Examinations are a key component of medical studies and are used as a tool for learning and for assessing whether the students possess the requisite knowledge (1). Since the examinations function as a quality control for further progress in medical studies and for graduation with an authorisation to practise medicine, it is necessary to define a limit for what is deemed satisfactory, or limits for different grades. This is called setting the standard of the examinations.

The examination standard can be defined by using relative or absolute methods. Relative standards are based on a well-defined group and the pass grade is based on total performance in this group. The group’s average point score minus one standard deviation is an example of a relative limit for a pass grade. Absolute standards are based on a pre-defined limit and are independent of the group’s total performance. Absolute methods are suitable for testing whether the students possess satisfactory competence for a specific purpose, such as for study progression or work as a doctor. The two most common absolute standard-setting methods are those created by Angoff and Ebel. Both methods are based on an assessment of the degree of difficulty of each examination question by an expert panel, and the sum of these estimates is defined as the limit for a pass grade in the examination (2, 3). The pass-grade limit will hence vary from one test to another, based on their respective degree of difficulty. The use of expert panels is costly in terms of funding, time spent and organisational resources. The same pass-grade limit from one year to the next would constitute a simpler absolute standard-setting method, but this approach would not take the degree of difficulty of the test into account.

Practices at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) mainly include an annual, integrated examination, meaning that all subjects taught in the year in question are tested in the same examination. The limit for a pass grade is pre-defined as at least 65 % correct answers, hereafter referred to as ‘absolute 65 %’. The failure rate for an examination varies from one year to the next, without any indication of major differences between the student cohorts in the admission requirements (4). Since only a single examination is held each year, the stakes are high and the students need to perform well. Rescheduled examinations (re-sit examinations) are held in August. If a student fails this examination as well, he or she must retake the entire year of study. A failure will thus entail major social and financial consequences for the student, and financial and organisational consequences for the medical faculty. Since examinations represent both a quality control instrument and a learning tool, and because the consequences of a fail grade are considerable, strict requirements must be upheld when it comes to the quality of the examinations. To have proper credibility, the standard-setting method ought to take the degree of difficulty of the examination into account (5).

Both relative and absolute standard-setting methods have their weaknesses. Absolute methods that involve expert panels are resource-intensive and hard to implement. Relative methods may result in unacceptably low limits for a pass grade. If some students fail to prepare for the examination, this will lower the average performance and thus also the limit to a pass grade. Another problem inherent in many relative methods is that someone will invariably fail, and this may mean that even students with sufficient knowledge will fail if the group as a whole performs strongly. Focusing on these weaknesses, Cohen-Schotanus and van der Vleuten developed a new method in 2010 (5). They claim that the academically strongest students represent one stable factor in the process of setting the standard. These students have read and understood the syllabus and prioritised their studies, but they will also be affected by the degree of difficulty of the examination. By using the academically strongest students as a reference group, they developed what today is known as Cohen’s method, hereafter referred to as ‘original Cohen’ (5). This method has later been revised by others (6).

We have compared the current 65 % absolute limit to a pass grade with two different Cohen methods (‘original Cohen’ and ‘modified Cohen’). We have investigated how these methods affect the failure rate and the standard deviation of this rate. Our hypothesis was that examinations with a high failure rate had a high degree of difficulty, while examinations with zero or very few failures were easier. We therefore assumed that a Cohen method that takes the degree of difficulty into account would result in fewer failures in difficult examinations and possibly more failures in simpler examinations, thus reducing the standard deviation of the failure rate as a whole.

Material and method

The data set

The data set for this study consists of examination results from the medical study programme at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). A written examination is held every other semester for the first four years, with no examination after the 9th and 10th semesters, but after both the 11th and 12th semesters. The examination consists of two parts; one part with 100–120 multiple-choice questions that have 3–5 response alternatives and a free-text/essay component with 3–5 main topics. The multiple-choice component counts for 60 %, while the free-text/essay component counts for 40 % (7). All ordinary written examinations for the years 2010 through 2015 were assessed, and all were included, except for the examination in the 11th semester of 2010 due to missing data. Table 1 lists the subjects that are tested in the different examinations. On average, there were 111 candidates in each examination and 34 examination sets were included, totalling 3 779 examination papers.

