Acute otitis media is a common reason for young children visiting a doctor or emergency primary health care unit (1). It is also a common reason for prescribing antibiotics for young children. If preventive measures were able to reduce the incidence of otitis, the use of antibiotics among children would also be reduced.

Otitis is often caused by viruses, while pneumococci are the most common bacterial cause (2). Pneumococcal vaccines have been developed which have been shown to be effective against otitis caused by the serotypes found in the vaccine (3). Since the introduction of such pneumococcal vaccines in the USA, a downward trend has been observed in the incidence of otitis (4).

In Norway, the pneumococcal vaccine was introduced as part of the Childhood Immunisation Programme in 2006; first in the form of a seven-valent vaccine (PKV7), then a thirteen-valent vaccine (PKV13) from April 2011. The vaccine is given at the age of three, five and twelve months. In recent years, vaccination coverage has been 91–95 % (5). A gradually increasing percentage of 0–5-year-olds were therefore vaccinated between 2006 and 2011. Since 2011, vaccination coverage in this group of children has stabilised at over 90 %.

The purpose of this study was to map the annual consultation rate for children aged 0–5 attending an emergency primary health care centre in the period 2006–18. Another objective was to assess whether changes in the consultation rate may be related to the introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine.

Material and method

The material consists of data from all electronic reimbursement claims from emergency primary health care doctors in the period 2006–18, which had previously been used to compile the annual statistics for the emergency primary health care services (Årsstatistikk fra legevakt) (1). Anonymised data files were obtained from the Norwegian Health Economics Administration/Control and Payment of Reimbursement to Health Service Providers (KUHR).

Consultations and home visits (tariff codes 2ad, 2ak, 2fk, 11ad or 11ak, herein referred to as consultations) were recorded for children aged 0–5 years. Consultations due to acute otitis media are characterised by ICPC-2 diagnostic code H71.

Vaccination coverage was obtained from the Norwegian Immunisation Registry (SYSVAK) (5). This states the annual rate of two-year-olds who have been fully vaccinated against pneumococcal disease. Such figures are available from 2008 and largely include all children vaccinated in 2006. In this study, I have chosen to use the year the child was vaccinated, whereby vaccination data are given for the years 2006–16. Consequently, vaccination coverage will be somewhat overestimated, since many children received their vaccines over two consecutive years. Since pneumococcal vaccination was introduced in 2006, the first five cohorts will have been vaccinated in 2011.

The annual statistics for the emergency primary health care service were assessed by the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration’s data protection officer and by the Data Protection Official for Research (1). Because it is impossible to identify individuals on the basis of the material, be it directly or indirectly, the project is not subject to the notification requirements imposed by the Norwegian Personal Data Act.

Because the material comprises all the electronic reimbursement claims rather than a sample, the differences demonstrated are real and not encumbered by statistical uncertainty. The data are therefore presented without confidence intervals, and no statistical tests have been conducted.

