Social, demographic, economic and cultural patterns of cigarette smoking indicate that the smoking epidemic is on the verge of an historic decline in Norway. The typical smoker is middle-aged and divorced, has little education, lives far north and has manual work or no work (1), and clearly – a low potential as a trendsetter. The population has much knowledge about health risks and there is an increasing normative pressure to be a non-smoker. On this background, a renaissance for cigarette smoking is rather unlikely. Our descents will most probably regard the approximate 100-year period with massive cigarette smoking as an unfortunate parenthesis in the history of mankind. An epidemic’s decline requires some retrospective consideration. This article documents the smoking epidemic’s rise and fall in the 20th century in a gender perspective.

Material and method

Tobacco supply sources

The Norwegian Directorate of Customs and Excise keep records of tobacco sales within Norway, and annual sales are available from 1927. While sales of tobacco for hand-rolled cigarettes has been reported by weight, that of machine-made cigarettes has been by number of cigarettes. One machine-made cigarette contains 1 g of tobacco and sales of these have been calculated and presented by weight in this article. Border trading with the Swedes and tobacco import associated with travelling, are increasing supply sources for which the magnitude has been estimated previously (2). To correct for population growth, the total annual consumption was divided by the number of persons above 15 years of age living in Norway.

Prevalence of smokers and number of cigarettes per day

Information on proportions of smokers and consumption of cigarettes was retrieved from Statistics Norway (annual investigations of smoking habits) for the period 1973 – 2007. The annual investigations have included representative samples of 1 300 – 3 000 persons; the response rate has been 63 – 80 % with a decreasing tendency over time (3).

For the years 1956, 57, 58, 60, 64, 66, 70 and 74, data on smoking prevalence were retrieved from table reports prepared by TNS Gallup (Norway’s largest marked research company). The number of respondents was 789 – 1 054; response rate was not given, but tabulations of the samples showed good representativeness for demographic variables at every time-point (4). Supplementary data for the period 1954 – 73 were retrieved from Nielsen Norway’s 6-month investigations in samples of 6 000 – 10 000 persons (5). From 1960, these table reports also had information on average daily cigarette consumption.

For the period before 1954, data on proportion of smokers and cigarette consumption were retrieved from a representative study made by the Cancer Registry in 1964/65. In this study 7 537 women and 6 708 men (born in the period 1893 – 1927) answered questions that made it possible to reconstruct smoking status and consumption throughout life. The response rate was 82 %. Rønneberg and collaborators had previously used several of the data sets that we have used, and we refer to them for a more detailed description of the data and for the calculation method (6).

When several investigations were made during a year, an average was used to make the estimates more robust. For years with lack of information on daily cigarette consumption, data based on interpolation were added. To decrease the effect of random fluctuations in the material, both proportion of smokers and daily consumption were expressed by moving averages over three-year periods.

Gender-specific consumption

Information on men and women aged 15 – 74 years and living in Norway was retrieved from Statistics Norway for each year in the period 1927 – 2007. This information was used to calculate the number of smokers within each sex for each calendar year in the entire 80-year period. The smoking population’s accumulated daily consumption was then calculated for each year by multiplying the number of smokers with self-reported cigarette consumption (for men and women) in the year in question. We could then express percentual proportion of consumption for each sex in a way that took differences between men and women, both regarding smoking proportion and consumption, into account. By multiplying this proportion with total consumption for specific years we achieved gender-specific tobacco consumption.