Table 1

Overview of the subjects that are tested on in each examination

|

Study year

|

Semester

|

Basic/paraclinical subjects

|

Clinical subjects

|

|

1st study year

|

1st–2nd semester

|

Cell biology

Biochemistry

Genetics

Histology

Embryology

Medical terminology

Medical history

Medical ethics

The musculoskeletal system

Anatomy: muscles, skeleton

|

Doctor-patient course in general practice

|

|

2nd study year

|

3rd–4th semester

|

Structure and function of the nervous system

Anatomy: ear, eye, larynx, genitalia

Embryology

Medical statistics

Genetics

Medical ethics

Microbiology

Immunology

Endocrinology

Renal physiology

Occupational medicine

Toxicology/environmental medicine

Pharmacology

Pathology

|

Doctor-patient course

(completed in January)

|

|

3rd study year

|

5th–6th semester

|

Pathology

Microbiology

Pharmacology

Clinical chemistry

Epidemiology

Behavioural medicine

Diagnostic imaging

Immunology

|

Otorhinolaryngology

Ophthalmology

Neurology

Neurophysiology

Physical medicine

Oncology

Geriatrics

Infection medicine

Haematology

Cardiology

Pulmonary medicine

Thoracic surgery

Gastroenterology

Gastric surgery

|

|

|

7th–8th semester

|

Pathology

Diagnostic imaging

Tropical medicine

Community medicine

Microbiology

Pharmacology

|

Emergency medicine

Dermatology

Orthopaedics

Rheumatology

Infection medicine

Psychiatry

Obstetrics

Gynaecology

Paediatrics

Endocrinology

Nephrology

Urology

Plastic surgery

|

|

6th study year

|

11th semester

|

General practice medicine

Occupational medicine

Geriatrics

Environmental medicine

Community medicine

Epidemiology

Medical statistics

Clinical decision-making theory

Health service administration

Health service economics

Women’s health

Medical ethics

Forensic medicine

|

|

|

6th study year

|

12th semester

|

Summary semester

|

|

Estimation of the original and modified Cohen

Estimation of the ‘original Cohen’ starts from the point score of the students in the 95th percentile and defines the limit for a pass grade as 60 % of this score. In addition, it corrects for the possibility that the students may have guessed the correct answer. The formula for the ‘original Cohen’ is (5): Limit for a pass grade = cN + 60 (N*- cN), where c is an estimate of the proportion of correct answers that are attributable to guesswork, N is the maximum score and N* is the score of the 95th percentile. We have corrected for guesswork using the same method that Cohen-Schotanus used in his study (Cohen-Schotanus, personal communication, 2016). The proportion of correct answers that are attributable to guesswork (cN) is estimated as follows: cN = (0.33 × A) + (0.25 × B) + (0.20 × C), where A, B and C are the proportions of answers that have three, four and five response alternatives respectively. ‘Original Cohen’ was created with a view to examinations that have only multiple-choice questions. Since the examinations at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) include a multiple-choice as well as a free-text/essay component, we correct for guesswork only in the multiple-choice component, while using the 95th percentile of the total point score for the entire set of questions (multiple-choice + free-text/essay component).

The ‘modified Cohen’ is estimated using the following formula (6): limit for a pass grade = K × Px, where K is the factor with which we multiply the score Px of the students in the given percentile. We entered different values for K (0.65, 0.70 and 0.75) and obtained the associated limits for a pass grade and failure rates. The choice of K values in our study is based on the existing 65 % limit for a pass grade and therefore investigates the failure rates around this limit. Taylor found that the point score of the students in the 90th percentile represented a better reference point than the 95th percentile that was used in the ‘original Cohen’ (6). The ‘modified Cohen’ method does not correct for guesswork.

