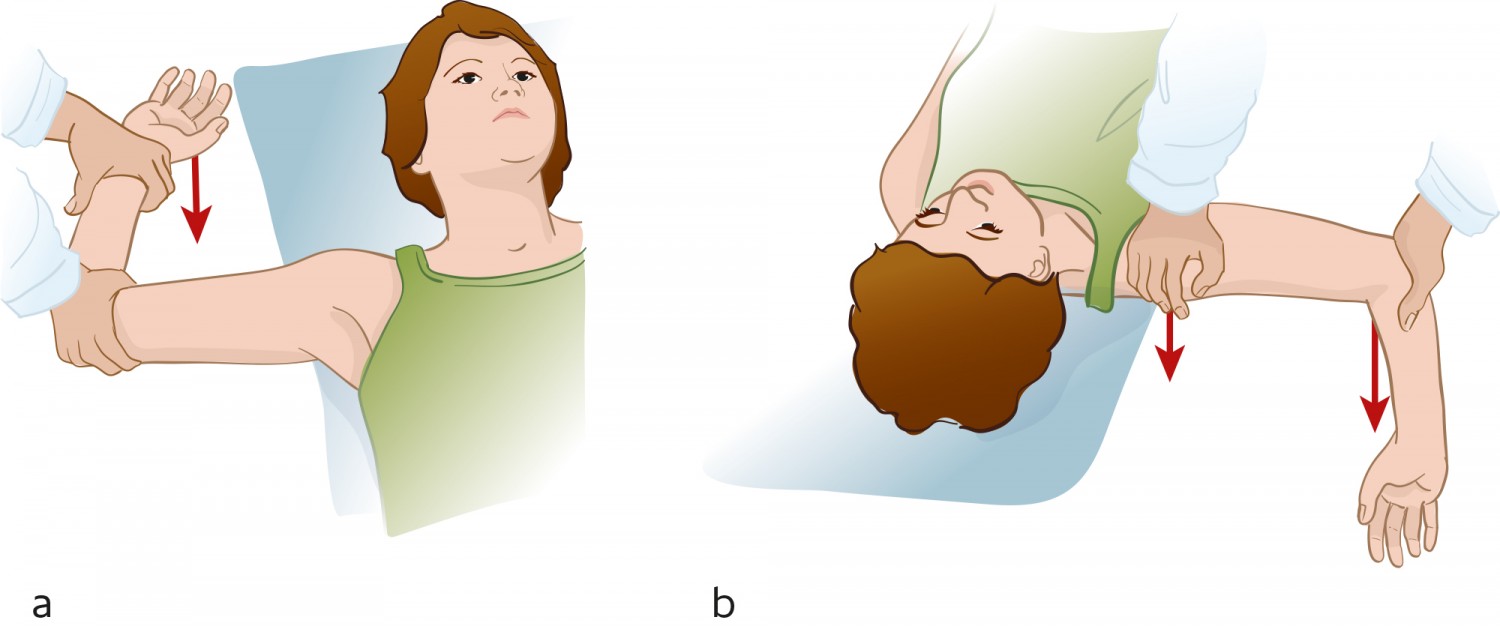

During a clinical examination, active and passive range of motion as well as strength in both shoulders need to be investigated. Apprehension and relocation tests, in which the arm is abducted and rotated outward, are sensitive and specific to anterior shoulder instability (Figure 1) (11). X-rays of the shoulder should be taken in cases of acute shoulder dislocation both before and after reduction. Anteroposterior images can reveal displaced bone fragments at the anterior edge of the glenoid and any other fractures. Lateral images (Y projection) are useful for confirming the direction of dislocation and the result after reduction.

Figure 1 a) The apprehension test entails abducting the patient’s shoulder to 90° and then applying outward rotational force. The test is positive if it triggers pain or a feeling of instability. b) The relocation test is positive if pressure on the humeral head removes the pain. Illustration: Illumedic

MRI scans are widely used to assess shoulder pathology and have a high sensitivity to injury to the rotator cuff and other non-osseous stabilising structures in the shoulder joint (12). The joint capsule and labrum will almost always be damaged in cases of first-time shoulder dislocation (13). The labrum plays a key role in glenohumeral stability and has to remain intact in order to maintain the negative intraarticular pressure (the vacuum effect) that keeps the humeral head in contact with the glenoid labrum.

A damaged labrum reduces the height of the glenoid rim by 80 % (14). Other structures that are often injured during anterior shoulder dislocation are the rotator cuff, the glenohumeral ligaments, the long head of the biceps tendon and its attachment to the glenoid labrum, and articular cartilage (13). MRI arthrography is often considered more beneficial in cases of chronic instability because it more accurately detects labrum tears (15).