Results

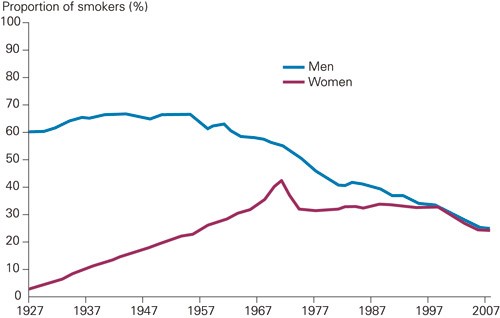

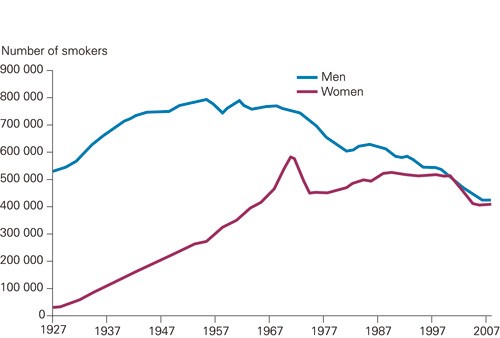

In the end of the 1920s, smoking was much more prevalent among men than women (fig 1). Up to about 1960 around 65 % of men smoked, as compared with 25 % after the year 2000. From a low level of about 5 % around the year 1930 smoking among women increased to about 35 % in 1975 (fig 1). The increase was especially steep in the period 1965 – 75, after a short decline. Up to about 2000 the prevalence of smokers among women was slightly above 30 % and quite stable. Smoking among women has thereafter declined with the same rate as that for men (fig 1). However, due to population growth, the number of women who smoke has not been reduced with more than about 150 000 since the culmination in 1975. The number of male smokers has been halved (reduced by 400 000) since the culmination in 1960 (800 000 smokers) (fig 2).

Figure 1 Proportion of smokers among men and women living in Norway in the period 1927 – 2007 (three-year averages)

Figure 2 Number of smokers among men and women in the period 1927 – 2007

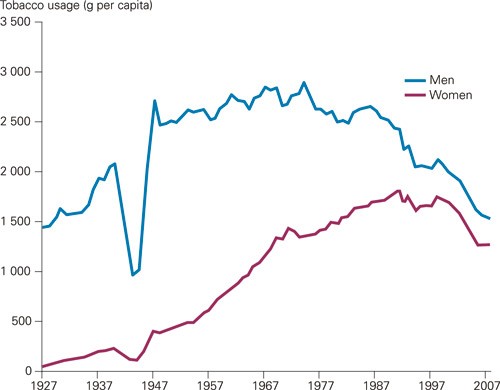

Men have reported higher daily cigarette consumption than women in the entire period. This difference explains why men continued to consume more tobacco than women, despite of a sex convergence in number of smokers after 1995 (fig 3). In 1930, men consumed about 95 % of all cigarettes, while in the last decades they have consumed about 55 % of the total quantity.

Figure 3 Amount of tobacco consumed annually by men and women over 15 years in the period 1927 – 2007

The annual consumption of cigarettes per man over 15 years culminated at 2.8 kg in the middle of the 1970s. About 30 years later the consumption was down to 1.5 kg, about the same as in the end of the 1920s. Around 1990 a culmination at 1.8 kg was observed for women. Thereafter the consumption decreased to about 1.3 kg per adult women in 2007.

Discussion

Massive tobacco consumption started in Norway at the same time as the tobacco industry was automated about 100 years ago. Our investigation shows that men must have consumed more than 70 % of all cigarettes smoked in Norway since 1927. In an epidemiological perspective, men have had a longer and more intense exposure to cigarettes than women.

Increase in cigarette consumption

Several publications have explained the changes in smoking patterns in Norway in detail (7, 8) from a social science perspective. They have emphasized that increases in the first half of the 1900s coincided with an extensive commercial pressure that linked cigarette smoking with modernism, a refined lifestyle and elegance. Key communicators at the time were men in the urban middle class – effective role models that contributed to introducing tobacco to other population groups. Female smokers were generally rare, but rather common in socially marginalized groups, such as bohemians and prostitutes. After the Second World War, the authorities gave tobacco status as a necessity and they supplied it to people through the Marshall help. Smoking was deeply rooted in social life; it was common among doctors and top athletics and was visualized through TV programmes, films, newspaper pictures and commercials. We must assume that doctors – as role models – sent quite strong and positive signals about smoking to the general public. In 1952, 74 % of male Norwegian doctors and 44 % of female doctors smoked (9). The country’s social minister participated in commercials for cigarettes in the 1950s.

The pro-tobacco social climate in the 1950s and 60s made it difficult to disseminate information on adverse health effects of smoking in an effective way. For a long time warnings were communicated by moral entrepreneurs who many considered were on an ethical crusade and therefore had reduced credibility (10). Newspapers and textbooks contained little information to counteract the massive commercials that glorified smoking (11). The commercials became more aggressive from the time final evidence on health risks of smoking became available (12). Up to 1970, doctors and authorities had a very low profile and did not inform about dangers of tobacco nor engage themselves in preventive work. The State Information Service was responsible for the first publicly financed information campaign, which was launched in 1975.