Analyses

The following statistical analyses and estimates were made in Google Sheets 2016: average, median, failure rate, standard deviation (SD) of the failure rate, 90th and 95th percentiles and correction for guesswork.

Ethics

The examination results are available as anonymised data, and no individuals can be identified. An application for permission to undertake this study was thus not deemed necessary.

Results

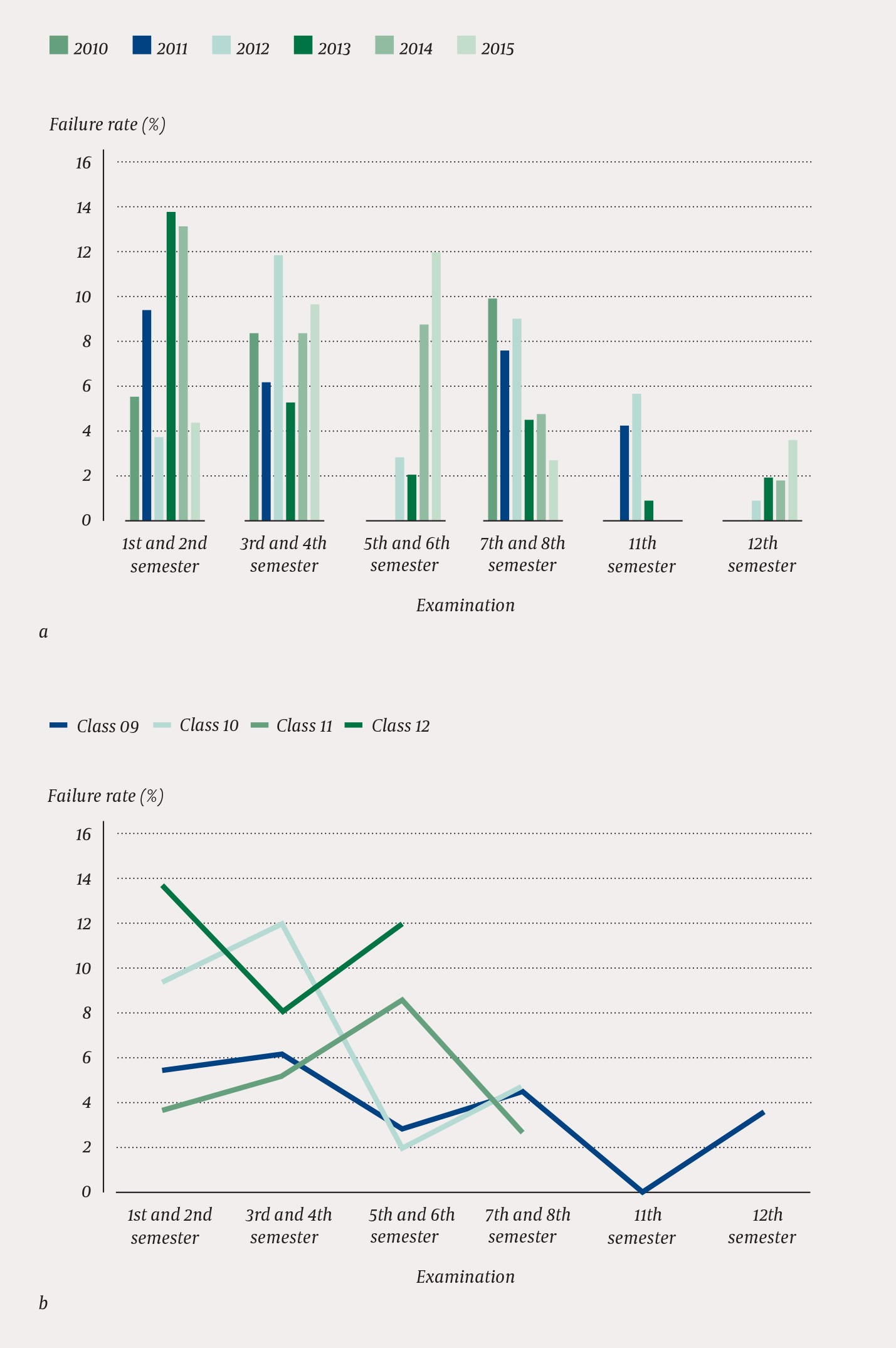

The current 65 % method resulted in variations of up to 12 % in the failure rate for the same examination in the course of study during the period investigated (Figure 1, Table 2). For example, in the examination in the 5th–6th semester in 2010–11, there were no failures, whereas in 2015, altogether 11 students (12 %) failed (Figure 1a). The failure rate declined during the course of study (Figure 1b) and remained the same for all standard-setting methods.