Approximately one-third of patients with anterior shoulder dislocation experience a fracture of the anterior glenoid rim (9). A bony injury in connection with anterior shoulder dislocation increases the risk of recurrent instability episodes and a reduced function level (10). The glenoid fragment is usually resorbed, and this reduces the joint surface (16). Glenoid bone loss of 15–20 % is considered to be a critical limit, because it increases the risk of repeated instability episodes and impaired shoulder function (16).

Impression fractures of the humeral head (Hill-Sachs lesions) can be observed in up to 93 % of first-time cases of shoulder dislocation (4). Historically, these lesions have not been regarded as significant, but in a recently published article, Yamamoto et al. demonstrated that the size and location of the Hill-Sachs lesions impacted on the function level, pain and the risk of recurrent dislocations (17). The extent of the bone loss on the glenoid must be seen in conjunction with the size and location of the Hill-Sachs lesion. Computed tomography (CT) with three-dimensional imaging is an important aid for identifying and evaluating bone damage in the shoulder, particularly in patients with recurrent dislocations (18).

Treatment

The treatment strategy for anterior shoulder instability is based on the anamnesis, clinical examination and radiological findings. The patient’s age, gender, activity level and expectations are all key factors. Young age at the first episode of dislocation is one of the main prognostic factors for recurrent instability (19).

Acute shoulder dislocation

Acute shoulder dislocation is extremely painful, and reduction should be performed as soon as possible. One to two per cent of patients with acute anterior shoulder dislocation suffer neural and vascular injury (20). For patients who do not live near medical treatment facilities, reduction can be attempted before X-rays are taken. Oslo University Hospital’s Orthopaedic Emergency Section recommends intra-articular anaesthesia with lidocaine, combined with intravenous pethidine or diazepam where necessary.