Reduced cigarette consumption

The decline in tobacco consumption among men coincided with implementation of a nationwide tobacco legislation. From 1975 there was a total ban on all commercials for tobacco, introduction of health warnings on cigarette and tobacco packs and a 16-year age limit for buying and selling tobacco. The law was later expanded with paragraphs that protected people against passive smoking on work places and means of transportation (1989), and in places where food was served (2004); new nicotine products were banned (1989), more (1984) and larger (2003) health warnings and a higher age limit for buying and selling tobacco was set at 18 years (1995). The real price of tobacco increased several times after 1975, systematic preventive measures were instigated and campaign activity was intensified.

The authorities’ initiatives have contributed to reducing smoking, but the reductions are caused by many factors outside of the authorities’ direct control; such as smoking’s changed symbolic content, user groups’ lowered status, launching of nicotine-containing drugs to quit smoking and the renaissance for snuff (7).

Delays in changes among women

As shown in figure 1 women started to smoke later than men. Rønneberg and collaborators (6) found that women consumed tobacco later in life than men. This sex difference must be interpreted in light of the restrictive norms for female smokers which prevented the industry from tailoring market campaigns specifically towards women. As a group, women lacked typical innovative traits, such as a long education and cosmopolitan orientation. They were more religious and administrators of the private family sphere. Women participated less in societal areas that could be considered secular, norm weakening and recruiting for smoking (7, 8).

The increase in women’s smoking was naturally associated with more liberal norms and the subsequent increase in marketing directed towards women (12). Periods with war and social and economic liability had contributed to less stringent norms. More women also took paid work and became part of working environments where smoking occurred and where they had not been before.

The authorities’ anti-smoking campaigns came earlier in the development of womens’ smoking habits than that for men. This has probably contributed to women’s lower level of tobacco consumption at the time of culmination than that for men.

Figure 1 shows that the decline of women’s tobacco consumption started later than that for men. This was caused by a cohort effect. In the 1970s there were few elderly female smokers, caused by the fact that it was uncommon for this generation to smoke when they were young (in the 1920s and 30s) (6). As new generations of women – who have grown up in a more smoking-positive atmosphere in the 1950s – have become old, the effect of reduced consumption among middle-aged women has diminished. However, the cohort effect decreased towards the turn of the century, and afterwards women have reduced their tobacco consumption to the same extent as men.

Data deficiencies

Mapping of cigarette consumption (for both sexes) over a period of 80 years is associated with measurement problems for accuracy of total consumption (recorded + unrecorded), and for those data (on prevalence and intensity) that are included in calculations of gender-specific proportions of total consumption. Firstly, the tobacco industry’s estimates of unrecorded tobacco consumption after 1980 may be too high, because they wish to put pressure on politicians to reduce the tobacco tax. However, results from representative questionnaire surveys on supply sources among Norwegian smokers have corresponded well with estimates from the industry (2). Secondly, no estimates of unrecorded tobacco consumption are available from the Second World War, but according to anecdotal sources there was an extensive unrecorded home production of tobacco. Tobacco consumption in 1940 – 45 was probably substantially higher than that shown by our data. Thirdly, the weight of tobacco in machine-made cigarettes has decreased somewhat from the 1980s, and recalculation with the presumption that 1 cigarette corresponds to 1 g of tobacco will result in estimates that are too high. Fourthly, we do not have data that make it possible to estimate the proportion of rolled tobacco smoked in pipes. Pipe smoking was common among men up to the 1970s. Also, we have not made assumptions on tobacco originating from smuggling, but previous calculations have shown that smuggled tobacco only contributes modestly to the total consumption (2).

Interpolation and reconstruction has been necessary because some annual observations (on prevalence of smokers and intensity of consumption) were missing early in the period. Some point observations are therefore less reliable in the time period 1927 – 54 than in later periods. We also assume that under-reporting of smoking status has increased in studies, because smoking now deviates more from the accepted norms. Despite of these measurement problems we believe that the overview is representative for the actual development of cigarette consumption for both men and women.

Conclusion

Cigarette smoking has been common in all layers of society for about 100 years, but seems to be phasing out. Men have been responsible for about 70 % of the total tobacco consumption during the epidemic’s last 80 years. Smoking among women increased later than that among men, and consumption culminated on a much lower level.