Figure 1 a) Proportion of medical students who have failed the annual examinations at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) 2010–15 with the current standard-setting method of 65 % correct answers needed for a pass grade. b) Failure rate (%) of four classes monitored over time; class 09 started in 2009, class 10 in 2010 etc. The x axis shows the examinations from which the data have been retrieved, while the y axis shows the failure rate in per cent.

Table 2

Overview of examination data for each examination included in the study

|

Semester

|

Examination

|

Number of candidates

|

Average score

|

Median score

|

Number of failures (%)

|

|

1st and 2nd

|

2010

|

110

|

78,7

|

80

|

6 (5.45)

|

|

1st and 2nd

|

2011

|

117

|

76,9

|

79

|

11 (9.40)

|

|

1st and 2nd

|

2012

|

108

|

77,9

|

78

|

4 (3.70)

|

|

1st and 2nd

|

2013

|

117

|

78,6

|

76

|

16 (13.68)

|

|

1st and 2nd

|

2014

|

115

|

74,2

|

77

|

15 (13.04)

|

|

1st and 2nd

|

2015

|

114

|

76,3

|

77

|

5 (4.39)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3rd and 4th

|

2010

|

121

|

74,4

|

74

|

10 (8.26)

|

|

3rd and 4th

|

2011

|

113

|

77,4

|

78

|

7 (6.19)

|

|

3rd and 4th

|

2012

|

118

|

73,7

|

77

|

14 (11.86)

|

|

3rd and 4th

|

2013

|

114

|

77,4

|

78

|

6 (5.26)

|

|

3rd and 4th

|

2014

|

109

|

75,1

|

77

|

9 (8.26)

|

|

3rd and 4th

|

2015

|

114

|

76,1

|

77

|

11 (9.65)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5th and 6th

|

2010

|

103

|

80,1

|

81

|

0 (0.00)

|

|

5th and 6th

|

2011

|

110

|

83,3

|

84

|

0 (0.00)

|

|

5th and 6th

|

2012

|

107

|

77,4

|

78

|

3 (2.80)

|

|

5th and 6th

|

2013

|

99

|

78,5

|

79

|

2 (2.02)

|

|

5th and 6th

|

2014

|

105

|

77,4

|

79

|

9 (8.75)

|

|

5th and 6th

|

2015

|

92

|

73,6

|

74

|

11 (11.96)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7th and 8th

|

2010

|

112

|

73,3

|

74

|

11 (9.82)

|

|

7th and 8th

|

2011

|

119

|

75,9

|

77

|

9 (7.56)

|

|

7th and 8th

|

2012

|

111

|

79,1

|

81

|

10 (9.01)

|

|

7th and 8th

|

2013

|

112

|

77,4

|

78

|

5 (4.46)

|

|

7th and 8th

|

2014

|

105

|

77,7

|

80

|

5 (4.76)

|

|

7th and 8th

|

2015

|

111

|

77

|

77

|

3 (2.70)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11th

|

2011

|

118

|

82

|

77

|

5 (4.24)

|

|

11th

|

2012

|

107

|

75,1

|

76

|

6 (5.61)

|

|

11th

|

2013

|

113

|

83,2

|

85

|

1 (0.88)

|

|

11th

|

2014

|

108

|

80,9

|

81

|

0 (0.00)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12th

|

2010

|

109

|

82

|

82

|

0 (0.00)

|

|

12th

|

2011

|

118

|

80,2

|

81

|

0 (0.00)