Results

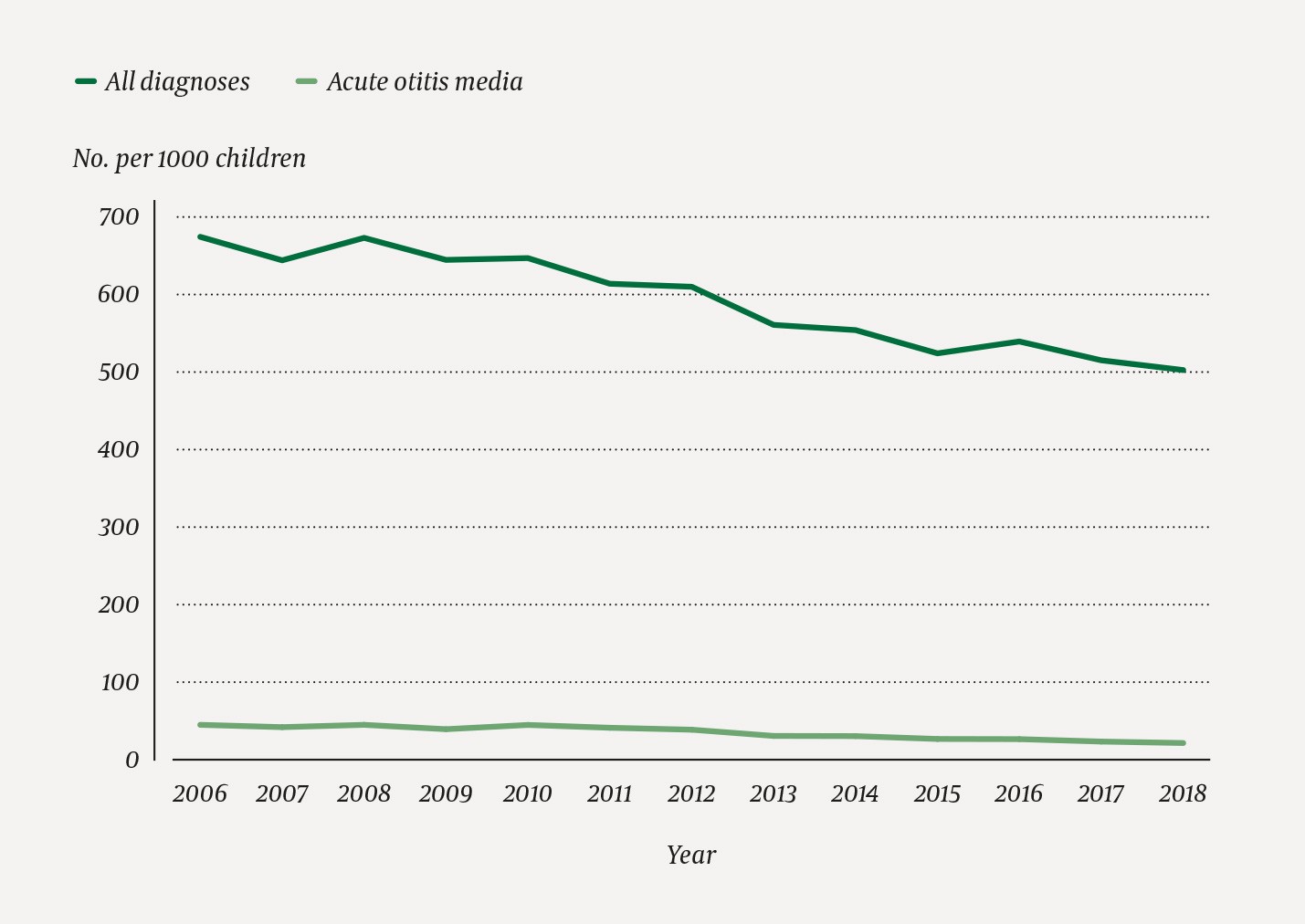

An overview of all consultations for children aged 0–5 years is shown in Figure 1. The consultation rate fell from 674 per 1000 inhabitants in 2006 to 502 in 2018; a relative reduction of 26 %.

Figure 1 Consultation rates at emergency primary health care units for children aged 0–5 years in the period 2006–18.