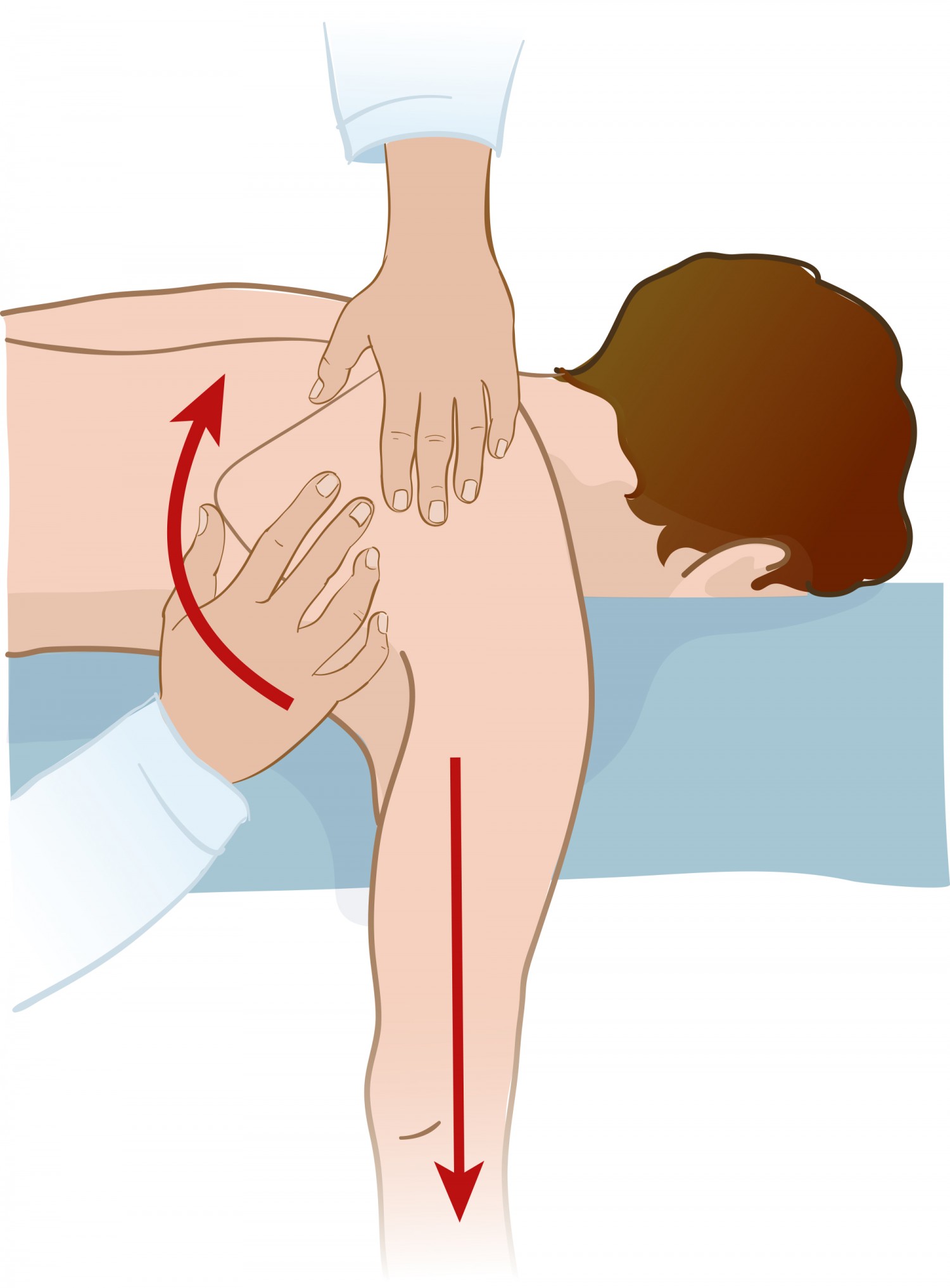

Closed reduction of a shoulder dislocation must be carried out gently to avoid further injury. Our recommended method is the hanging arm method (Figure 2). Closed reduction is successful in most acute shoulder dislocations. However, reduction becomes more difficult the longer the shoulder is dislocated. Reduction is also more complicated if the humeral head is dislocated posteriorly, soft tissues are interposed, the humeral head is trapped under the conjoint tendon or the glenoid is fractured. If the joint cannot be reduced gently, we recommend that the patient be sent to hospital as quickly as possible for reduction under general anaesthesia or nerve block, or open surgical reduction if necessary (21). If the joint can be reduced gently, referral for further clinical follow-up and diagnostic imaging by the specialist health service should be considered after approximately two weeks.

Figure 2 Hanging arm for closed reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation. The patient needs to lie prone on their stomach with their arm hanging down. Pull the arm gently or use weights. Push the lower corner of the shoulder blade towards the midline and rotate the hanging arm whilst applying traction. Illustration: Illumedic

The patient can use a sling for a few days to relieve the pain, but should start active rehabilitation as soon as possible (22). There is no evidence that using a sling reduces the risk of future dislocations (22).

Surgery

Young people (<30 years) and active patients should be considered for surgery as the risk of recurrent dislocations is high. Surgical stabilisation at an early stage can prevent further damage to shoulder stabilising structures (23). Traditionally, first-time anterior shoulder dislocation patients have undergone non-surgical treatment. However, a recently published meta-analysis showed that seven out of ten such patients experience recurrent episodes of instability following non-surgical treatment (5). Half will subsequently need surgical stabilisation (5).

A wait-and-see approach and repeated episodes of instability can cause further injury to the stabilising structures, including increased bone loss. The loss of function in cases of repeated episodes of instability is not well documented, but the aforementioned meta-analysis consisting of randomised controlled and prospective cohort studies indicated that young patients and individuals who rely heavily on their shoulders to perform can benefit from surgical stabilisation after first-time shoulder dislocation, particularly where bone loss has been established and a high function level is needed, such as in contact sports (5, 24).

The risk of non-recurrence-related complications following arthroscopy after first-time shoulder dislocation is 1.6 %. This includes subcutaneous suture abscesses, transient paraesthesia, and frozen shoulder (5).

Soft tissue procedures

Injury to the anterior labrum is known as a Bankart lesion, named after Arthur Bankart, a British surgeon. The Bankart procedure, where the labrum and associated joint capsule are repaired, is the most common surgical procedure for anterior shoulder instability, and nowadays tends to be performed arthroscopically. The risk of recurrent instability after surgery is higher in cases of glenoid bone loss (25). If the glenoid bone loss is moderate (15–20 %), but there is still a large Hill-Sachs lesion on the humerus, additional procedures are recommended. One such procedure is remplissage (French for ‘to fill in’), which entails attaching the infraspinatus tendon to the Hill-Sachs defect on the humerus. The additional procedures increase stability, but can lead to reduced joint mobility (26). The reported recurrence rate after Bankart surgery is approximately 10 % (5).

Bone block procedures

In cases of significant glenoid bone loss (> 20 %), it may be beneficial to transplant bone to the anteroinferior edge of the glenoid. The coracoid process and iliac crest bone are most commonly used. Transferring the coracoid process from the same side to the anterior edge (the Latarjet procedure) is the most common bone block procedure. The bone block increases stability by replacing bone loss and also strengthens the anterior capsule via a sling effect at the conjoint tendon attached to the coracoid process. The procedure has traditionally been performed as open surgery, but can also be done arthroscopically.

Postoperative rehabilitation

After shoulder stabilising surgery, a sling and restricted movement are recommended for 3 - 4 weeks, but patients are encouraged to start passive exercises as soon as the pain allows (27). After 4 - 6 weeks, full range of motion is allowed, and patients should gradually start strength training. Rehabilitation is tailored to the individual patient, and it is recommended that this is done under the guidance of a physiotherapist or manual therapist. Resumption of sports is not recommended for at least three months. For extreme and contact sports, it is recommended that the patient waits at least six months.