|

|

12th

|

2012

|

118

|

80,6

|

81

|

1 (0.85)

|

|

12th

|

2013

|

106

|

78,6

|

79

|

2 (1.89)

|

|

12th

|

2014

|

115

|

78,9

|

80

|

2 (1.74)

|

|

12th

|

2015

|

111

|

79

|

79

|

4 (3.60)

|

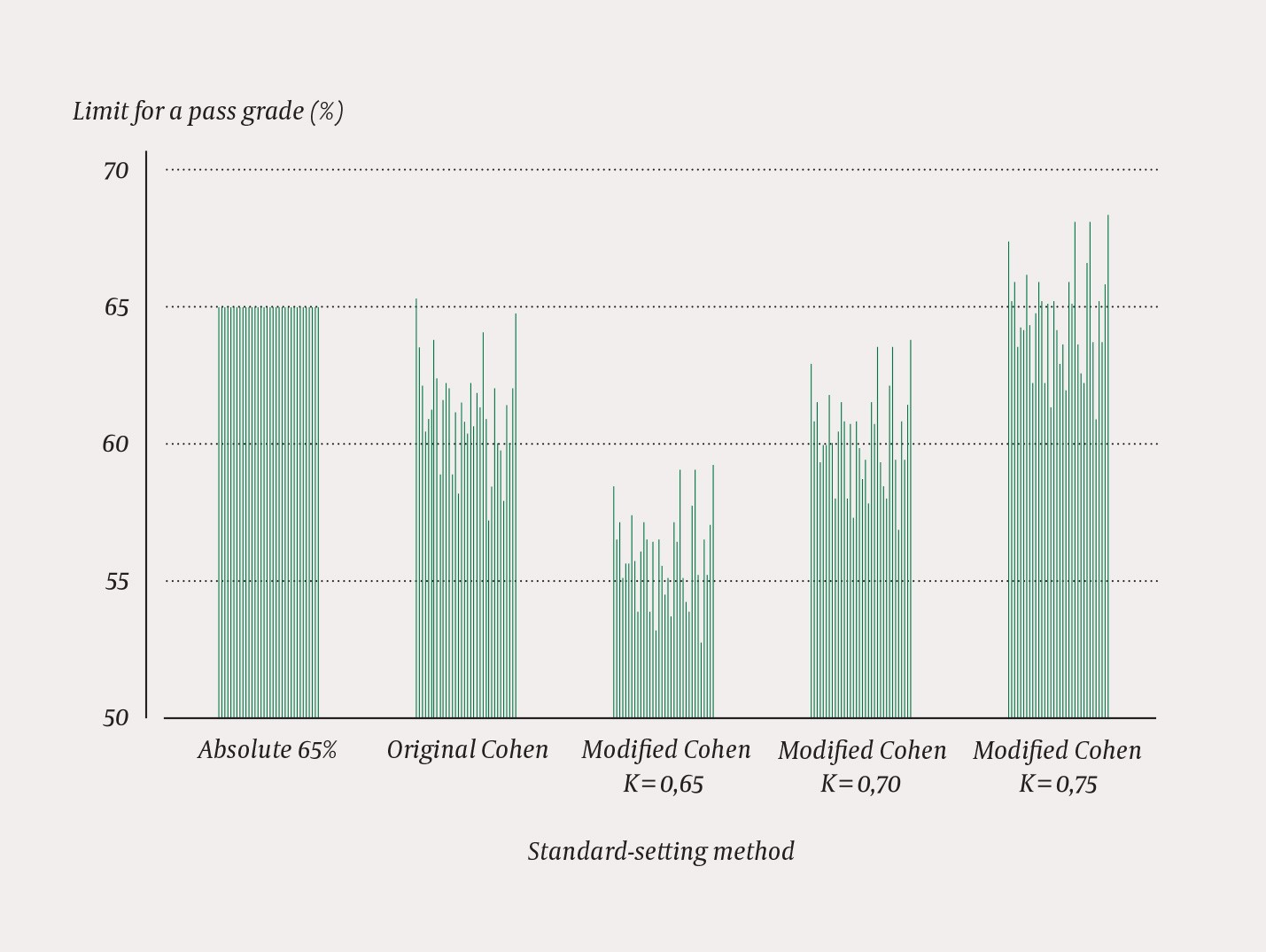

The limit for a pass grade with the ‘original’ and ‘modified Cohen’ methods with K values of 0.65 and 0.70 was lower than with the ‘absolute 65 %’ limit. Use of a ‘modified Cohen’ method with a K value of 0.75 caused the limit for a pass grade to waver around the limit in use today (Figure 2). Using the ‘original Cohen’ the limit for a pass grade amounted to 57–65 % and with the ‘modified Cohen’ to 53–68 %, depending on the K value applied (Table 3).

Figure 2 Comparison of the limits for a pass grade in all examinations of medical studies at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology 2010–15 with use of different standard-setting methods. Each column represents an examination. The Y axis shows the limit for a pass grade, the X axis shows the various methods.

Table 3

Comparison of the limit for a pass grade and the failure rate for the different standard-setting methods (absolute 65 %, original and modified Cohen methods) for all examinations irrespective of semester at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) 2010–2015

|

Method

|

Absolute 65 %

|

Original Cohen

|

Modified Cohen K = 0.75

|

Modified Cohen K = 0.70

|

Modified Cohen K = 0.65

|

|

Average limit for a pass grade (%)

|

65.0

|

62.3

|

64.7

|

60.6

|

56.0

|

|

Standard deviation, limit for a pass grade

|

0.0

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.4

|

1.3

|

|

Range, limit for a pass grade (%)

|

65.0

|

58.1–64.7

|

61.5–67.6

|

57.4–63.1

|

53.3–58.6

|

|

Average failure rate % (n)

|

5.2 (6)

|

3.9 (4)

|

5.0 (5)

|

3.0 (3)

|

1.7 (2)

|

|

Standard deviation, failure rate

|

4.2

|

3.7

|

4.4

|

3.1

|

2.1

|

|

Range, failure rate (%)