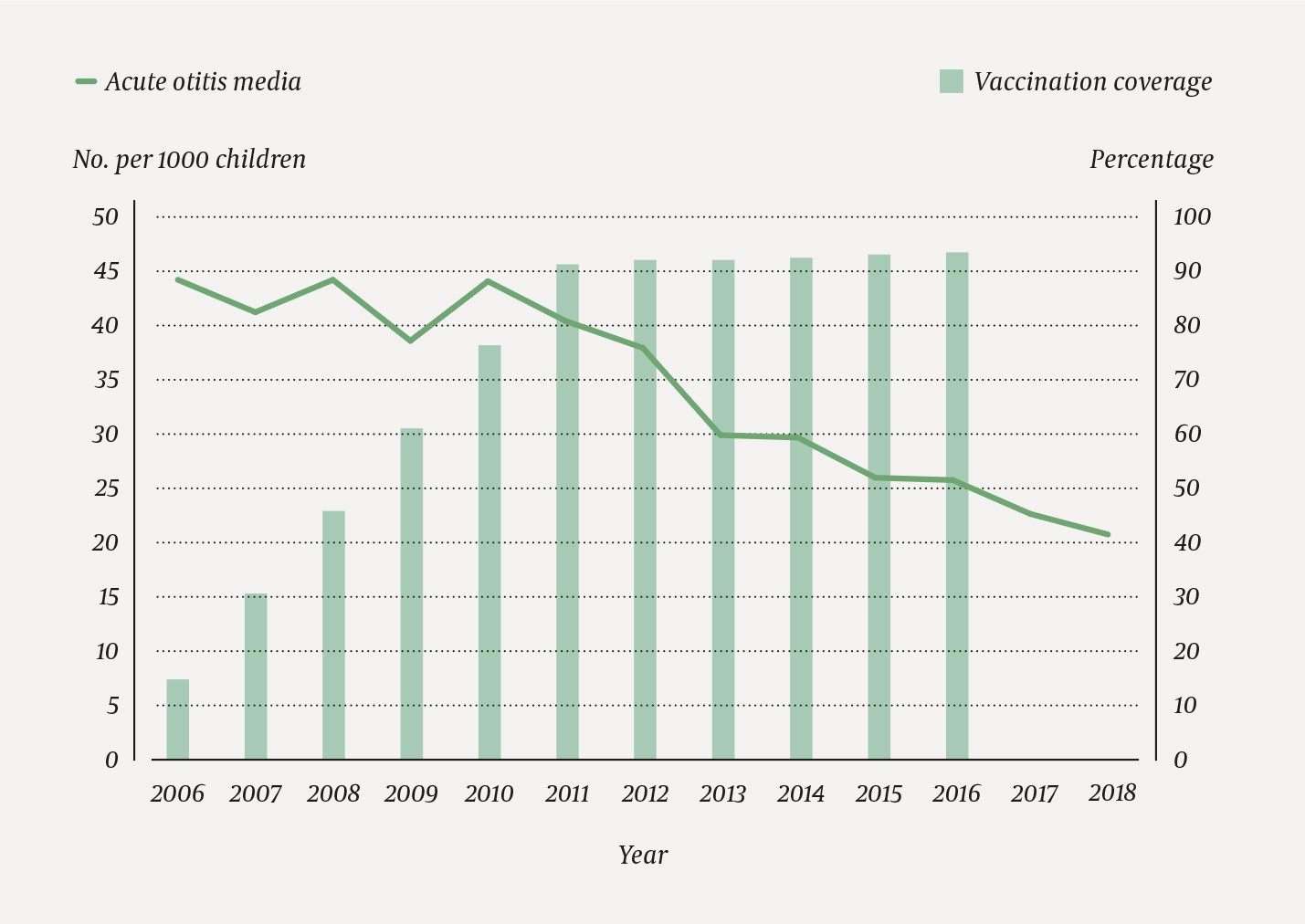

Figure 2 shows corresponding consultation rates for otitis. Here, the rate has decreased from 44 per 1000 inhabitants in 2006 to 21 in 2018; a relative reduction of 52 %. This entire reduction occurred after 2010. Figure 2 also shows the vaccination coverage in the relevant group of children, increasing gradually from 15 % in 2006 to over 90 % from 2011 onwards.

Figure 2 Consultation rates at the emergency primary health care units for children aged 0–5 years in the period 2006–18 with the diagnosis acute otitis media. The columns represent the percentage of the entire group that was vaccinated against pneumococci. During this period, there was an average of 364 100 children in the age group 0–5 years.

Discussion

The study shows that the consultation rate for young children at primary health care units has been decreasing over time. However, the reduction in visits due to otitis has been twice that of other diagnoses. Furthermore, it is clear that there was a stronger reduction in visits due to otitis when the group of children in question was fully vaccinated against pneumococcal disease.

Calculated as a percentage of all ear-related diagnoses by general practitioners, there are indications that seeking medical attention due to otitis has been declining ever since the mid-1990s (2, 6). Children are less likely to be exposed to passive smoking than before, which may have contributed to the reduced incidence of otitis (7). There has been a growing focus on the use of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance, and it is possible that parents are increasingly adopting a wait-and-see approach before contacting a doctor. Another possible explanation for the reduction in the use of the emergency primary health care services may be the more frequent use of private medical services. GP consultations for the reference age group have not increased in recent years (8), but it is still possible that a larger proportion of otitis patients visit a GP instead of going to an emergency primary health care unit.

All of these alternative explanations may go some way to explaining the reduction in the use of emergency primary health care units, but they do not explain the shifting trend in the incidence of otitis as from 2011 (Figure 2). Vaccination coverage may be a possible explanation here. However, the sharp decline in consultations due to otitis continues in the years after vaccination coverage in the age group 0–5 years has stabilised at over 90 %. This may be related to additional protection as a result of herd immunity when older children are also immunised.

A published Norwegian study examined the relationship between pneumococcal vaccination and otitis in young children (9). This study included children who took part in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study (MoBa), and the frequency of otitis was based on information provided by the mothers. The study found that fully vaccinated children aged 12–18 months had a 14 % lower risk of otitis than children who had not been vaccinated.

At the emergency primary health care units, it is the doctor who makes the diagnosis, and it must be assumed that this is a more valid diagnosis than retrospective information based on the mother’s memory. A recently published article from Norwegian general practice indicates that diagnoses based on reimbursement claims have a workable validity (10).

Conclusion

Since 2010, consultations at emergency primary health care units due to otitis in young children have more than halved. This coincides with the fact that the group in question was fully vaccinated against pneumococcal disease as from 2011. However, we cannot conclude that there is a confirmed causal relationship.