|

0–13.7

|

0–13.7

|

0–19.7

|

0–10.4

|

0–8.5

|

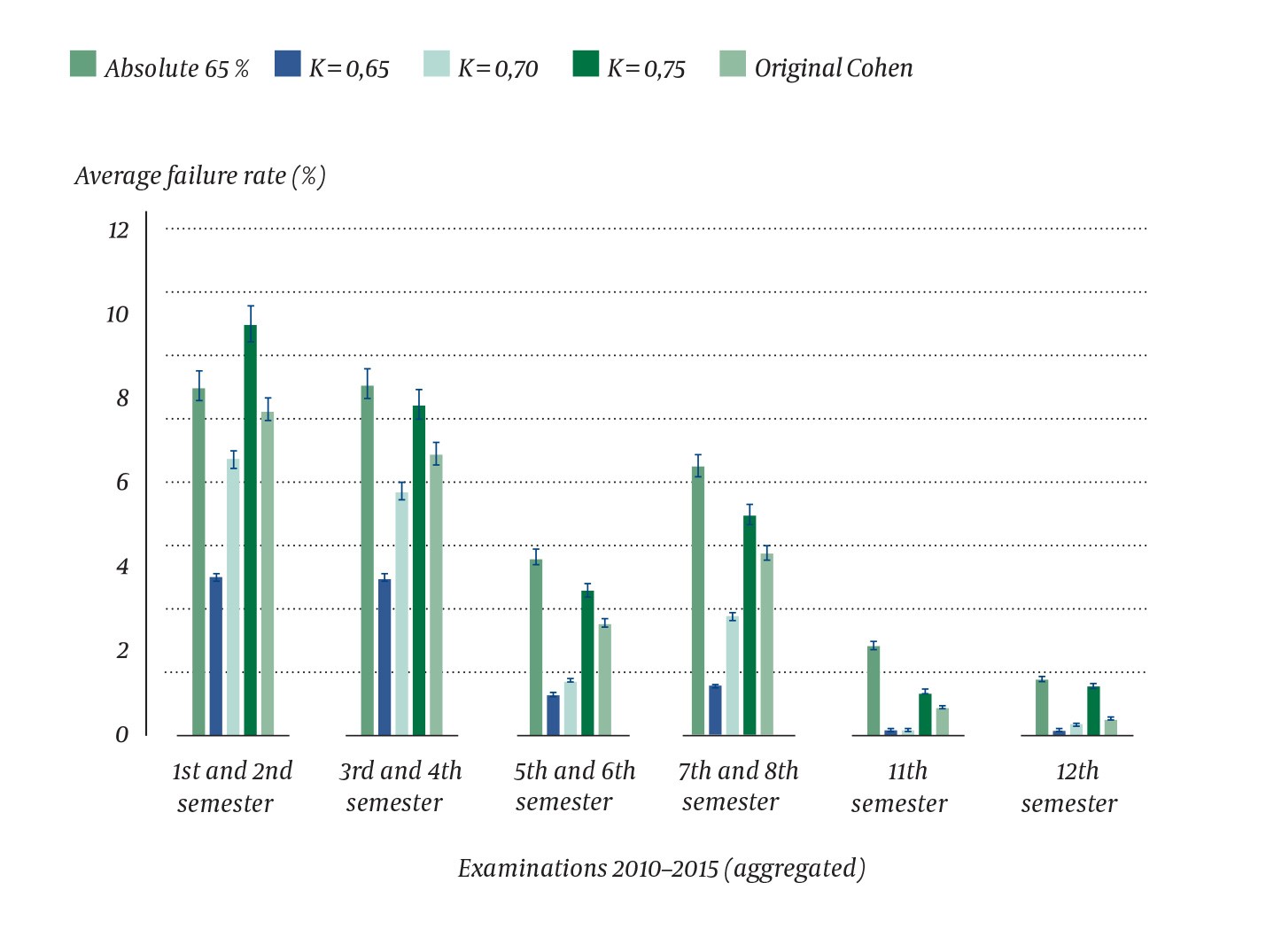

With the exception of the examination in the first year of study, the failure rate was lower with both the original and modified Cohen methods when compared to the current method (Figure 3, Table 3). ‘Original Cohen’ produced the same range in the failure rate as the ‘absolute 65 %’ (0–13.7 %), but reduced the average proportion of failures from 5.2 % to 3.9 %. ‘Modified Cohen’ with K values of 0.65 and 0.70 reduced the standard deviation (SD) and the total failure rate. ‘Modified Cohen’ with a K value of 0.70 has an average failure rate of 3.0 % (SD 3.1) and a range of 0–10.4 %, while the ‘absolute 65 %’ has an average failure rate of 5.2 % (SD 4.2) and a range of 0–13.7 %. ‘Modified Cohen’ with a K value of 0.75 produced a wider range in the failure rate than the ‘absolute 65 %’ method, and thus also a higher standard deviation (Table 3). The standard deviation of the failure rate decreased with a lower limit for a pass grade.

Figure 3 Average failure rate in per cent including the standard deviation for each examination with use of the different standard-setting methods at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) 2010–2015. The X axis shows the examinations in the course of study, while the Y axis shows the average failure rate

Discussion

We found that the proportion of medical students who fail their examinations varies from one year to the next in the same examination in the course of the medical studies. We have shown that the standard deviation of the failure rate can be reduced by using Cohen’s methods, but that this comes at the cost of a lower limit for a pass grade.

The study shows that the failure rate declines as the medical studies progress. We have not investigated the causes of this phenomenon, but they are likely to be multiple. The medical studies programme in Trondheim practises spiral learning, meaning that the same topic is studied approximately every other year. For example, cardiac physiology with clinical examples is taught during the first year and cardiology in the third year, with summary of cardiology in the final year. Through this spiral learning the students will deepen their understanding of the subject. Furthermore, from upper secondary school the students have become accustomed to a clearly defined syllabus and frequent testing. The medical studies programme at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), on the other hand, has learning objectives with a number of recommended textbooks and only 1–2 annual examinations which may test anything. The change in study technique will thus be a major challenge to many students, although most of them appear to learn how to cope with this during their studies. In addition, the attrition rate is highest during the first two years of study, when 2–6 students need to retake a year, while only a maximum of one student needs to retake any later years. Of those who quit or have their admission revoked because of repeated examination failures, altogether 73 % (101 of 137 based on figures from 1999–2016) had not completed the second year of study (personal communication, Mona Dalland Stormo and Marte Laugen, Student and Academic Section at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). Other factors that can be assumed to contribute include experience of examinations, increasing age and the subjects being perceived as more relevant at later stages of the studies, which may help boost motivation.

The study by Cohen-Schotanus compared two cohorts at two different medical faculties in the Netherlands (5). One faculty used a reference-based method, and the average score minus one standard deviation was used to define the limit for a pass grade. This limit hence varied between 15 % and 46 %, while the failure rate remained relatively stable at 17 %. The other faculty used a pre-defined 60 % limit for a pass grade, and the failure rate amounted to 17–97 % (53 % on average). It is conceivable that the students who were subject to a higher limit for a pass grade were more knowledgeable. However, the students in these cohorts performed equally well in the national progress test which is implemented in six of the eight medical faculties in the Netherlands (5). However, students at the faculty with a 60 % pre-defined limit for a pass grade and a high failure rate spent on average one more year to complete their studies. Considering that these cohorts were equally knowledgeable in the national test, this indicates that pre-defined, absolute limits for a pass grade are a waste of public resources, and not least the students’ time and resources (5).

Both the original and modified Cohen methods reduced the standard deviation of the failure rate. With the use of these methods, fewer students would have failed. We were surprised to see that the opposite never occurred, i.e. that more students failed in examinations that nobody with an absolute limit for a pass grade failed. We believe that the Cohen method that ought to be chosen is the one that produces the largest reduction in the standard deviation of the failure rate, but the smallest change in the limit for a pass grade. The objective of this is to avoid lowering the difficulty level of the examinations while seeking to reduce the range of the failure rate. In our material, this would have been achieved with a ‘modified Cohen’ method and a K value of 0.70. This sets the limit for a pass grade at 70 % of the point score of the students in the 90th percentile.

It is difficult to assess the quality of a standard-setting method, since it is hard to tell where the ‘true’ limit to a pass grade should be for each individual examination. Cohen’s methods have the advantage of being predictable for the students, since they will know that they never need a higher percentage of correct answers than the stated K value (provided that those in the 90th or 95th percentile score perfectly). They will also know that the method corrects for the degree of difficulty of the test and that the test is not subject to the discretionary judgement of an examination committee. Let us assume that the faculty decides to use the Cohen method with a K = 0.70. Those who achieve 70 % of the scores of the students in the 90th percentile will pass, those who score lower will fail.

Another advantage of Cohen’s methods when compared to other relative methods is that they do not produce a fixed failure rate. We feel that it would be problematic to introduce a standard-setting method that lowers the existing 65 % absolute limit for a pass grade. Although the failure rate varies, the number of medical students who fail annually is nevertheless small compared to other study programmes (5, 6).

Absolute methods that involve expert panels are probably the solution most likely to produce the ‘true’ limit for a pass grade on a medical examination 2, 3). This solution is used in many places, including the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) (8). In practice, however, it would be hard to implement for all examinations in each medical faculty. Based on our findings, we believe that a 65 % absolute limit for a pass grade can be defended for as long as the failure rate remains as low as today. A standard-setting method needs to have credibility. If the variation in the failure range from one year to the next becomes excessive when testing a homogenous group of students assessed according to the admission criteria for medical studies, the examination loses its credibility (4). Cohen’s methods should be used in medical schools with an extremely high failure rate, or where there are major variations in the failure rate for the same examination in the course of study. We believe that the methods could be suitable at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) if the failure rate for examinations deviates considerably from what is common now.